Chapter-9

The next morning I explained to Mr Spenlow that I needed a few days away to visit a dying friend, and left at noon for Yarmouth. I took a room at the hotel because it was late evening when the coach pulled into the village. At ten o’clock I went out for an evening’s walk, to fill myself with the smell of the sea and think of my dear friend Peggotty and of Barkis, whose quiet, countrified ways I would miss.

Then I walked the few blocks to Peggotty’s cottage. Daniel answered my soft tap at the front door. Em’ly was sitting by the fire with her face in her hands, Ham beside her.

I heard their news of Barkis and of Peggotty spoken in whispers. Everyone was subdued, given the presence of Death in the house, but Em’ly most of all. She seemed to be a vapour, a mist, less than present, drained of all the usual colour in her cheeks and eyes—pale, almost transparent, and filled with tears.

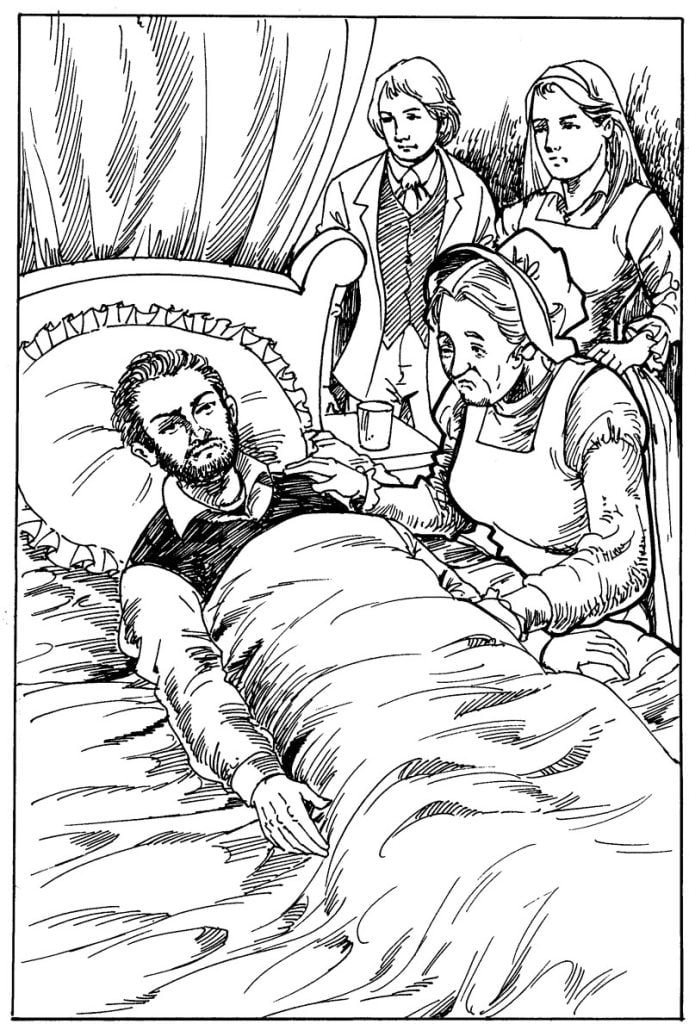

Peggotty came down from Barkis’ bedside because she said she’d heard my voice. She hugged me and I felt her shaking. “Come up with me, Davy,” she said, “Barkis has always loved and admired you.”

We went up the stairs and I stood beside the old cart driver. His eyes didn’t open, his fingers lay still, and there was barely any movement of his chest under the cover.

Daniel came into the room and stood beside me. “He’s going out with the tide,” he whispered.

“With the tide?”

“People along the seacoast can’t die until the tide’s out. Can’t be born unless it’s in either. He’s waiting for the tide to go.”

We stayed by Barkis’ bed for hours. At the end he opened his eyes, searching for Peggotty; he lightly squeezed my hand, and died.

I saw Daniel glance at the clock on the bed table. “Tide’s out,” he said.

There was not much ceremony for Barkis’ burial. He was taken to Blunderstone and placed in the graveyard beside the Rookery. I stayed on in Yarmouth to attend to his will.

During the days after the funeral I saw nothing of Em’ly, but Daniel told me she was to be married quietly in two weeks. Peggotty and I made arrangements to leave for London where we would file the will and estate papers with the court.

