Chapter-4

Dorian Gray listened, open-eyed and wondering. The spray of lilac fell from his hand upon the gravel. A furry bee came and buzzed round it for a moment. Then it began to scramble all over the fretted purple of the tiny blossoms. He watched it with that strange interest in trivial things that we try to develop when things of high import make us afraid, or when we are stirred by some new emotion, for which we cannot find expression, or when some thought that terrifies us lays sudden siege to the brain and calls on us to yield. After a time it flew away. He saw it creeping into the stained trumpet of a Tyrian convolvulus. The flower seemed to quiver, and then swayed gently to and fro.

Suddenly Hallward appeared at the door of the studio, and made frantic signs for them to come in. They turned to each other, and smiled.

‘I am waiting,’ cried Hallward, ‘Do come in. The light is quite perfect, and you can bring your drinks.’

They rose up, and sauntered down the walk together. Two green and white butterflies fluttered past them, and in the pear-tree at the end of the garden a thrush began to sing.

‘You are glad you have met me, Mr. Gray,’ said Lord Henry, looking at him.

‘Yes, I am glad now. I wonder shall I always be glad?’

‘Always! That is a dreadful word. It makes me shudder when I hear it. Women are so fond of using it. They spoil every romance by trying to make it last forever. It is a meaningless word, too. The only difference between a caprice and a life-long passion is that the caprice lasts a little longer.’

As they entered the studio, Dorian Gray put his hand upon Lord Henry’s arm. ‘In that case, let our friendship be a caprice,’ he murmured, flushing at his own boldness, then stepped upon the platform and resumed his pose.

Lord Henry flung himself into a large wicker arm-chair, and watched him. The sweep and dash of the brush on the canvas made the only sound that broke the stillness, except when Hallward stepped back now and then to look at his work from a distance. In the slanting beams that streamed through the open door-way the dust danced and was golden. The heavy scent of the roses seemed to brood over everything.

After about a quarter of an hour, Hallward stopped painting, looked for a long time at Dorian Gray, and then for a long time at the picture, biting the end of one of his huge brushes, and smiling. ‘It is quite finished,’ he cried, at last, and stooping down he wrote his name in thin vermilion letters on the left-hand corner of the canvas.

Lord Henry came over and examined the picture. It was certainly a wonderful work of art, and a wonderful likeness as well.

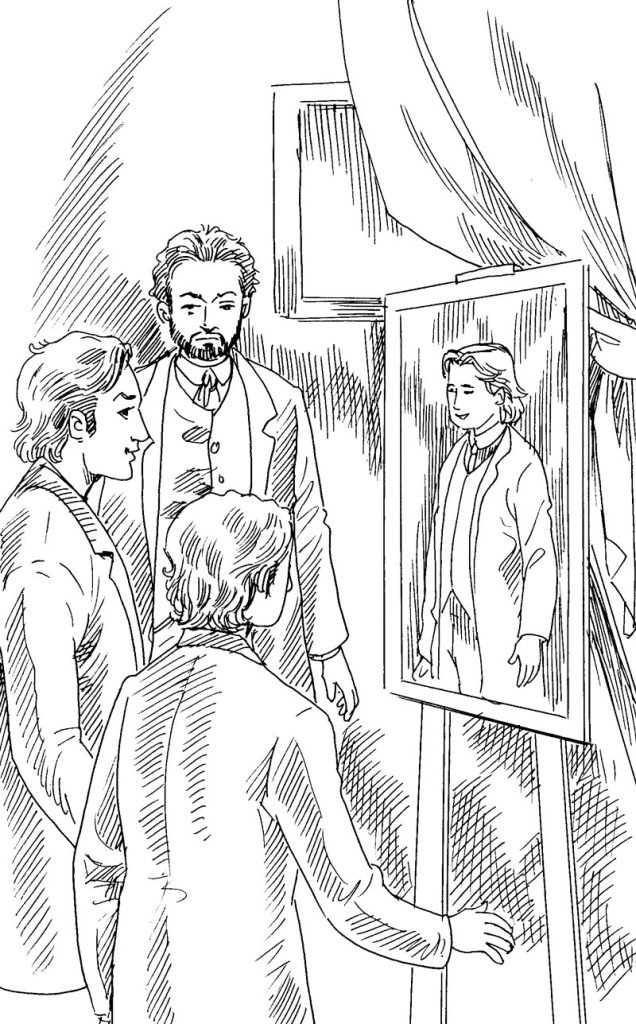

‘My dear fellow, I congratulate you most warmly,’ he said, ‘Mr. Gray, come and look at yourself.’

The lad started, as if awakened from some dream. ‘Is it really finished?’ he murmured, stepping down from the platform.

‘Quite finished,’ said Hallward. ‘And you have sat splendidly today. I am awfully obliged to you.’

