Chapter 9

The few words which Marguerite Blakeney had managed to read on the half-scorched piece of paper, seemed literally to be the words of Fate. “Start myself tomorrow.” This she had read quite distinctly; then came a blur caused by the smoke of the candle, which obliterated the next few words; but, right at the bottom, there was another sentence, like letters of fire, before her mental vision, “If you wish to speak to me again I shall be in the supper-room at one o’clock precisely.” The whole was signed with the hastily-scrawled little device—a tiny star-shaped flower, which had become so familiar to her.

One o’clock precisely! It was now close upon eleven, the last minuet was being danced, with Sir Andrew Ffoulkes and beautiful Lady Blakeney leading the couples, through its delicate and intricate figures.

Close upon eleven! the hands of the handsome Louis XV clock upon its ormolu bracket seemed to move along with maddening rapidity. Two hours more, and her fate and that of Armand would be sealed. In two hours she must make up her mind whether she will keep the knowledge so cunningly gained to herself, and leave her brother to his fate, or whether she will wilfully betray a brave man, whose life was devoted to his fellow-men, who was noble, generous, and above all, unsuspecting. It seemed a horrible thing to do. But then, there was Armand! Armand, too, was noble and brave, Armand, too, was unsuspecting. And Armand loved her, would have willingly trusted his life in her hands, and now, when she could save him from death, she hesitated. Oh! it was monstrous; her brother’s kind, gentle face, so full of love for her, seemed to be looking reproachfully at her. “You might have saved me, Margot!” he seemed to say to her, “and you chose the life of a stranger, a man you do not know, whom you have never seen, and preferred that he should be safe, whilst you sent me to the guillotine!”

All these conflicting thoughts raged through Marguerite’s brain, while, with a smile upon her lips, she glided through the graceful mazes of the minuet. She noted—with that acute sense of hers—that she had succeeded in completely allaying Sir Andrew’s fears. Her self-control had been absolutely perfect—she was a finer actress at this moment, and throughout the whole of this minuet, than she had ever been upon the boards of the Comedie Francaise; but then, a beloved brother’s life had not depended upon her histrionic powers.

She was too clever to overdo her part, and made no further allusions to the supposed BILLET DOUX, which had caused Sir Andrew Ffoulkes such an agonising five minutes. She watched his anxiety melting away under her sunny smile, and soon perceived that, whatever doubt may have crossed his mind at the moment, she had, by the time the last bars of the minuet had been played, succeeded in completely dispelling it; he never realised in what a fever of excitement she was, what effort it cost her to keep up a constant ripple of BANAL conversation.

When the minuet was over, she asked Sir Andrew to take her into the next room.

“I have promised to go down to supper with His Royal Highness,” she said, “but before we part, tell me. Am I forgiven?”

“Forgiven?”

“Yes! Confess, I gave you a fright just now. . . . But remember, I am not an English woman, and I do not look upon the exchanging of BILLET DOUX as a crime, and I vow I’ll not tell my little Suzanne. But now, tell me, shall I welcome you at my water-party on Wednesday?”

“I am not sure, Lady Blakeney,” he replied evasively. “I may have to leave London to-morrow.”

“I would not do that, if I were you,” she said earnestly; then seeing the anxious look reappearing in his eyes, she added gaily; “No one can throw a ball better than you can, Sir Andrew, we should so miss you on the bowling-green.”

He had led her across the room, to one beyond, where already His Royal Highness was waiting for the beautiful Lady Blakeney.

“Madame, supper awaits us,” said the Prince, offering his arm to Marguerite, “and I am full of hope. The goddess Fortune has frowned so persistently on me at hazard, that I look with confidence for the smiles of the goddess of Beauty.”

“Your Highness has been unfortunate at the card tables?” asked Marguerite, as she took the Prince’s arm.

“Aye! most unfortunate. Blakeney, not content with being the richest among my father’s subjects, has also the most outrageous luck. By the way, where is that inimitable wit? I vow, Madam, that this life would be but a dreary desert without your smiles and his sallies.”

Supper had been extremely gay. All those present declared that never had Lady Blakeney been more adorable, nor that ‘demmed idiot’ Sir Percy more amusing. Marguerite Blakeney was in her most brilliant mood, and surely not a soul in that crowded supper-room had even an inkling of the terrible struggle which was raging within her heart.

