Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi didn’t waste time in Allahabad. He went to Kanpur where his brother was stationed. He stayed with his brother and started looking for a job. At last, after sustained efforts he got a job in the government currency office in the month of February, 1908.

The salary the job paid was thirty rupees a month.

It pleased the family. Now its younger son too was employed although the salary was not much to crow about but it was enough to carry on the business of life. The family could not wait to get him married although Vidyarthi was only 19 years old.

It was the domestic philosophy of the Indian families that a young man needed to be married as soon as possible just like a colt is required to be broken in at right time to turn him into a beast of the family burden lest he should grow wild habits.

Vidyarthi himself didn’t want any marriage so soon. But the family pressure was too strong to resist for long.

On 4th June, 1908 Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi was formally paired with a suitable girl and the marriage was duly solemnised. The young man merrily accepted the responsibilities of his young wife. Now the job had become doubly important for him to sustain the fledgling family.

He performed his duty with devotion and dutifully.

Alongwith the duty he began self studying at home. He told his wife how important it was for him to study to make a headway in life. The young wife understood the need of her husband and cooperatingly allowed him undisturbed time at home.

Vidyarthi appreciated it and was thankful to her for the understanding gesture. It was in the interest of both of them.

Vidyarthi was no more sorry for the disruption of his studies. He realised that the private study was more meaningful and very constructive. He could direct his studies to the subjects he was interested in and learn through his own educational evolution.

Vidyarthi was a natural public relations man. He could easily communicate with others with minimum of the words. It ingratiated him to others. His sweet and polite mannerisms were easy winners. Every body liked him. From a lowly peon to the head clerk all were his dear friends who only derived happiness from him.

But the director of the currency office was an Englishman. He was racial who had very low opinion of native Indians. Infact, he was an open Indian baiter who felt sadistic pleasure in running down Indians.

He lost no opportunity of humiliating the brown or black natives.

Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi had seen that Englishman abuse Indians and torment them in other ways.

It would anger him. But he could do little.

He was himself a lowly rank who had no official power or status besides the fact that he needed the job badly for the sake of his family sustained by the salary it earned.

He would try to avoid the racial Englishman as best as he could.

All the native employees of the office were fed up with the arrogance of the racialist. But like Vidyarthi all of them needed their respective jobs for survival due to poverty and the absence of other opportunities.

One day suddenly that Englishman ran into him when Vidyarthi could not escape his attention having been trapped in a tricky situation.

As a duty Vidyarthi was destroying the old currency notes by burning them. There was a piece of paper lying nearby. It was part of some packing and appeared to be a newspaper piece.

Vidyarthi picked up the paper as a natural reaction. Being education oriented anything printed drew his attention since it should contain some information.

He liked what was written in that paper. He read on and on until he had gleaned the knowledge the article contained. He had not ignored his duty completely. He was casting glances every now and then on the burning lot in between his reading.

It was an article on patriotism and the thoughts impressed him. Vidyarthi himself had a patriotic bend of mind. Deep down in his heart he had grown dislike for the foreign rule over India.

Vidyarthi turned the piece over to know the name of the paper the article was the part of. He found the name on a lined margin. It was a weekly called ‘Karmayogi’—an Allahabad publication.