Rain was falling heavily the night before our trip. Wind howled in off the sea and splashed the windows. When the rain slowed to a drizzle and the moon came out I slogged across the wet sand to the boat-house to say goodbye to Daniel and Ham and Em’ly. The house was bright and warm, fire blazing, pipe smoke scenting the air around Daniel. Peggotty was there, sewing. But there was no Em’ly and no Ham. I sat and watched the fire peacefully with sister and brother, feeling the old kinship of years before.

Not ten minutes had passed when Ham came through the door, looking storm-tossed and pale, wet to the skin.

“Where’s Em’ly?” asked Daniel.

Ham made a movement with his head that seemed to mean she was outside. “Davy, will you come out a moment and see what we have to show you?” he asked me.

He pulled me into the open air and closed the door behind him. Em’ly was not there.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

He began to cry, broken-hearted wails and gasps were all he could produce. No words, No answers. I didn’t know what to do in the face of such grief. I could only look at him and repeat my question.

“She’s gone, Davy. She’s run away. What am I going to do? What am I going to say to Daniel? You know how he loves her.”

I was standing with my back to the rain, facing Ham and the front door. There was no time to reach around the sobbing man and grip the handle when I saw the door start to open. Daniel thrust his head towards us.

“Where is she, Ham? What’s happened to my little girl?” he asked with a look of fear that I had never seen the equal of.

We went inside and Ham read from a note Em’ly had left for him.

“When you see this, I will be far away,” he began. “Tell Uncle Daniel that I loved him, and that my heart is torn to leave this way. Love some good woman, Ham—one who will love you as much as you love me. God bless you all.”

The reading was slow and difficult for Ham. Everyone sat looking at him for a moment when he finished.

Ham raised his head and looked at me. “I don’t want you to think I blame you at all, Davy. It wasn’t your doing that Em’ly left us.”

I felt the stab of truth in my belly. “Who has she gone away with?” I asked, already certain I knew the answer.

“Mr Omer said he saw a strange carriage in town this morning, and in it a man he’d seen at the boatyards several times. Another man, Omer said a servant of some sort, made two trips to and from the carriage, both times carrying boxes and bags, and the second time Em’ly was with him. She got into the carriage, and all rode away. By the way Omer spoke of the man in the carriage, I know it was James Steerforth, and his man Littimer.”

Daniel walked to the bank of coats and scarves hanging inside the door, and took his rough jacket from its peg at the end. Ham asked where he was going.

“I’m going to find her. First I’m going to sink that boat of his—The Little Em’ly, he called it. Then I’m going to find her—and I won’t rest until I know she’s safe, whether here or somewhere else.”

Ham stepped over beside the door. “Daniel, the baggage man heard Littimer tell the driver they were going to London and then across the Channel to France.”

“They’re well into London and may already have sailed for the Continent, I said.

“I won’t be stopped,” Daniel exclaimed, “Whether I began now or tomorrow, no difference. I won’t quit until I find her. If that snake is her honest choices, so be it. But I must know it with my own mind.”

“Keep the candle in the window every night, Ham,” he instructed, “Don’t let it burn out in case Em’ly comes home. I’ve burned it there for so many years, and when she sees it she’ll know she’s welcome to her home and our hearts.”

In the morning, Ham drove Daniel, Peggotty, and me to the London coach. Before we three boarded, Ham took me aside.

“There’s no changing his mind, Davy. She’s the centre of his heart—always has been since she was orphaned by the sea. Try to keep in touch with him, Davy.”

“I’ll do what I can,” was all I could promise. Arriving in London that afternoon we got a room where Peggotty could stay while Barkis’ estate was being finalized, then all went to dinner in the hotel restaurant. I asked Daniel about his plans, where he meant to go, but all he would answer was, “I’m going to look for Em’ly.”

Folding his napkin and laying it beside his coffee cup, he rose and said it was time to leave. We walked with him to the hotel porch. He promised to keep in touch often to let us know where he was and how his search was going, but more than that he wouldn’t say.

It was a warm, dusty evening with a ruby sunset. Daniel hugged Peggotty and me, then stepped off the porch and into the road. He turned, alone, at the corner of the shady street, into a glow of fading sunlight, and was gone.