The clock was ticking so mercilessly on. It was long past midnight, and even the Prince of Wales was thinking of leaving the supper-table. Within the next half-hour the destinies of two brave men would be pitted against one another—the dearly-beloved brother and he, the unknown hero.

Marguerite had not tried to see Chauvelin during this last hour; she knew that his keen, fox-like eyes would terrify her at once, and incline the balance of her decision towards Armand. Whilst she did not see him, there still lingered in her heart of hearts a vague, undefined hope that ‘something’ would occur, something big, enormous, epoch-making, which would shift from her young, weak shoulders this terrible burden of responsibility, of having to choose between two such cruel alternatives.

But the minutes ticked on with that dull monotony which they invariably seem to assume when our very nerves ache with their incessant ticking.

After supper, dancing was resumed. His Royal Highness had left, and there was general talk of departing among the older guests; the young were indefatigable and had started on a new gavotte, which would fill the next quarter of an hour.

Perhaps—vaguely—Marguerite hoped that the daring plotter, who for so many months had baffled an army of spies, would still manage to evade Chauvelin and remain immune to the end.

She thought of all this, as she sat listening to the witty discourse of the Cabinet Minister, who, no doubt, felt that he had found in Lady Blakeney a most perfect listener. Suddenly she saw the keen, fox-like face of Chauvelin peeping through the curtained doorway.

“Lord Fancourt,” she said to the Minister, “will you do me a service?”

“I am entirely at your ladyship’s service,” he replied gallantly.

“Will you see if my husband is still in the card-room? And if he is, will you tell him that I am very tired, and would be glad to go home soon.”

The commands of a beautiful woman are binding on all mankind, even on Cabinet Ministers. Lord Fancourt prepared to obey instantly.

“I do not like to leave your ladyship alone,” he said.

“Never fear. I shall be quite safe here—and, I think, undisturbed. . .but I am really tired. You know Sir Percy will drive back to Richmond. It is a long way, and we shall not—an we do not hurry—get home before daybreak.”

Lord Fancourt had perforce to go.

The moment he had disappeared, Chauvelin slipped into the room, and the next instant stood calm and impassive by her side.

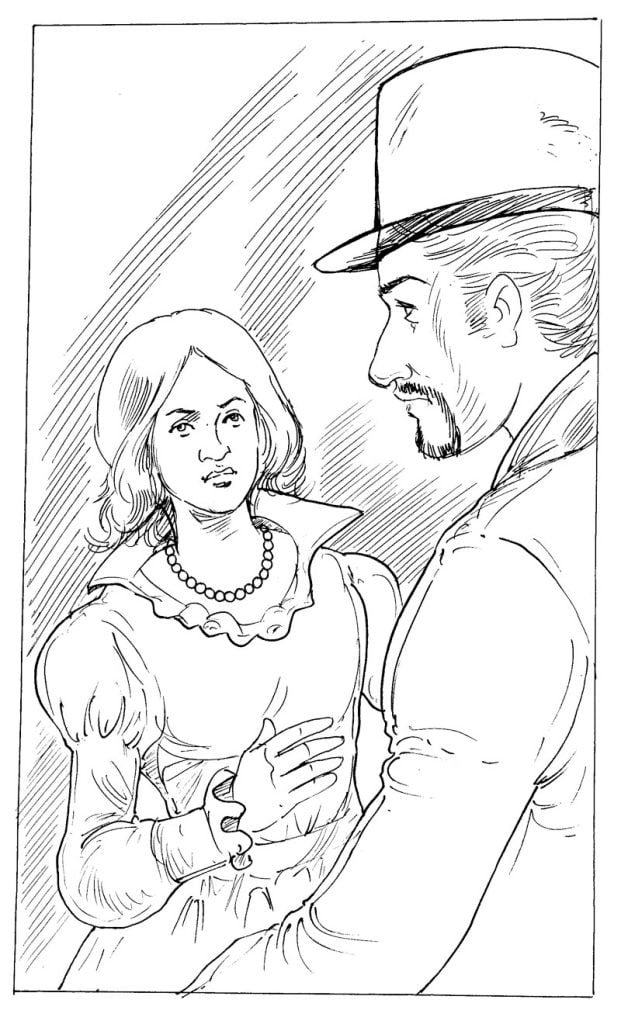

“You have news for me?” he said.

