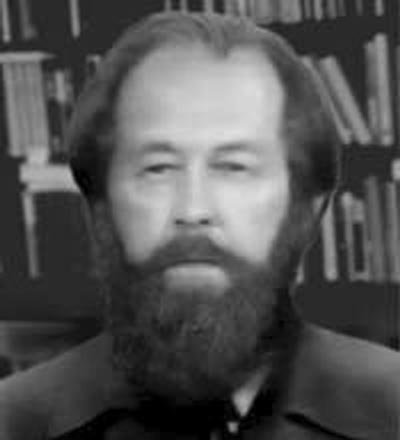

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn descended from an intellectual Cossack family. He was born in Kislovodsk in the northern Caucasus Mountains, between the Black and Caspian seas. His father, Isaaki Solzhenitsyn, a Tsarist artillery officer, was killed in an hunting accident six months before Aleksandr’s birth. During WW I he served on the front, where he married Taissia Shchberbak, Solzhenitsyn’s mother.

To support herself and her son, Taissia worked in Rostov as a typist and did extra work in the evenings. Because the family was extremely poor, Solzhenitsyn had to give up his plans to study literature in Moscow. Instead he enrolled in Rostov University, where he studied mathematics and physics, graduating in 1941. In 1939-41 he took correspondence courses in literature at Moscow State University. In 1940 he married Natalia Alekseevna Reshetovskaia, they divorced in 1950, remarried in 1957, and divorced again in 1972. In 1973 Solzhenitsyn married Natalia Svetlova; they had three sons, Yermolai, Stephan, and Ignat. Dmitri was the son from Svetlova’s first marriage to Prof. Andrei Tiurin. Svetlova, born in 1939, was a postgraduate of the mechanical department of Moscow State University.

In WW II Solzhenitsyn achieved the rank of captain of artillery and was twice decorated. From 1945 to 1953 he was imprisoned for writing a letter in which he criticized Joseph Stalin—“the man with the mustache.” Solzhenitsyn served in the camps and prisons near Moskow, and in a camp in Ekibastuz, Kazakhstan (1945-53). During these years, Solzhenitsyn’s double degree in mathematics and physics saved him mostly from hard physical labour, although in 1950 he was taken to a new kind of camp, created for political prisoners only, where he worked as a manual labourer.

From Marfino, a specialized prison that employed mathematicians and scientist in research, Solzhenitsyn was transferred to forced-labour camp in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic; there he developed stomach cancer. Between 1953 and 1956 Solzhenitsyn was exiled to South Kazakhstan village of Kok-Terek, supporting himself as a mathematics and physics teacher. Solzhenitsyn also wrote in secret. He developed a cancer, but was successfully treated in Tashkent (1954-55). Later these experiences became basis for the novels First Circle and Cancer Ward. After rehabilitation Solzhenitsyn settled in Riazan as a teacher (1957).

At the age of 42, Solzhenitsy had written a great deal secretly, but published nothing. After Nikita Khrushchev had publicly condemned the “cult of personality”—an attack on Stalin’s heritage—the political censorship loosened its tight grip. Solzhenitsyn’s first book, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, appeared next year in the leading Soviet literary journal Novyi Mir. It marked the beginning of Soviet prison-camp literature. Solzhenitsyn used third-person direct speech, examining the Soviet life through the eyes of a simple Everyman. Written in direct style, it described the horrors of just one day in a labour camp. The book gained fame both in the USSR and the West, and was compared with Fedor Dostoyevsky’s novel House of the Dead.

The First Circle (1968) was set during the late 1940s and early 1950s, and drew a picture of a class of intellectuals, research scientists, caught up in the system of prisons and camps. They are forced to work for the secret police, and debate endlessly about politics and the principles of morality. The title of the book referred to the least painful circle of Hell in Dante’s Inferno. However, if the prisoners do not produce satisfactory work, they will found themselves in the lower circles of the labour camps.