‘That is entirely due to me,’ broke in Lord Henry, ‘Isn’t it, Mr. Gray?’

Dorian made no answer, but passed listlessly in front of his picture and turned towards it. When he saw it he drew back, and his cheeks flushed for a moment with pleasure. A look of joy came into his eyes, as if he had recognized himself for the first time. He stood there motionless, and in wonder, dimly conscious that Hallward was speaking to him, but not catching the meaning of his words. The sense of his own beauty came on him like a revelation. He had never felt it before. Basil Hallward’s compliments had seemed to him to be merely the charming exaggerations of friendship. He had listened to them, laughed at them, forgotten them. They had not influenced his nature. Then had come Lord Henry, with his strange panegyric on youth, his terrible warning of its brevity. That had stirred him at the time, and now, as he stood gazing at the shadow of his own loveliness, the full reality of the description flashed across him. Yes, there would be a day when his face would be wrinkled and wizen, his eyes dim and colorless, the grace of his figure broken and deformed. The scarlet would pass away from his lips, and the gold steal from his hair. The life that was to make his soul would mar his body. He would become ignoble, hideous, and uncouth.

As he thought of it, a sharp pang of pain struck like a knife across him, and made each delicate fibre of his nature quiver. His eyes deepened into amethyst, and a mist of tears came across them. He felt as if a hand of ice had been laid upon his heart.

‘Don’t you like it?’ cried Hallward at last, stung a little by the lad’s silence, and not understanding what it meant.

‘Of course he likes it,’ said Lord Henry, ‘Who wouldn’t like it? It is one of the greatest things in modern art. I will give you anything you like to ask for it. I must have it.’

‘It is not my property, Harry.’

‘Whose property is it?’

‘Dorian’s, of course.’

‘He is a very lucky fellow.’

‘How sad it is!’ murmured Dorian Gray, with his eyes still fixed upon his own portrait. ‘How sad it is! I shall grow old, and horrid, and dreadful. But this picture will remain always young. It will never be older than this particular day of June, if it was only the other way! If it was I who were to be always young, and the picture that were to grow old! For this—for this—I would give everything! Yes, there is nothing in the whole world I would not give!’

‘You would hardly care for that arrangement, Basil,’ cried Lord Henry, laughing. ‘It would be rather hard lines on you.’

‘I should object very strongly, Harry.’

Dorian Gray turned and looked at him. ‘I believe you would, Basil. You like your art better than your friends. I am no more to you than a green bronze figure. Hardly as much, I dare say.’

Hallward stared in amazement. It was so unlike Dorian to speak like that. What had happened? He seemed almost angry. His face was flushed and his cheeks burning.

‘Yes,’ he continued, ‘I am less to you than your ivory Hermes or your silver Faun. You will like them always. How long will you like me? Till I have my first wrinkle, I suppose. I know, now, that when one loses one’s good looks, whatever they may be, one loses everything. Your picture has taught me that. Lord Henry is perfectly right. Youth is the only thing worth having. When I find that I am growing old, I will kill myself.’

Hallward turned pale, and caught his hand. ‘Dorian! Dorian!’ he cried, ‘don’t talk like that. I have never had such a friend as you, and I shall never have such another. You are not jealous of material things, are you?’

‘I am jealous of everything whose beauty does not die. I am jealous of the portrait you have painted of me. Why should it keep what I must lose? Every moment that passes takes something from me, and gives something to it. Oh, if it was only the other way! If the picture could change, and I could be always what I am now! Why did you paint it? It will mock me some day,—mock me horribly!’ The hot tears welled into his eyes; he tore his hand away, and, flinging himself on the divan, he buried his face in the cushions, as if he was praying.

‘This is your doing, Harry,’ said Hallward, bitterly.

‘My doing?’

‘Yes, yours, and you know it.’

Lord Henry shrugged his shoulders. ‘It is the real Dorian Gray,—that is all,’ he answered.

‘It is not.’

‘If it is not, what have I to do with it?’

‘You should have gone away when I asked you.’

‘I stayed when you asked me.’

‘Harry, I can’t quarrel with my two best friends at once, but between you both you have made me hate the finest piece of work I have ever done, and I will destroy it. What is it but canvas and color? I will not let it come across our three lives and mar them.’

Dorian Gray lifted his golden head from the pillow, and looked at him with pallid face and tear-stained eyes, as he walked over to the deal painting-table that was set beneath the large curtained window. What was he doing there? His fingers were straying about among the litter of tin tubes and dry brushes, seeking for something. Yes, it was the long palette-knife, with its thin blade of lithe steel. He had found it at last. He was going to rip up the canvas.

With a stifled sob he leaped from the couch, and, rushing over to Hallward, tore the knife out of his hand, and flung it to the end of the studio. ‘Don’t, Basil, don’t!’ he cried. ‘It would be murder!’