An icy mantle seemed to have suddenly settled round Marguerite’s shoulders; though her cheeks glowed with fire, she felt chilled and numbed. Oh, Armand! will you ever know the terrible sacrifice of pride, of dignity, of womanliness a devoted sister is making for your sake?

“Nothing of importance,” she said, staring mechanically before her, “but it might prove a clue. I contrived—no matter how—to detect Sir Andrew Ffoulkes in the very act of burning a paper at one of these candles, in this very room. That paper I succeeded in holding between my fingers for the space of two minutes, and to cast my eyes on it for that of ten seconds.”

“Time enough to learn its contents?” asked Chauvelin, quietly.

She nodded. Then continued in the same even, mechanical tone of voice—“In the corner of the paper there was the usual rough device of a small star-shaped flower. Above it I read two lines, everything else was scorched and blackened by the flame.”

“And what were the two lines?”

Her throat seemed suddenly to have contracted. For an instant she felt that she could not speak the words, which might send a brave man to his death.

“It is lucky that the whole paper was not burned,” added Chauvelin, with dry sarcasm, “for it might have fared ill with Armand St. Just. What were the two lines citoyenne?”

“One was, I start myself to-morrow,” she said quietly, “the other—‘If you wish to speak to me, I shall be in the supper-room at one o’clock precisely’.”

Chauvelin looked up at the clock just above the mantelpiece.

“Then I have plenty of time,” he said placidly.

“What are you going to do?” she asked.

“What are you going to do?” she repeated mechanically.

“Oh, nothing for the present. After that it will depend.”

“On what?”

“On whom I shall see in the supper-room at one o’clock precisely.”

“You will see the Scarlet Pimpernel, of course. But you do not know him.”

“No. But I shall presently.”

“Sir Andrew will have warned him.”

He was preparing to go, and went up to the doorway where, drawing aside the curtain, he stood for a moment pointing out to Marguerite the distant figure of Sir Andrew Ffoulkes in close conversation with Lady Portarles.

“I think,” he said, with a triumphant smile, “that I may safely expect to find the person I seek in the dining-room, fair lady.”

“There may be more than one.”

“Whoever is there, as the clock strikes one, will be shadowed by one of my men; of these, one, or perhaps two, or even three, will leave for France to-morrow. ONE of these will be ‘the Scarlet Pimpernel’.”

“Yes?—And?”

“I also, fair lady, will leave for France to-morrow. The papers found at Dover upon the person of Sir Andrew Ffoulkes speak of the neighborhood of Calais, of an inn which I know well, called ‘Le Chat Gris,’ of a lonely place somewhere on the coast—the Pere Blanchard’s hut—which I must endeavor to find. All these places are given as the point where this meddlesome Englishman has bidden the traitor de Tournay and others to meet his emissaries. But it seems that he has decided not to send his emissaries, that ‘he will start himself to-morrow.’

Now, one of these persons whom I shall see anon in the supper-room, will be journeying to Calais, and I shall follow that person, until I have tracked him to where those fugitive aristocrats await him; for that person, fair lady, will be the man whom I have sought for, for nearly a year, the man whose energies has outdone me, whose ingenuity has baffled me, whose audacity has set me wondering—yes! me!—who have seen a trick or two in my time—the mysterious and elusive Scarlet Pimpernel.”

“And Armand?” she pleaded.

“Have I ever broken my word? I promise you that the day the Scarlet Pimpernel and I start for France, I will send you that imprudent letter of his by special courier. More than that, I will pledge you the word of France, that the day I lay hands on that meddlesome Englishman, St. Just will be here in England, safe in the arms of his charming sister.”

And with a deep and elaborate bow and another look at the clock, Chauvelin glided out of the room.

When Chauvelin reached the supper-room it was quite deserted. It had that woebegone, forsaken, tawdry appearance, which reminds one so much of a ball-dress, the morning after.

No wonder that in France the sobriquet of the mysterious Englishman roused in the people a superstitious shudder. Chauvelin himself as he gazed round the deserted room, where presently the weird hero would appear, felt a strange feeling of awe creeping all down his spine.

