Chapter 1

In the western part of England lived a gentleman of great fortune, whose name was Merton. He had a large estate in the Island of Jamaica, where he had passed the greater part of his life, and was master of many servants, who cultivated sugar and other valuable things for his advantage. He had only one son, of whom he was excessively fond; and to educate this child properly was the reason of his determination to stay some years in England. Tommy Merton, who, at the time he came from Jamaica, was only six years old, was naturally a very good-tempered boy, but unfortunately had been spoiled by too much indulgence.

While he lived in Jamaica, he had several black servants to wait upon him, who were forbidden upon any account to contradict him. If he walked, there always went two negroes with him; one of whom carried a large umbrella to keep the sun from him, and the other was to carry him in his arms whenever he was tired. Besides this, he was always dressed in silk or laced clothes, and had a fine gilded carriage, which was borne upon men’s shoulders, in which he made visits to his play-fellows. His mother was so excessively fond of him that she gave him everything he cried for, and would never let him learn to read because he complained that it made his head ache.

The consequence of this was, that, though Master Merton had everything he wanted, he became very fretful and unhappy. Sometimes he ate sweetmeats till he made himself sick, and then he suffered a great deal of pain, because he would not take bitter physic to make him well. Sometimes he cried for things that it was impossible to give him, and then, as he had never been used to be contradicted, it was many hours before he could be pacified. When any company came to dine at the house, he was always to be helped first, and to have the most delicate parts of the meat, otherwise he would make such a noise as disturbed the whole company. When his father and mother were sitting at the tea-table with their friends, instead of waiting till they were at leisure to attend him, he would scramble upon the table, seize the cake and bread and butter, and frequently overset the tea-cups. By these pranks he not only made himself disagreeable to everybody else, but often met with very dangerous accidents. Frequently did he cut himself with knives, at other times throw heavy things upon his head, and once he narrowly escaped being scalded to death by a kettle of boiling water. He was also so delicately brought up, that he was perpetually ill; the least wind or rain gave him a cold, and the least sun was sure to throw him into a fever. Instead of playing about, and jumping, and running like other children, he was taught to sit still for fear of spoiling his clothes, and to stay in the house for fear of injuring his complexion. By this kind of education, when Master Merton came over to England he could neither write nor read, nor cipher; he could use none of his limbs with ease, nor bear any degree of fatigue; but he was very proud, fretful, and impatient.

Very near to Mr Merton’s seat lived a plain, honest farmer, whose name was Sandford. This man had, like Mr Merton, an only son, not much older than Master Merton, whose name was Harry. Harry, as he had been always accustomed to run about in the fields, to follow the labourers while they were ploughing, and to drive the sheep to their pasture, was active, strong, hardy, and fresh-coloured. He was neither so fair, nor so delicately shaped as Master Merton; but he had an honest good-natured countenance, which made everybody love him; was never out of humour, and took the greatest pleasure in obliging everybody. If little Harry saw a poor wretch who wanted victuals, while he was eating his dinner, he was sure to give him half, and sometimes the whole: nay, so very good-natured was he to everything, that he would never go into the fields to take the eggs of poor birds, or their young ones, nor practise any other kind of sport which gave pain to poor animals, who are as capable of feeling as we ourselves, though they have no words to express their sufferings. Once, indeed, Harry was caught twirling a cock-chafer round, which he had fastened by a crooked pin to a long piece of thread: but then this was through ignorance and want of thought; for, as soon as his father told him that the poor helpless insect felt as much, or more than he would do, were a knife thrust through his hand, he burst into tears, and took the poor animal home, where he fed him during a fortnight upon fresh leaves; and when he was perfectly recovered, turned him out to enjoy liberty and fresh air. Ever since that time, Harry was so careful and considerate, that he would step out of the way for fear of hurting a worm, and employed himself in doing kind offices to all the animals in the neighbourhood. He used to stroke the horses as they were at work, and fill his pockets with acorns for the pigs; if he walked in the fields, he was sure to gather green boughs for the sheep, who were so fond of him that they followed him wherever he went. In the winter time, when the ground was covered with frost and snow, and the poor little birds could get at no food, he would often go supperless to bed, that he might feed the robin-redbreasts; even toads, and frogs, and spiders, and such kinds of disagreeable animals, which most people destroy wherever they find them, were perfectly safe with Harry; he used to say, they had a right to live as well as we, and that it was cruel and unjust to kill creatures, only because we did not like them.