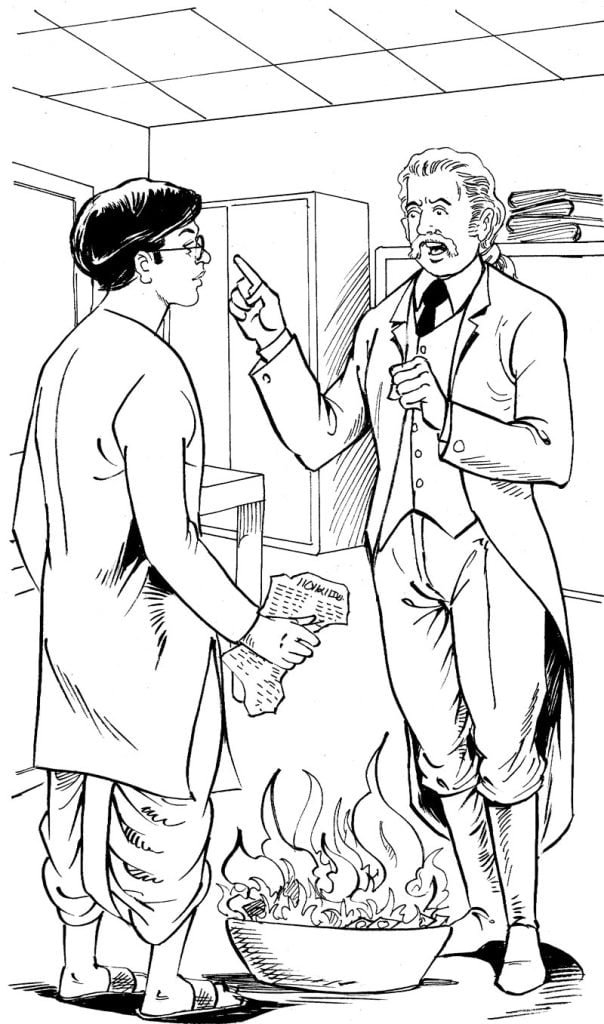

Just as he was staring at the name to confirm it the Indian baitor British officer happened to arrive there. His eyes sparkled just as a policeman’s do when he catches a thief red handed.

The Englishman’s brows arched and he barked, “What are you doing, Hindustani boy?”

Vidyarthi stammered, “Sir, I am burning the condemned currency notes.”

“No, you were not. You were reading that piece of paper. I suspect some anti-government matter.” He was pointing to the piece of the paper Vidyarthi was still holding in his left hand.

“Yes sir,” Vidyarthi admitted and explained, “I was only looking over it. But my whole mind was in the duty of burning notes.”

“You are lying,” the Englishman growled. “You can not befool me.”

“No sir. I am not trying to befool you. I was honestly doing my duty.”

“Honestly indeed! You are not telling the truth. I saw what you were doing with my own eyes. You are not a responsible person, youngman. You deserve to be dismissed, ” the Englishman threatened.

Vidyarthi felt a chill go down his spine.

“I am telling you the truth, sir,” he tried to plead.

The Englishman saw a chance to satisfy his sadistic instincts. The victim was an another Hindustani who was fit for psychological whipping.

He thundered, “You shall be dismissed for cheating on duty.”

He expected the Hindustaini boy to fall at his feet after turning ashen faced at the prospect of becoming jobless and starving to death. He had seen it happen many times before.

He loved to see the wretched Hindustanis crawling like miserable worms around his English boots.

But in the present case no such reaction was forthcoming from Ganesh Shankar. The boy just stood staring at him with some hostility. There was no fear in the eyes of the boy, only a little sadness.

Ganesh Shankar appealed, “I was not cheating sir. My attention was on the job I was doing.

The officer hissed at the Hindustani Ganesh Shankar and marched towards his cabin. Was he going to write dismissal order of Ganesh Shankar for the crime of not falling at Englishman’s feet and begging for mercy, and thus, denying him the sadistic pleasure he was so accustomed to?

Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi stood thinking his next move. He could not accept the humiliation of being served dismissal order for neglect of duty.

Losing job entailed untold financial hardships in Indian conditions. But for Ganesh Shankar saving self-respect and personal dignity was more important.

So, he wrote his resignation letter and marched to the cabin of the English officer. The officer hopefully looked at Vidyarthi expecting him to beg for whiteman’s mercy. But Englishman was not so lucky.

He was handed the letter of resignation by the Hindustani boy. That dismayed the Englishman. It was a jolt to the pride of the whiteman. He thought a Hindustani leaving his service by resigning would not create any good impression among the white fraternity.

Now he wanted to keep the Hindustani in the service to wait for a more suitable opportunity to take his revenge.

He spoke, “Well, have you no family to feed?”

“I have sir…”

“Then, why do you resign?”

“You said that I was going to be dismissed. I thought it better to offer my resignation.”

“I said that as a warning. You must pay attention to your duty and do your work honestly.”

“I was doing my job honestly. I don’t like being accused of dishonesty wrongly,” said Ganesh Shankar and he walked out of the cabin.

He had no intention of taking back the resignation. His mind was made up. The Englishman stared at the resignation letter. Were the cowardly Hindustanis now begun to look into the blue eyes of the white people?

That was a bad news for the colonists.