But his plans were well laid. He felt sure that the Scarlet Pimpernel had not been warned, and felt equally sure that Marguerite Blakeney had not played him false. If she had a cruel look, that would have made her shudder, gleamed in Chauvelin’s keen, pale eyes. If she had played him a trick, Armand St. Just would suffer the extreme penalty.

But no, no! of course she had not played him false!

Fortunately the supper-room was deserted. This would make Chauvelin’s task all the easier, when presently that unsuspecting enigma would enter it alone. No one was here now save Chauvelin himself.

Stay! as he surveyed with a satisfied smile the solitude of the room, the cunning agent of the French Government became aware of the peaceful, monotonous breathing of some one of my Lord Grenville’s guests, who, no doubt, had supped both wisely and well, and was enjoying a quiet sleep, away from the din of the dancing above.

Chauvelin looked round once more, and there in the corner of a sofa, in the dark angle of the room, his mouth open, his eyes shut, the sweet sounds of peaceful slumbers proceedings from his nostrils, reclined the gorgeously-apparelled, long-limbed husband of the cleverest woman in Europe.

Chauvelin looked at him as he lay there, placid, unconscious, at peace with all the world and himself, after the best of suppers, and a smile, that was almost one of pity, softened for a moment the hard lines of the Frenchman’s face and the sarcastic twinkle of his pale eyes.

Evidently the slumberer, deep in dreamless sleep, would not interfere with Chauvelin’s trap for catching that cunning Scarlet Pimpernel. Again he rubbed his hands together, and, following the example of Sir Percy Blakeney, he too, stretched himself out in the corner of another sofa, shut his eyes, opened his mouth, gave forth sounds of peaceful breathing, and waited!

Marguerite Blakeney had watched the slight sable-clad figure of Chauvelin, as he worked his way through the ball-room. Then perforce she had had to wait, while her nerves tingled with excitement. Listlessly she sat in the small, still deserted boudoir, looking out through the curtained doorway on the dancing couples beyond: looking at them, yet seeing nothing, hearing the music, yet conscious of naught save a feeling of expectancy, of anxious, weary waiting.

Her mind conjured up before her the vision of what was, perhaps at this very moment, passing downstairs. The half-deserted dining-room, the fateful hour—Chauvelin on the watch!—then, precise to the moment, the entrance of a man, he, the Scarlet Pimpernel, the mysterious leader, who to Marguerite had become almost unreal, so strange, so weird was this hidden identity.

She wished she were in the supper-room, too, at this moment, watching him as he entered; she knew that her woman’s penetration would at once recognise in the stranger’s face—whoever he might be—that strong individuality which belongs to a leader of men—to a hero: to the mighty, high-soaring eagle, whose daring wings were becoming entangled in the ferret’s trap.

Woman-like, she thought of him with unmixed sadness; the irony of that fate seemed so cruel which allowed the fearless lion to succumb to the gnawing of a rat! Ah! had Armand’s life not been at stake!. . .

“Faith! your ladyship must have thought me very remiss,” said a voice suddenly, close to her elbow. “I had a deal of difficulty in delivering your message, for I could not find Blakeney anywhere at first.”

Marguerite had forgotten all about her husband and her message to him; his very name, as spoken by Lord Fancourt, sounded strange and unfamiliar to her, so completely had she in the last five minutes lived her old life in the Rue de Richelieu again, with Armand always near her to love and protect her, to guard her from the many subtle intrigues which were forever raging in Paris in those days.

“I did find him at last,” continued Lord Fancourt, “and gave him your message. He said that he would give orders at once for the horses to be put to.”

“Ah!” she said, still very absently, “you found my husband, and gave him my message?”

“Yes; he was in the dining-room fast asleep. I could not manage to wake him up at first.”

“Thank you very much,” she said mechanically, trying to collect her thoughts.

“Will your ladyship honour me with the Contredanse until your coach is ready?” asked Lord Fancourt.

“No, I thank you, my lord, but—and you will forgive me—I really am too tired, and the heat in the ball-room has become oppressive.”

“The conservatory is deliciously cool; let me take you there, and then get you something. You seem ailing, Lady Blakeney.”

“I am only very tired,” she repeated wearily, as she allowed Lord Fancourt to lead her, where subdued lights and green plants lent coolness to the air. He got her a chair, into which she sank. This long interval of waiting was intolerable. Why did not Chauvelin come and tell her the result of his watch?