The period of official favour lasted only a few years. Between the years 1963 and 1966 Solzhenitsyn managed to publish only four stories and finally all his manuscripts were censored. Khrushchev himself was forced into retirement in 1964. The KGB confiscated the novel V Kruge Pervon and other writings in 1965. Solzhenitsyn refused to join his colleagues who protested prison sentences imposed on the writers, because he “disapproved of writers who sought fame abroad”, but in 1969 he was expelled in absentia from the Writers’ Union. “Dust off the clock face,” Solzhenitsyn said in his open letter after the expulsion. “You are behind the times. Throw open the sumptuous heavy curtain; you do not even suspect that day is already dawning outside.” From 1971 his unpublished manuscripts were smuggled in the West. These works secured Solzhenitsyn’s international fame as one of the most prominent opponents of government policies.

Rejecting the ideology of his youth, Solzhenitsyn came to believe that the struggle between good and evil cannot be resolved among parties, classes or doctrines, but is waged within the individual human heart. During the Cold War years, this Tolstoian view and search for Christian morality was considered radical in the ideological atmosphere of the Soviet Union in the 1960s and 1970s.

The first volume of The Gulag Archipelago appeared in 1973. (Gulag stands for “Chief Administration of Corrective Labour Camps.”) For the work Solzhenitsyn collected excerpts from documents, oral testimonies, eyewitness reports, and other material, which all was inflammable. The detailed account of the network of prison and labour camps—scattered like islands in a sea—in Stalin’s Russia angered the Soviet authorities and Solzhenitsyn was arrested and charged with treason. “A great writer is, so to speak, a second government in his country,” Solzhnenitsyn wrote in The First Circle. “And for that reason no regime has ever loved great writers, only minor ones.”

As with Boris Pasternak, the Soviet government denounced Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel Prize as a politically hostile act. “If Solzhenitsyn continues to reside in the country after receiving the Nobel Prize, it will strenghten his position, and allow him to propaganda his views more actively,” wrote the KGB chief Yuri Andropov in a secret memorandum.

In 1974 the author was exiled from the Soviet Union. He lived first in Switzerland and moved then in 1976 to the United States, where he continued to write series called The Red Wheel, an epic history of the events, that led to the Russian Revolution. August 1914 (1971), constructed in fragmented style, focused on the defeat of the Russian Second Army in East Prussia. Although Solzhenitsyn did not have much sympathy for intentionally experimental, avant-garde literature, he used also in this work documents, proverbs, songs, newspapers, and imitation film scripts. With these technical devices Solzhenityn managed to create a broad social picture of this crucial moment of history.

After collapse of the Soviet Union Solzhenitsyn returned from Vermont to his home land in 1994. The new regime, led by Mikhail S. Gorbachev, had offered to restore his citizenship already in 1990, and next year his treason charges were formally dropped. Solzhenitsyn made a sensational whistle-stop tour through Siberia, becoming a highly popular figure. Solzhenitsyn was also received by President Yeltsin and in 1994 he gave an address to Russian Duma.

Solzhenitsyn settled in Moscow, where he has continued to criticize western materialism and Russian bureaucracy and secularization. Western democratic system means for Solzhenitsyn “spiritual exhaustion” in which “mediocrity triumphs under the guise of democratic restraints.” Sozhenitsyn’s old Russian ideals were already explicit in the character of Matryona in ‘Matryona’s House’. Its narrator meets a saintly woman, whose life has been full of disappointments but who helps others. “We had lived side by side her and had never understood that she was the righteous one without whom,. as the proverb says, no village can stand.”

Solzhenitsyn’s message is clear—the only salvation is to abandon materialist world view and return to the virtues of Holy Russia—but his message has not led to concrete consequences. Solzhenitsyn’s talk show was cancelled due to low ratings. However, the television adaptation of The First Circle, broadcasted in 2006, gained a huge audience.

The Solzhenitsyn Prize for Russian writing was established in 1997. Since his return Solzhenitsyn has published several works, but in the West his views have not gained the former interest. However, the essay Rebuilding Russia (1990) was widely read and arose much debate. Solzhenitsyn’s later books include Rossiya V Obvale (1998, Russia Collapsing), an attack on Russia’s business circles and government, published by Viktor Moskvin. He has also written two volumes on Russian-Jewish relations.