Chapter-16

The following day, the marriage between Mr Rochester and Jane Eyre was to take place in church. Jane was dressed beautifully by Sophie, the maid-servant at Thornfield Hall. Mr Rochester ordered one of his servants to go to church and see whether Mr Wood, the clergymen of church, was ready.

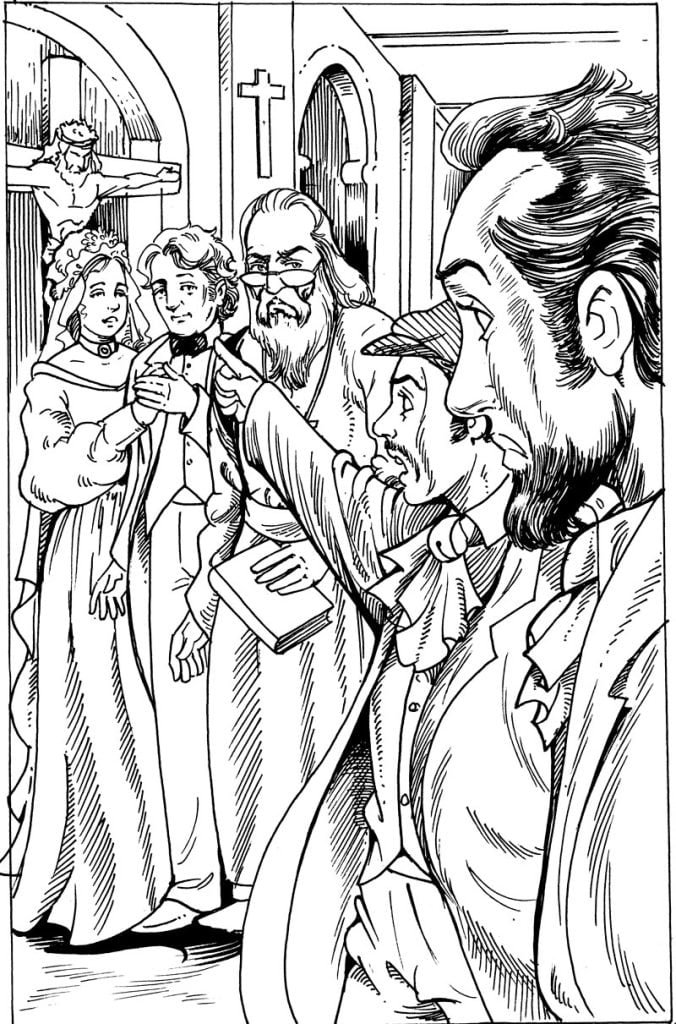

When everything was ready, both Mr Rochester and Jane set out. Jane had also informed her uncle, John Eyre, about her marriage. Reaching church both greeted the clergyman. No guests were invited. It was a simple ceremony.

The clergyman said to Mr Rochester, “Do you accept Jane as your married wife?”

Before Mr Rochester could utter anything, a stranger appeared on the scene and shouted from a distance, “Mr Wood! this marriage can’t take place. For your kind information, Mr Rochester is already married and his wife is still alive.”

Hearing the words of the stranger, Jane felt as if ground had slipped from under her feet. She was in a state of shock. Mr Rochester drew Jane close to himself and said the stranger, “Who are you? Do you have any proof of my marriage?”

The strange replied, “Mr Rochester! I am Briggs, a solicitor by profession. I have a letter with me. It mentions that you married Bertha Mason of Jamaica, on the 20th of October, fifteen years ago. There is also a record of your marriage in the church-register.” Saying these words, Mr Briggs handed the letter across to Mr Wood who went through the letter.

Mr Rochester grew impatient. He said to Briggs, “Do you have a witness to my marriage?”

Soon, Mr Briggs brought Mr Mason in. He was the brother of Bertha Mason. Mr Wood enquired of Mr Mason about the marriage. Mr Mason told him that his sister was still alive.

Mr Wood declared thus, “This marriage can’t take place today.” Hearing the words of Mr Wood, Mr Rochester flew into a rage and said, “Yes, I married Bertha Mason. But she is mad. Her mother was mad. She was a drunkard too. She is under care of Grace Poole.”

All of them except Mr Wood left the church and headed for Thornfield Hall. Reaching there Mr Rochester followed by others walked into the room of Grace Poole. No sooner did he step into the room than Bertha Mason, the lunatic wife of Mr Rochester, grabbed his throat and bit his cheek. Somehow, Mr Rochester and Grace Poole brought her under control and tied her to a chair.

Then, Mr Briggs moved towards Jane Eyre and said, “Jane! when you informed your uncle John Eyre of your marriage, Mr Mason happened to be there. He told your uncle that Mr Rochester was already married. You uncle felt unhappy and wrote to me to intervene and withhold the marriage. Now, my duty is over. I wish you all the best.” Saying these words, both Mr Briggs and Mr Mason departed from there. Mr Rochester, too, went back to his room. Jane was left alone there in the room of Grace Poole.