Lord Fancourt was very attentive. She scarcely heard what he said, and suddenly startled him by asking abruptly, “Lord Fancourt, did you perceive who was in the dining-room just now besides Sir Percy Blakeney?”

“Only the agent of the French government, M. Chauvelin, equally fast asleep in another corner,” he said. “Why does your ladyship ask?”

“I know not. Did you notice the time when you were there?”

“It must have been about five or ten minutes past one. I wonder what your ladyship is thinking about,” he added, for evidently the fair lady’s thoughts were very far away, and she had not been listening to his intellectual conversation.

Lord Fancourt had given up talking since he found that he had no listener. He wanted an opportunity for slipping away; for sitting opposite to a lady, however fair, who is evidently not heeding the most vigorous efforts made for her entertainment, is not exhilarating, even to a Cabinet Minister.

“Shall I find out if your ladyship’s coach is ready,” he said at last, tentatively.

“Oh, thank you. . .thank you. . .if you would be so kind. I fear I am but sorry company. . .but I am really tired and, perhaps, would be best alone.

He had pronounced his “Either—or—” and nothing less would content him: he was very spiteful, and would affect the belief that she had wilfully misled him, and having failed to trap the eagle once again, his revengeful mind would be content with the humble prey—Armand! Yet she had done her best; had strained every nerve for Armand’s sake. She could not bear to think that all had failed. She could not sit still; she wanted to go and hear the worst at once; she wondered even that Chauvelin had not come yet, to vent his wrath and satire upon her.

Lord Grenville himself came presently to tell her that her coach was ready, and that Sir Percy was already waiting for her—ribbons in hand. Marguerite said “Farewell” to her distinguished host; many of her friends stopped her, as she crossed the rooms, to talk to her, and exchange pleasant AU REVOIRS.

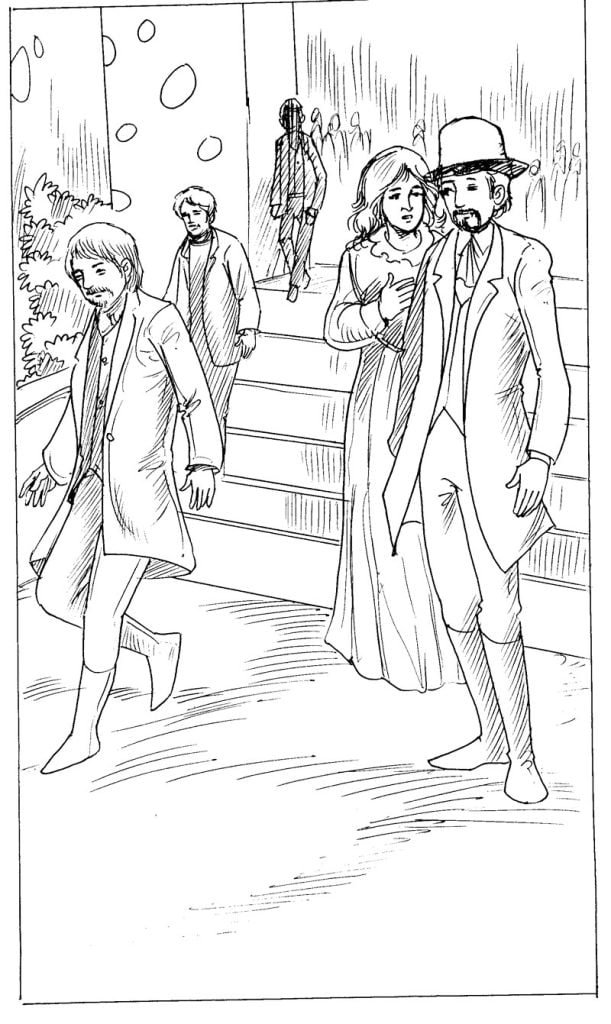

The Minister only took final leave of beautiful Lady Blakeney on the top of the stairs; below, on the landing, a veritable army of gallant gentlemen were waiting to bid “Good-bye” to the queen of beauty and fashion, whilst outside, under the massive portico, Sir Percy’s magnificent bays were impatient pawing the ground.

At the top of the stairs, just after she had taken final leave of her host, she suddenly say Chauvelin; he was coming up the stairs slowly, and rubbing his thin hands very softly together.