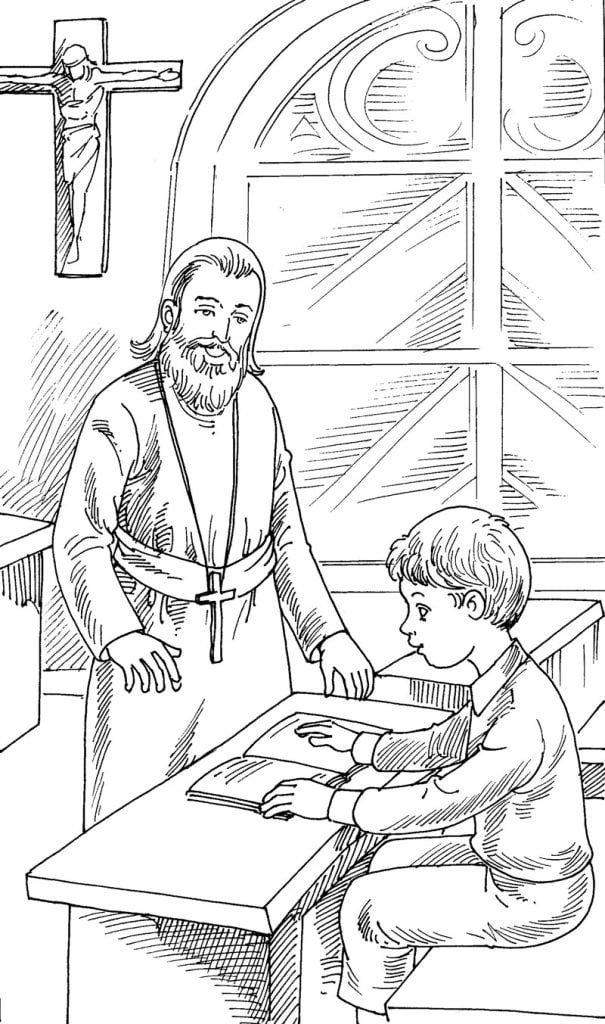

These sentiments made little Harry a great favourite with everybody, particularly with the clergyman of the parish, who became so fond of him that he taught him to read and write, and had him almost always with him. Indeed, it was not surprising that Mr Barlow showed so particular an affection for him; for besides learning, with the greatest readiness, everything that was taught him, little Harry was the most honest, obliging creature in the world. He was never discontented, nor did he ever grumble, whatever he was desired to do. And then you might believe Harry in everything he said; for though he could have gained a plum-cake by telling an untruth, and was sure that speaking the truth would expose him to a severe whipping, he never hesitated in declaring it. Nor was he like many other children, who place their whole happiness in eating: for give him but a morsel of dry bread for his dinner, and he would be satisfied, though you placed sweetmeats and fruit, and every other nicety, in his way.

With this little boy did Master Merton become acquainted in the following manner:—As he and the maid were once walking in the fields on a fine summer’s morning, diverting themselves with gathering different kinds of wild flowers, and running after butterflies, a large snake, on a sudden, started up from among some long grass, and coiled itself round little Tommy’s leg. You may imagine the fright they were both in at this accident; the maid ran away shrieking for help, while the child, who was in an agony of terror, did not dare to stir from the place where he was standing. Harry, who happened to be walking near the place, came running up, and asked what was the matter. Tommy, who was sobbing most piteously, could not find words to tell him, but pointed to his leg, and made Harry sensible of what had happened. Harry, who, though young, was a boy of a most courageous spirit, told him not to be frightened; and instantly seizing the snake by the neck, with as much dexterity as resolution, tore him from Tommy’s leg, and threw him to a great distance off.

“Harry, instantly seizing the snake by the neck, with as much dexterity as resolution, tore him from Tommy’s leg and threw him to a great distance off.”

Just as this happened, Mrs Merton and all the family, alarmed by the servant’s cries, came running breathless to the place, as Tommy was recovering his spirits, and thanking his brave little deliverer. Her first emotions were to catch her darling up in her arms, and, after giving him a thousand kisses, to ask him whether he had received any hurt. “No,” said Tommy, “indeed I have not, mamma; but I believe that nasty ugly beast would have bitten me, if that little boy had not come and pulled him off.” “And who are you, my dear,” said she, “to whom we are all so obliged?” “Harry Sandford, madam.” “Well, my child, you are a dear, brave little creature, and you shall go home and dine with us.” “No, thank you, madam; my father will want me.” “And who is your father, my sweet boy?” “Farmer Sandford, madam, that lives at the bottom of the hill.” “Well, my dear, you shall be my child henceforth; will you?” “If you please, madam, if I may have my own father and mother, too.”

Mrs Merton instantly despatched a servant to the farmer’s; and, taking little Harry by the hand, she led him to the mansion-house, where she found Mr Merton whom she entertained with a long account of Tommy’s danger and Harry’s bravery.