After some time, Jane, too, retired to her room. She took off her wedding dress. She was depressed a lot. She was a solitary girl again with bleak prospects. She was moving to and fro in her room. Her limbs felt weak. She decided to leave Thornfield Hall for ever. All of a sudden, she fainted and was about to fall down to the ground when Mr Rochester stepped in. He held her tightly in his hands and made her sit comfortably. He gave her water to drink. Jane Eyre came to her senses after some moments. Then, she said to Mr Rochester, “Sir! why have you come to me now? Everything is perished. All my hopes have been dashed to ground.”

Mr Rochester replied, “Dear! I never meant to hurt your feelings. I know you will never forgive me.” There was deep remorse in his eyes. He still loved Jane who forgave him at once. Mr Rochester tried to kiss Jane who turned aside.

Jane said to Mr Rochester, “Sir! everything has changed. I too must change. I am leaving Thornfield Hall for good.”

Mr Rochester spoke out, “O Jane! you shun me and live here as Adele’s governess. If you really want to depart from here then take little Adele with you. Who will take care of her in your absence?”

Jane replied, “Sir! how can she share my solitude? I have no house to live in.”

Mr Rochester said, “Dear Jane! I still love you. My marriage with Bertha Mason was purely accidental. I was angry with my father who was partial to my elder brother Rowland. He left the entire estate to him and sent me to the West Indies to earn my living. I was forced by my father to do business in partnership with Mr Mason. My father was very wealthy. After a few months, my father told me to marry Bertha Mason, the daughter of Mr Mason. My father was to get thirty thousand pounds as marriage settlement. My father said nothing about her money. But he told me that Miss Mason was the boast of spanish town for her beauty. This was no lie. I found her a fine woman, in the style of Blanche Ingram : tall, dark and majestic. Her family wished to secure me because I was of a good race; and so did she. They showed her to me in parties, splendidly dressed. I seldom saw her alone, and had very little private conversaton with her. She flattered me, and lavishly displayed for my pleasure her charms and accomplishments. All the men in her circle seemed to admire her and envy me. I was dazzled, stimulated; my senses were excited; and being ignorant, raw and inexperienced, I thought I loved her. There is no folly so besotted that the idiotic rivalries of society, the prurience, the rashness, the blindness of youth, will not hurry a man to its commission. Her relatives encouraged me; competitors piqued me; she allured me : a marriage was achieved almost before I knew where I was. Oh! I have no respect for myself when I think of that act. An agony of inward contempt masters me. I never loved; I never esteemed, I didn’t even know her. I was not sure of the existence of one virtue in her nature. I had marked neither modesty, nor benevolence, nor candour, nor refinement in her mind or manners. At last, I married her—gross, grovelling, mole-eyed blockhead that I was. With less sin I might have. But let me remember to whom I am speaking.”

“I had never seen my bride’s mother. I understood she was dead. The honeymoon over, I learnt my mistake. She was only mad, and shut up in a lunatic asylum. There was a younger brother too—a complete dumb idiot. The elder one, whom you have seen (and whom I can’t hate, while I abhor all his kindred, because he has some grains of affection in his feeble mind, shown in the continued interest he takes in his wretched sister, and also in a dog-like attachment he once bore me), will probably be in the same state one day. My father and my brother Rowland knew all this; but they thought only of the thirty thousand pounds, and joined in the plot against me. These were vile discoveries; but except for the treachery of concealment, I should have made them no subject of reproach to my wife, even when I found her nature wholly alien to mine, her tastes obnoxious to me, her cast of mind common, low, narrow and singularly incapable of being led to anything higher, expanded to anything larger—when I found that I couldn’t pass a single evening, nor even a single hour of the day with her in comfort; that kindly conversation could not be sustained between us because whatever topic I started, immediately, received from her a turn at once coarse and trite, perverse and inbecile. I perceived that I should never have a quiet or settled household because no servant would bear the continued outbreaks of her violent and unreasonable temper or the vexations of her absurd, contradictory, exacting orders—even then I restrained myself. I eschewed upbraiding. I curtailed remonstrance; I tried to devour my repentance and disgust in secret; I repressed the deep antipathy I felt. Jane! I will not trouble you with abominable details. Some strong words shall express what I have to say. I lived with that woman upstairs four years. Before that time, she had tried me indeed. Her character ripened and developed with frightful rapidity. Her vices sprang up fast and rank. They were so strong—only cruelty could check them. I would not use cruelty. What a pigmy intellect she had and what giant propensities! How fearful were the curses those propensities entailed on me! Bertha Mason, the true daughter of an infamous mother, dragged me through all the hideous and degrading agonies which must attend a man bound to a wife at once intemperate and unchaste.”

“My brother in the interval was dead. At the end of the four years my father died too. I was rich enough now—yet poor to hideous indigence : a nature the most gross, impure, depraved I ever saw, was associated with mine, and called by the law and by society a part of me. I couldn’t rid myself of it by any legal proceedings, for the doctors now discovered that my wife was mad—her excesses had prematurely developed the germs of insanity. Jane! you don’t like my narrative; you look almost sick—shall I defer the rest to another day?”

“No Sir; finish it now. I pity you…I do earnestly pity you,” said Jane.

