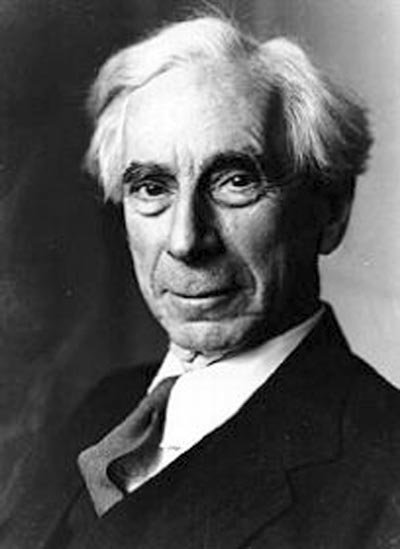

Bertrand Russell was born in Trelleck, Gwent, the second son of Viscount Amberley. His mother, Katherine, was the daughter of Baron Stanley of Aderley. She died in 1874. Her husband died twenty months later, after a long period of gradually increasing debility. At the age of three Russell was an orphan. He was brought up by his grandfather, Lord John Russell, who had been prime minister twice, and his wife Lady John.

Inspired by Euclid’s Geometry, Russell displayed a keen aptitude for pure mathematics and developed an interest in philosophy. However, when he was about fourteen he become interested in theology, but during the following years he rejected free will, immortality, and belief in God. He read widely, mostly books from his grandfather’s library, but it was only at Cambridge, when he started to read such “modern” writers of the early 1890s. At Trinity College, Cambridge, his brilliance was soon recognized, and brought him a membership of the ‘Apostles’, a forerunner of the Bloomsbury Set. After graduating from Cambridge in 1894, Russell worked briefly at the British Embassy in Paris as honorary attache. Next year he became a fellow of Trinity College.

Against his family’s wishes, Russell married an American Quaker, Alys Persall Smith, and went off with his wife to Berlin, where he studied economics and gathered data for the first of his ninety-odd books, German Social Democracy (1896). A year later Russell’s fellowship dissertation, Essay On The Foundations On Geometry (1897) came out.

The Principles Of Mathematics (1903) was Russell’s first major work. It proposed that the foundations of mathematics could be deduced from a few logical ideas. In it Russell arrived at the view of Gottlob Frege (1848-1925), that mathematics is a continuation of logic and that its subject-matter is a system of Platonic essences that exist in the realm outside both mind and matter. Principia Mathematica (1910-13) was written in collaboration with the philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead.

After Principia Russell never again worked intensively in mathematics.

Russell’s concise and original introductory book, The Problems Of Philosophy, appeared in 1912. He continued with works on epistemology, Mysticism And Logic (1918) and Analysis And Mind (1921).

In 1907 Russell stood unsuccessfully for parliament as a candidate for the Women’s Suffragette Society, and the next year he became a Fellow of the Royal Society. Believing that inherited wealth was immoral, Russell gave most of his money away to his university.

At the outbreak of World War I, Russell was an outspoken pacifist, which lost him his fellowship in 1916. At the beginning of the war, he helped orgazine a petition urging that Britain remain neutral. In 1918 Russell served six months in prison, convicted of libelling an ally—the American army—in a Tribune article. Russell visited Russia in 1920 with a Labour Party delegation and met Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, but returned deeply disillusioned and published his sharp criticism, The Practice And Theory Of Bolshevism (1920).

In 1922 Russell celebrated his 50th birthday, believing that “brain becomes rigid at 50.” He was a famous and controversial figure. Russell pursued his philosophical work in The Analysis Of Mind (1921) and The Analysis Of Matter (1927). Between the years 1920 and 1921 he was professor at Peking, and in 1927 he started with his former student and second wife Dora Black a progressive school at Sussex. In On Education (1926) Russell called for an education that would liberate the child from unthinking obedience to parental and religious authority.

The experiment at Beacon Hill lasted for five years and gave material to the book Education And Social Order (1932). In 1936 Russell married Patricia Spencer, who had been his research assistant on his political history Freedom And Organization (1934). In 1938 he moved to the United States, returning to academic philosophical work. He was a visiting professor at the University of California at Los Angeles, and in 1940 he was appointed Professor of Philosophy at the College of the City of New York. The appointment was revoked and he was barred from teaching basically because of his libertarian opinions. From California Russell went to Harvard, where his lectures proceeded without incidents. An appointment from the Barnes Foundation near Philadelphia gave Russell an opportunity to write one of his most popular works, History Of Western Philosophy (1945). Its success permanently ended his financial difficulties and earned him the Nobel Prize. In 1944 Russell returned to Cambridge as a Fellow of his old college, Trinity.

During WW II Russell abandoned his pacifism, but in the final decades of his life he became the leading figure in the antinuclear weapons movement. From 1950 to his death Russell was extremely active in political campaigning. He established the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation in 1964, supported the Jews in Russia and the Arabs in Palestine and condemned the Vietnam War.

Retaining his ability to cause debate, Russell was imprisoned in 1961 with his fourth and final wife Edith Finch for taking part in a demonstration in Whitehall. The sentence was reduced on medical grounds to seven days. His last years Russell spent in North Wales. His later works include Human Knowledge : Its Scope And Limits (1948), two collections of sardonic fables, Satan In The Suburb (1953) and Nightmares Of Eminent Persons (1954), and The Autobiography Of Bertrand Russell (1967-69, 3 vols.), Russell died of influenza on February 2, 1970. When asked what he would say to God if he found himself before Him, Russell answered: ‘I should reproach him for not giving us enough evidence.’