Chapter 5

Maxim Rang up the next morning to say he would be back about seven. Frith took the message. Maxim did not ask to speak to me himself. I heard the telephone ring while I was at breakfast and I thought perhaps Frith would come into the dining-room and say, “Mr. de Winter on the telephone, Madam.” I had put down my napkin and had risen to my feet. And then Frith came back into the dining-room and gave me the message.

He saw me push back my chair and go to the door. “Mr. de Winter has rung off, Madam,” he said, “there was no message. Just that he would be back about seven.” I sat down in my chair again and picked up my napkin. Frith must have thought meager and stupid rushing across the dining-room. “All right, Frith. Thank you,” I said. I went on eating my eggs and bacon, Jasper at my feet, the old dog in her basket in the corner. I wondered what I should do with my day. I had slept badly; perhaps because I was alone in the room. I had been restless, waking up often, and when I glanced at my clock I saw the hands had scarcely moved.

When I did fall asleep I had varied, wandering dreams. We were walking through the woods, Maxim and I, and he was always just a little ahead of me. I could not keep up with him. Nor could I see his face. Just his figure, striding away in front of me all the time. I must have cried while I slept, for when I woke in the morning the pillow was damp. My eyes were heavy too, when I looked in the glass. I looked plain, unattractive. I rubbed a little rouge on my cheeks in a wretched attempt to give myself colour. But it made me worse. It gave me a false clown look. Perhaps I did not know the best way to put it on. I noticed Robert staring at me as I crossed the hall and went in to breakfast. About ten o’clock as I was crumbling some pieces for the birds on the terrace the telephone rang again.

This time it was for me. Frith came and said Mrs. Lacy wanted to speak to me. “Good morning, Beatrice,” I said. “Well, my dear, how are you?” she said, her telephone voice typical of herself, brisk, rather masculine, standing no nonsense, and then not waiting for my answer, “I thought of motoring over this afternoon and looking up Gran. I’m lunching with people about twenty miles from you. Shall I come and pick you up and we’ll go together? It’s time you met the old lady, you know.”

“I’d like to very much, Beatrice,” I said, “Splendid. Very well, then, I’ll come along for you about half-past three.” Giles saw Maxim at the dinner. “Poor food,” he said, “but excellent wine. All right, my dear, see you later.” The click of the receiver, and she was gone. I wandered back into the garden. I was glad she had rung up and suggested the plan of going over to see the grandmother. It made something to look forward to, and broke the monotony of the day. The hours had seemed so long until seven o’clock. I did not feel in my holiday mood to-day, and I had no wish to go off with Jasper to the Happy Valley and come to the cove and throw stones in the water.

The sense of freedom had departed, and the childish desire to run across the lawns in sand-shoes. I went and sat down with a book and The Times and my knitting in the rose-garden, domestic as a matron, yawning in the warm sun while the bees hummed amongst the flowers. I tried to concentrate on the bald newspaper columns, and later to lose myself in therapy plot of the novel in my hands. I did not want to think of yesterday afternoon and Mrs. Danvers. I tried to forget that she was in the house at this moment, perhaps looking down on me from one of the windows. And now and again, when I looked up from my book or glanced across the garden, I had the feeling I was not alone.

There were so many windows in Manderley, so many rooms that were never used by Maxim and myself that were empty now, dust-sheeted, silent, rooms that had been occupied in the old days when his father and his grandfather had been alive, when there had been much entertaining, many servants.

It would be easy for Mrs. Danvers to open those doors softly and close them again, and then steal quietly across the shrouded room and look down upon me from behind the drawn curtains. I should not know.

Even if I turned in my chair and looked up to the windows I wouldn’t see her. I remembered a game I had played as a child that my friends next door had called ‘Grandmother’s Steps’ and myself ‘Old Witch.’ You had to stand at the end of the garden with your back turned to the rest, and one by one they crept nearer to you, advancing in short furtive fashion.

Every few minutes you turned to look at them, and if you saw one of them moving the offender had to retire to the back line and begin again. But there was always one a little bolder than the rest, who came up very close, whose movement was impossible to detect, and as you waited there, your back turned, counting the regulation Ten, you knew, with a fatal terrifying certainty, that before long, before even the Ten was counted, this bold player would pounce upon you from behind, unheralded, unseen, with a scream of triumph. I felt as tense and expectant as I did then. I was playing ‘Old Witch’ with Mrs. Danvers. Lunch was a welcome break to the long morning.