Harry was now in a new scene of life. He was carried through costly apartments, where everything that could please the eye, or contribute to convenience, was assembled. He saw large looking-glasses in gilded frames, carved tables and chairs, curtains made of the finest silk, and the very plates and knives and forks were of silver. At dinner he was placed close to Mrs Merton, who took care to supply him with the choicest bits, and engaged him to eat, with the most endearing kindness; but, to the astonishment of everybody, he neither appeared pleased nor surprised at anything he saw. Mrs Merton could not conceal her disappointment; for, as she had always been used to a great degree of finery herself, she had expected it should make the same impression upon everybody else. At last, seeing him eye a small silver cup with great attention, out of which he had been drinking, she asked him whether he should not like to have such a fine thing to drink out of; and added, that, though it was Tommy’s cup, she was sure he would with great pleasure, give it to his little friend. “Yes, that I will,” says Tommy; “for you know, mamma, I have a much finer one than that, made of gold, besides two large ones made of silver.” “Thank you with all my heart,” said little Harry; “but I will not rob you of it, for I have a much better one at home.” “How!” said Mrs Merton, “does your father eat and drink out of silver?” “I don’t know, madam, what you call this; but we drink at home out of long things made of horn, just such as the cows wear upon their heads.” “The child is a simpleton, I think,” said Mrs Merton: “and why is that better than silver ones?” “Because,” said Harry, “they never make us uneasy.” “Make you uneasy, my child!” said Mrs Merton, “what do you mean?” “Why, madam, when the man threw that great thing down, which looks just like this, I saw that you were very sorry about it, and looked as if you had been just ready to drop. Now, ours at home are thrown about by all the family, and nobody minds it.” “I protest,” said Mrs Merton to her husband, “I do not know what to say to this boy, he makes such strange observations.”

The fact was, that during dinner, one of the servants had thrown down a large piece of plate, which, as it was very valuable, had made Mrs Merton not only look very uneasy, but give the man a very severe scolding for his carelessness.

After dinner, Mrs Merton filled a large glass of wine, and giving it to Harry, bade him drink it up, but he thanked her, and said he was not dry. “But, my dear,” said she, “this is very sweet and pleasant, and as you are a good boy, you may drink it up.” “Ay, but, madam, Mr Barlow says that we must only eat when we are hungry, and drink when we are dry: and that we must only eat and drink such things are as easily met with; otherwise we shall grow peevish and vexed when we can’t get them. And this was the way that the Apostles did, who were all very good men.”

Mr Merton laughed at this. “And pray,” said he, “little man, do you know who the Apostles were?” “Oh! yes, to be sure I do.” “And who were they?” “Why, sir, there was a time when people were grown so very wicked, that they did not care what they did; and the great folks were all proud, and minded nothing but eating and drinking and sleeping, and amusing themselves; and took no care of the poor, and would not give a morsel of bread to hinder a beggar from starving; and the poor were all lazy, and loved to be idle better than to work; and little boys were disobedient to their parents, and their parents took no care to teach them anything that was good; and all the world was very bad, very bad indeed. And then there came from Heaven the Son of God, whose name was Christ; and He went about doing good to everybody, and curing people of all sorts of diseases, and taught them what they ought to do; and He chose out twelve other very good men, and called them Apostles; and these Apostles went about the world doing as He did, and teaching people as He taught them.

And they never minded what they did eat or drink, but lived upon dry bread and water; and when anybody offered them money, they would not take it, but told them to be good, and give it to the poor and sick: and so they made the world a great deal better. And therefore it is not fit to mind what we live upon, but we should take what we can get, and be contented; just as the beasts and birds do, who lodge in the open air, and live upon herbs, and drink nothing but water; and yet they are strong, and active, and healthy.”

“Upon my word,” said Mr Merton, “this little man is a great philosopher; and we should be much obliged to Mr Barlow if he would take our Tommy under his care; for he grows a great boy, and it is time that he should know something. What say you, Tommy, should you like to be a philosopher?” “Indeed, papa, I don’t know what a philosopher is; but I should like to be a king, because he’s finer and richer than anybody else, and has nothing to do, and everybody waits upon him, and is afraid of him.” “Well said, my dear,” replied Mrs Merton; and rose and kissed him; “and a king you deserve to be with such a spirit; and here’s a glass of wine for you for making such a pretty answer. And should you not like to be a king too, little Harry?” “Indeed, madam, I don’t know what that is; but I hope I shall soon be big enough to go to plough, and get my own living; and then I shall want nobody to wait upon me.”