“Pity, Jane, from some people is a noxious and insulting sort of tribute, which one is justified in hurling back in the teeth of those who offer it; but that is the sort of pity native to callous, selfish hearts; it is a hybrid, egotistical pain at hearing of woes, crossed with ignorant contempt for those who have endured them. But that is not your pity, Jane; it is not the feeling of which your whole face is full of this moment—with which your eyes are now almost overflowing—with which you heart is heaving—with which you hand is trembling in mine. Your pity, my darling, is the suffering mother of love. Its anguish is the very natal pang of the divine passion. I accept it, Jane; let the daughter have free advent—my arms wait to receive her.”

“Now, sir, proceed; what did you do when you found she was mad?” asked Jane.

“Jane, I approached the verge of despair; a remnant of self-respect was all that intervened between me and the gulf. In the eyes of the world, I was doubtless covered with grimy dishonour; but I resolved to be clean in my own sight—and to the last I repudiated the contamination of her crimes and wrenched myself from connection with her mental defects. Still, society associated my name and person with hers; I yet saw her and heard her daily—something of her breath mixed with the air I breathed. Besides, I remembered I had once been her husband—that recollection was then, and is now, inexpressibly odious to me. Moreover, I knew that while she lived I could never be the husband of another and better wife. Though five years my senior (her family and her father had lied to me even in the particular of her age), she was likely to live as long as I, being as robust in frame as she was infirm in mind. At the age of twenty-six, I was hopeless.”

“One night I had been awakened by her yells. Since the medical man had pronounced her mad, she had, of course, been shut up. It was a fiery west Indian night; one of the descriptions that frequently precedes the hurricanes of those climates. Being unable to sleep in bed, I got up and opened the window. The air was like sulphur-steam. I could find no refreshment anywhere. Mosquitoes came buzzing in and hummed sullenly round the room. The sea which I could hear from thence, rushed dull like an earthquake. Black clouds were casting up over it. The moon was setting in the waves, broad and red, like a hot cannon ball. She threw her last bloody glance over a world quievering with the ferment of tempest.”

“With the passage of time, Bertha Mason turned out to be a wild creature. Her condition went from bad to worse. Finally, she became as mad as her mother. I never loved her. I brought her to Thornfield and appointed Grace Poole to look after her. Nobody knew about my marriage with her. I became a wanderer. I was always on the look-out for an intelligent girl with whom I could spend the rest of my life. Then, one day, I met you. The rest is history.”

Hearing of the pathetic tale of Mr Rochester there were tears in the eyes of Jane Eyre. In the next moment, she got down to the reality. She told Mr Rochester to go away as she had to set out early next morning. Mr Rochester returned to his room, dejected and unhappy.

Jane packed her belongings throughout the whole night. Next morning, She was ready to depart. She bade farewell to every member of Thornfield Hall. She kissed Adele a lot. Without saying anything to Mr Rochester she set out. She had a parcel in her hand. She was nowhere to go. She took a road which she had never travelled. On her way, she fainted a little bit.

All of a sudden, she saw a carriage approaching her. The carriage stopped near her. She gave twenty shillings to the driver and got in. She was left at a place called Whitcross which was neither a town nor a village. The closest village was ten miles away. Jane could not walk. So, she decided to spend the night on the road. She ate the bread which she had with her. After resting for some time, she walked towards the village. She was terribly hungry but was too ashamed to ask anybody for something to eat. She went to a shop on the way but had no money to buy food as she had left her parcel in the carriage. She was frustrated a lot. As she entered the village, she knocked at a door. A lady appeared there and said, “What do you want?”

Jane replied, “I want some job. I can do your household chores.”

The lady retorted, “Sorry; we don’t keep a servant.” Walking on and on Jane went across a field and reached a church. She thought it wise to enter the church and apply to the clergyman for employment. When she entered the church, he was told that the clergyman was away for a fortnight. Jane felt depressed. She decided to end her life. She moved towards a hill. There was a house beside the hill. A candle was flickering in the house. There was some glitter of hope in the eyes of Jane. She, at once, went up to the house and knocked at its door. A lady appeared there and enquired of Jane about her visit. Jane said humbly, “I seek shelter in your house.”

The lady retorted, “Go away; we don’t have any job. As the lady tried to shut the door, Jane said, “Please let me meet your mistress. I am in dire straits. Don’t shut the door for God’s sake.”

The lady did not pay any heed to what Jane had said. She slammed the door into the face of Jane and bolted in from inside. Jane was all alone. She was helpless. She was dead tired. She groaned and wept in anguish. Soon, she fainted at the door.

After some time a hand patted the back of Jane. A man was standing there near Jane. He sprinkled water on Jane who came to her senses. He knocked at the door loudly. He took Jane inside and made her sit comfortably. His name was St John. He lived there with his two sisters—Diana and Mary and their maid, Hannah, who had slammed the door to Jane’s face. He ordered Hannah to fetch some bread and milk for Jane.

After Jane had taken bread and milk, St John said to her, “O young lady! what is your good name?” Jane told him that her name was Jane Elliot. She did so to avoid being found out. Both the sisters of St John took great care of Jane who thanked God and slept pleasantly waiting for the following day.