‘I am glad you appreciate my work at last, Dorian,’ said Hallward, coldly, when he had recovered from his surprise, ‘I never thought you would.’

‘Appreciate it? I am in love with it, Basil. It is part of myself, I feel that.’

‘Well, as soon as you are dry, you shall be varnished, and framed, and sent home. Then you can do what you like with yourself.’ And he walked across the room and rang the bell for tea. ‘You will have tea, of course, Dorian? And so will you, Harry? Tea is the only simple pleasure left to us.’

‘I don’t like simple pleasures,’ said Lord Henry. ‘And I don’t like scenes, except on the stage. What absurd fellows you are, both of you! I wonder who it was defined man as a rational animal. It was the most premature definition ever given. Man is many things, but he is not rational. I am glad he is not, after all: though I wish you chaps would not squabble over the picture. You had much better let me have it, Basil. This silly boy doesn’t really want it, and I do.’

‘If you let any one have it but me, Basil, I will never forgive you!’ cried Dorian Gray, ‘And I don’t allow people to call me a silly boy.’

‘You know the picture is yours, Dorian. I gave it to you before it existed.’

‘And you know you have been a little silly, Mr. Gray, and that you don’t really mind being called a boy.’

‘I should have minded very much this morning, Lord Henry.’

‘Ah! this morning! You have lived since then.’

There came a knock to the door, and the butler entered with the teatray and set it down upon a small Japanese table. There was a rattle of cups and saucers and the hissing of a fluted Georgian urn. Two globe-shaped china dishes were brought in by a page. Dorian Gray went over and poured the tea out. The two men sauntered languidly to the table, and examined what was under the covers.

‘Let us go to the theatre tonight,’ said Lord Henry. ‘There is sure to be something on, somewhere. I have promised to dine at White’s, but it is only with an old friend, so I can send him a wire and say that I am ill, or that I am prevented from coming in consequence of a subsequent engagement. I think that would be a rather nice excuse: it would have the surprise of candour.’

‘It is such a bore putting on one’s dress-clothes,’ muttered Hallward. ‘And, when one has them on, they are so horrid.’

‘Yes,’ answered Lord Henry, dreamily, ‘the costume of our day is detestable. It is so sombre, so depressing. Sin is the only colorelement left in modern life.’

‘You really must not say things like that before Dorian, Harry.’

‘Before which Dorian? The one who is pouring out tea for us, or the one in the picture?’

‘Before either.’

‘I should like to come to the theatre with you, Lord Henry,’ said the lad.

‘Then you shall come; and you will come too, Basil, won’t you?’

‘I can’t, really. I would sooner not. I have a lot of work to do.’

‘Well, then, you and I will go alone, Mr. Gray.’

‘I should like that awfully.’

Basil Hallward bit his lip and walked over, cup in hand, to the picture. ‘I will stay with the real Dorian,’ he said, sadly.

‘Is it the real Dorian?’ cried the original of the portrait, running across to him, ‘Am I really like that?’

‘Yes; you are just like that.’

‘How wonderful, Basil!’

‘At least you are like it in appearance. But it will never alter,’ said Hallward, ‘That is something.’

‘What a fuss people make about fidelity!’ murmured Lord Henry.

‘And, after all, it is purely a question for physiology. It has nothing to do with our own will. It is either an unfortunate accident, or an unpleasant result of temperament. Young men want to be faithful, and are not; old men want to be faithless, and cannot: that is all one can say.’

‘Don’t go to the theatre tonight, Dorian,’ said Hallward. ‘Stop and dine with me.’

‘I can’t, really.’

‘Why?’

‘Because I have promised Lord Henry to go with him.’

‘He won’t like you better for keeping your promises. He always breaks his own. I beg you not to go.’

Dorian Gray laughed and shook his head.

‘I entreat you.’

The lad hesitated, and looked over at Lord Henry, who was watching them from the tea-table with an amused smile.

‘I must go, Basil,’ he answered.

‘Very well,’ said Hallward; and he walked over and laid his cup down on the tray. ‘It is rather late, and, as you have to dress, you had better lose no time. Goodbye, Harry; goodbye, Dorian. Come and see me soon. Come tomorrow.’

‘Certainly.’

‘You won’t forget?’

‘No, of course not.’

‘And…Harry!’

‘Yes, Basil?’

‘Remember what I asked you, when in the garden this morning.’

‘I have forgotten it.’

‘I trust you.’

‘I wish I could trust myself,’ said Lord Henry, laughing. ‘Come, Mr. Gray, my hansom is outside, and I can drop you at your own place. Goodbye, Basil. It has been a most interesting afternoon.’

As the door closed behind them, Hallward flung himself down on a sofa, and a look of pain came into his face.