Chapter 5

Mr. Knightley might quarrel with her, but Emma could not quarrel with herself. He was so much displeased, that it was longer than usual before he came to Hartfield again; and when they did meet, his grave looks shewed that she was not forgiven. She was sorry, but could not repent. On the contrary, her plans and proceedings were more and more justified and endeared to her by the general appearances of the next few days.

The picture, elegantly framed, came safely to hand soon after Mr. Elton’s return, and being hung over the mantelpiece of the common sitting-room, he got up to look at it, and sighed out his half sentences of admiration just as he ought; and as for Harriet’s feelings, they were visibly forming themselves into as strong and steady an attachment as her youth and sort of mind admitted. Emma was soon perfectly satisfied of Mr. Martin’s being no otherwise remembered, than as he furnished a contrast with Mr. Elton, of the utmost advantage to the latter.

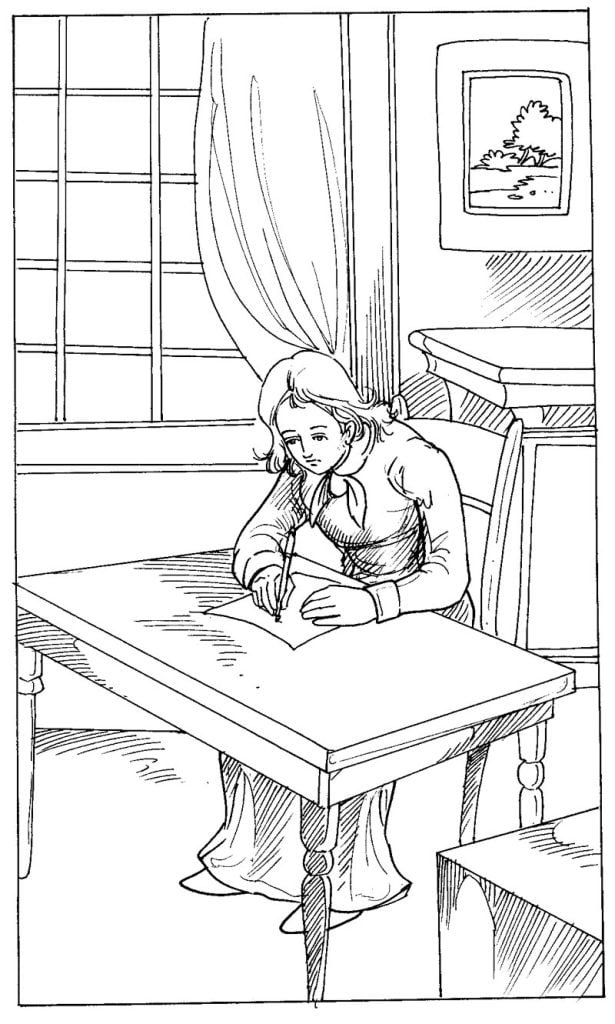

Her views of improving her little friend’s mind, by a great deal of useful reading and conversation, had never yet led to more than a few first chapters, and the intention of going on to-morrow. It was much easier to chat than to study; much pleasanter to let her imagination range and work at Harriet’s fortune, than to be labouring to enlarge her comprehension or exercise it on sober facts; and the only literary pursuit which engaged Harriet at present, the only mental provision she was making for the evening of life, was the collecting and transcribing all the riddles of every sort that she could meet with, into a thin quarto of hot-pressed paper, made up by her friend, and ornamented with ciphers and trophies.

In this age of literature, such collections on a very grand scale are not uncommon. Miss Nash, head-teacher at Mrs. Goddard’s, had written out at least three hundred; and Harriet, who had taken the first hint of it from her, hoped, with Miss Woodhouse’s help, to get a great many more. Emma assisted with her invention, memory and taste; and as Harriet wrote a very pretty hand, it was likely to be an arrangement of the first order, in form as well as quantity.

Mr. Woodhouse was almost as much interested in the business as the girls, and tried very often to recollect something worth their putting in. “So many clever riddles as there used to be when he was young—he wondered he could not remember them! but he hoped he should in time.” And it always ended in ‘Kitty, a fair but frozen maid’.

His good friend Perry, too, whom he had spoken to on the subject, did not at present recollect any thing of the riddle kind; but he had desired Perry to be upon the watch, and as he went about so much, something, he thought, might come from that quarter.

Though now the middle of December, there had yet been no weather to prevent the young ladies from tolerably regular exercise; and on the morrow, Emma had a charitable visit to pay to a poor sick family, who lived a little way out of Highbury.

Their road to this detached cottage was down Vicarage Lane, a lane leading at right angles from the broad, though irregular, main street of the place; and, as may be inferred, containing the blessed abode of Mr. Elton. A few inferior dwellings were first to be passed, and then, about a quarter of a mile down the lane rose the Vicarage, an old and not very good house, almost as close to the road as it could be. It had no advantage of situation; but had been very much smartened up by the present proprietor; and, such as it was, there could be no possibility of the two friends passing it without a slackened pace and observing eyes. Emma’s remark was—“There it is. There go you and your riddle-book one of these days.” Harriet’s was—“Oh, what a sweet house! How very beautiful! There are the yellow curtains that Miss Nash admires so much.”

“I do not often walk this way now,” said Emma, as they proceeded, “but then there will be an inducement, and I shall gradually get intimately acquainted with all the hedges, gates, pools and pollards of this part of Highbury.”

Harriet, she found, had never in her life been within side the Vicarage, and her curiosity to see it was so extreme, that, considering exteriors and probabilities, Emma could only class it, as a proof of love, with Mr. Elton’s seeing ready wit in her.

“I wish we could contrive it,” said she, “but I cannot think of any tolerable pretence for going in; no servant that I want to inquire about of his housekeeper—no message from my father.”

She pondered, but could think of nothing. After a mutual silence of some minutes, Harriet thus began again, “I do so wonder, Miss Woodhouse, that you should not be married, or going to be married! so charming as you are!”

Emma laughed, and replied,

“My being charming, Harriet, is not quite enough to induce me to marry; I must find other people charming— one other person at least. And I am not only, not going to be married, at present, but have very little intention of ever marrying at all.”

“Ah!—so you say; but I cannot believe it.”

“I must see somebody very superior to any one I have seen yet, to be tempted; Mr. Elton, you know, (recollecting herself,) is out of the question: and I do not wish to see any such person. I would rather not be tempted. I cannot really change for the better. If I were to marry, I must expect to repent it.”

“Dear me! it is so odd to hear a woman talk so!”

“I have none of the usual inducements of women to marry. Were I to fall in love, indeed, it would be a different thing! but I never have been in love; it is not my way, or my nature; and I do not think I ever shall. And, without love, I am sure I should be a fool to change such a situation as mine. Fortune I do not want; employment I do not want; consequence I do not want: I believe few married women are half as much mistress of their husband’s house as I am of Hartfield; and never, never could I expect to be so truly beloved and important; so always first and always right in any man’s eyes as I am in my father’s.”

“But then, to be an old maid at last, like Miss Bates!”

“That is as formidable an image as you could present, Harriet; and if I thought I should ever be like Miss Bates! so silly—so satisfied— so smiling—so prosing—so undistinguishing and unfastidious— and so apt to tell everything relative to everybody about me, I would marry to-morrow. But between us, I am convinced there never can be any likeness, except in being unmarried.”

“But still, you will be an old maid! and that’s so dreadful!”