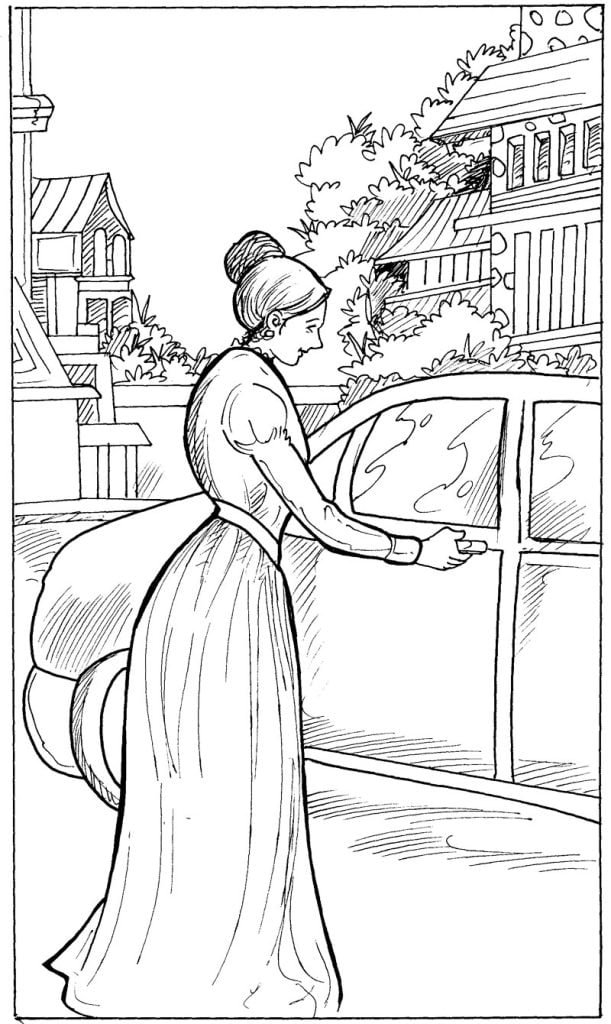

The calm efficiency of Frith, and Robert’s rather foolish face, helped me more than my book and my newspaper had done. And at half-past three, punctual to the moment, I heard the sound of Beatrice’s scar round the sweep of the drive and pull up at the steps before the house. I ran out to meet her, ready dressed, my gloves in my hand. “Well, my dear, here I am, what a splendid day, isn’t it?” She slammed the door of the car and came up the steps to meet me. She gave me a hard swift kiss, brushing me somewhere near the ear. “You don’t look well,” she said immediately, looking me up and down, “much too thin in the face, and no colour. What’s wrong with you?”

“Nothing,” I said humbly, knowing the fault of my face too well. “I’m not a person whoever has much colour.”

“Oh, bosh,” she replied, “you looked quite different when I saw you before.”

“I expect the brown of Italy has worn off,” I said, getting into the car. “H’mph,” she said shortly, “you’re as bad as Maxim. Can’t stand any criticism about your health. Slam the door hard or it doesn’t shut.” We started off down the drive, swerving at the corner, going rather too fast. “You’re not by any chance starting an infant, are you?” She said, turning her hawk-brown eyes upon me. “No,” I said awkwardly, “No, I don’t think so. No morning sickness or anything like that?”

“No.”

“Oh, well—of course it doesn’t always follow. I never turned a hair when Roger was born. Felt as fit as a fiddle the whole nine months. I played golf the day before he arrived. There’s nothing to be embarrassed about in the facts of nature, you know. If you have any suspicions you had better tell me.”

“No, really, Beatrice,” I said, “there’s nothing to tell.”

“I must say I do hope you will produce a son and heir before long. It would be so terribly good for Maxim. I hope you are doing nothing to prevent it.”

“Of course not,” I said. What an extraordinary conversation. “Oh, don’t be shocked,” she said, “you must never mind what I say. After all, brides of to-day are up to everything. It’s a damn nuisance if you want to hunt and you land yourself with an infant your first season. Quite enough to break a marriage up if you’re both keen. Wouldn’t matter in your case. Babies needn’t interfere with sketching. How is the sketching, by-the-way?”

“I’m afraid I don’t seem to do much,” I said, “Oh, really? Nice weather too, for sitting out of doors. You only need a camp-stool and a box of pencils, don’t you? Tell me, were you interested in those books I sent you?”

“Yes, of course,” I said, “It was a lovely present, Beatrice.”

She looked pleased. “Glad you liked them,” she said. The car sped along. She kept her foot permanently on the accelerator, and took every corner at an acute angle. Two motorists we passed looked out of their windows outraged as she swept by, and one pedestrian in a lane waved his stick at her. I felt rather hot for her. She did not seem to notice though. I crouched lower in my seat. “Roger goes up to Oxford next term,” she said, “heaven knows what he’ll do with himself. Awful waste of time I think, and so does Giles, but we couldn’t think what else to do with him.”

Of course he’s just like Giles and myself. Thinks of nothing but horses. What on earth does this car in front think it’s doing? Why don’t you put out your hand, my good man? Really, some of these people on the road to-day ought to be shot. We swerved into a main road, narrowly avoiding the car ahead of us. “Had any people down to stay?” she asked. “No, we’ve been very quiet,” I said. “Much better, too,” she said, “awful bore, I always think, those big parties. You won’t find it alarming if you come to stay with us. Very nice lot of people all round, and we all know one another frightfully well. We dine in one another’s houses, and have our bridge, and don’t bother with outsiders. You do play bridge, don’t you?”

“I’m not very good, Beatrice.”

“Oh, we shan’t mind that. As long as you can play. I’ve no patience with people who won’t learn. What on earth can one do with them between tea and dinner in the winter, and after dinner? One can’t just sit and talk.” I wondered why. However, it was simpler not to say anything. “It’s quite amusing now Roger is a reasonable age,” she went on, “because he brings his friends to stay, and we have really good fun. You ought to have been with us last Christmas. We had charades. My dear, it was the greatest fun. Giles was in his element. He adores dressing-up, you know, and after a glass of two of champagne he’s the funniest thing you’ve ever seen. We often say he’s missed his vocation and ought to have been on the stage.” I thought of Giles, and his large moon face, his horn spectacles. I felt the sight of him being funny after champagne would embarrass me. “He and another man, a great friend of ours, Dickie Marsh, dressed up as women and sang a duet.”

What exactly it had to do with the word in the charade nobody knew, but it did not matter. We all roared. I smiled politely. “Fancy, how funny,” I said. I saw them all rocking from side to side in Beatrice’s drawing-room. All these friends who knew one another so well. Roger would look like Giles. Beatrice was laughing again at the memory. “Poor Giles,” she said, “I shall never forget his face when Dick squirted the soda syphon down his back. We were all in fits.

❒