“What a difference between the children of farmers and gentlemen!” whispered Mrs Merton to her husband, looking rather contemptuously upon Harry. “I am not sure,” said Mr Merton, “that for this time the advantage is on the side of our son:—But should you not like to be rich, my dear?” said he, turning to Harry. “No, indeed, sir.” “No, simpleton!” said Mrs Merton: “and why not?” “Because the only rich man I ever saw, is Squire Chase, who lives hard by; and he rides among people’s corn, and breaks down their hedges, and shoots their poultry, and kills their dogs, and lames their cattle, and abuses the poor; and they say he does all this because he’s rich; but everybody hates him, though they dare not tell him so to his face—and I would not be hated for anything in the world.” “But should you not like to have a fine laced coat, and a coach to carry you about, and servants to wait upon you?” “As to that, madam, one coat is as good as another, if it will but keep me warm; and I don’t want to ride, because I can walk wherever I choose; and, as to servants, I should have nothing for them to do, if I had a hundred of them.” Mrs Merton continued to look at him with astonishment, but did not ask him any more questions.

In the evening, little Harry was sent home to his father, who asked him what he had seen at the great house, and how he liked being there. “Why,” replied Harry, “they were all very kind to me, for which I’m much obliged to them: but I had rather have been at home, for I never was so troubled in all my life to get a dinner. There was one man to take away my plate, and another to give me drink, and another to stand behind my chair, just as if I had been lame or blind, and could not have waited upon myself; and then there was so much to do with putting this thing on, and taking another off, I thought it would never have been over; and, after dinner, I was obliged to sit two whole hours without ever stirring, while the lady was talking to me, not as Mr Barlow does, but wanting me to love fine clothes, and to be a king, and to be rich, that I may be hated like Squire Chase.”

But at the mansion-house, much of the conversation, in the meantime, was employed in examining the merits of little Harry. Mrs Merton acknowledged his bravery and openness of temper; she was also struck with the very good-nature and benevolence of his character, but she contended that he had a certain grossness and indelicacy in his ideas, which distinguish the children of the lower and middling classes of people from those of persons of fashion. Mr Merton, on the contrary, maintained, that he had never before seen a child whose sentiments and disposition would do so much honour even to the most elevated situations. Nothing, he affirmed, was more easily acquired than those external manners, and that superficial address, upon which too many of the higher classes pride themselves as their greatest, or even as their only accomplishment; “nay, so easily are they picked up,” said he, “that we frequently see them descend with the cast clothes to maids and valets; between whom and their masters and mistresses there is little other difference than what results from the former wearing soiled clothes and healthier countenances. Indeed, the real seat of all superiority, even of manners, must be placed in the mind: dignified sentiments, superior courage, accompanied with genuine and universal courtesy, are always necessary to constitute the real gentleman; and where these are wanting, it is the greatest absurdity to think they can be supplied by affected tones of voice, particular grimaces, or extravagant and unnatural modes of dress; which, far from becoming the real test of gentility, have in general no other origin than the caprice of barbers, tailors, actors, opera-dancers, milliners, fiddlers, and French servants of both sexes. I cannot help, therefore, asserting,” said he, very seriously, “that this little peasant has within his mind the seeds of true gentility and dignity of character; and though I shall also wish that our son may possess all the common accomplishments of his rank, nothing would give me more pleasure than a certainty that he would never in any respect fall below the son of farmer Sandford.”

Whether Mrs Merton fully acceded to these observations of her husband, I cannot decide; but, without waiting to hear her particular sentiments, he thus went on:—”Should I appear more warm than usual upon this subject, you must pardon me, my dear, and attribute it to the interest I feel in the welfare of our little Tommy. I am too sensible that our mutual fondness has hitherto treated him with rather too much indulgence. While we have been over-solicitous to remove from him every painful and disagreeable impression, we have made him too delicate and fretful; our desire of constantly consulting his inclinations has made us gratify even his caprices and humours; and, while we have been too studious to preserve him from restraint and opposition, we have in reality been ourselves the cause that he has not acquired even the common attainments of his age and situation. All this I have long observed in silence, but have hitherto concealed, both from my fondness for our child, and my fear of offending you; but at length a consideration of his real interests has prevailed over every other motive, and has compelled me to embrace a resolution, which I hope will not be disagreeable to you—that of sending him directly to Mr Barlow, provided he would take the care of him; and I think this accidental acquaintance with young Sandford may prove the luckiest thing in the world, as he is so nearly the age and size of our Tommy. I shall therefore propose to the farmer, that I will for some years pay for the board and education of his little boy, that he may be a constant companion to our son.”