There was a curious look on his mobile face, partly amused and wholly puzzled, as his keen eyes met Marguerite’s they became strangely sarcastic.

“M. Chauvelin,” she said, as he stopped on the top of the stairs, bowing elaborately before her, “my coach is outside; may I claim your arm?”

As gallant as ever, he offered her his arm and led her downstairs. The crowd was very great, some of the Minister’s guests were departing, others were leaning against the banisters watching the throng as it filed up and down the wide staircase.

“Chauvelin,” she said at last desperately, “I must know what has happened.”

“What has happened, dear lady?” he said, with affected surprise. “Where? When?”

“You are torturing me, Chauvelin. I have helped you to-night. Surely I have the right to know. What happened in the dining-room at one o’clock just now?”

She spoke in a whisper, trusting that in the general hubbub of the crowd her words would remain unheeded by all, save the man at her side.

“Quiet and peace reigned supreme, fair lady; at that hour I was asleep in one corner of one sofa and Sir Percy Blakeney in another.”

“Nobody came into the room at all?”

“Nobody.”

“Then we have failed, you and I?”

“Yes! we have failed—perhaps.”

“But Armand?” she pleaded.

“Ah! Armand St. Just’s chances hang on a thread pray heaven, dear lady, that that thread may not snap.”

“Chauvelin, I worked for you, sincerely, earnestly. Remember.”

“I remember my promise,” he said quietly. “The day that the Scarlet Pimpernel and I meet on French soil, St. Just will be in the arms of his charming sister.”

“Which means that a brave man’s blood will be on my hands,” she said, with a shudder.

“His blood, or that of your brother. Surely at the present moment you must hope, as I do, that the enigmatical Scarlet Pimpernel will start for Calais to-day.”

“I am only conscious of one hope, citoyen.”

“And that is?”

“That Satan, your master, will have need of you elsewhere, before the sun rises to-day.”

“You flatter me, citoyenne.”

She had detained him for a while, mid-way down the stairs, trying to get at the thoughts which lay beyond that thin, fox-like mask. But Chauvelin remained urbane, sarcastic, mysterious; not a line betrayed to the poor, anxious woman whether she need fear or whether she dared to hope.

Downstairs on the landing she was soon surrounded. Lady Blakeney never stepped from any house into her coach, without an escort of fluttering human moths around the dazzling light of her beauty. But before she finally turned away from Chauvelin, she held out a tiny hand to him, with that pretty gesture of childish appeal which was essentially her own. “Give me some hope, my little Chauvelin,” she pleaded.

With perfect gallantry he bowed over that tiny hand, which looked so dainty and white through the delicately transparent black lace mitten, and kissing the tips of the rosy fingers:—“Pray heaven that the thread may not snap,” he repeated, with his enigmatic smile.

And stepping aside, he allowed the moths to flutter more closely round the candle, and the brilliant throng of the JEUNESSE DOREE, eagerly attentive to Lady Blakeney’s every movement, hid the keen, fox-like face from her view.

A few minutes later she was sitting, wrapped in cozy furs, near Sir Percy Blakeney on the box-seat of his magnificent coach, and the four splendid bays had thundered down the quiet street.

The night was warm in spite of the gentle breeze which fanned Marguerite’s burning cheeks. Soon London houses were left behind, and rattling over old Hammersmith Bridge. Sir Percy was driving his bays rapidly towards Richmond.

The river wound in and out in its pretty delicate curves, looking like a silver serpent beneath the glittering rays of the moon. Long shadows from overhanging trees spread occasional deep palls right across the road. The bays were rushing along at breakneck speed, held but slightly back by Sir Percy’s strong, unerring hands.

To-night he seemed to have a very devil in his fingers, and the coach seemed to fly along the road, beside the river. As usual, he did not speak to her, but stared straight in front of him, the ribbons seeming to lie quite loosely in his slender, white hands. Marguerite looked at him tentatively once or twice; she could see his handsome profile, and one lazy eye, with its straight fine brow and drooping heavy lid.

The face in the moonlight looked singularly earnest, and recalled to Marguerite’s aching heart those happy days of courtship, before he had become the lazy nincompoop, the effete fop, whose life seemed spent in card and supper rooms.

Marguerite suddenly felt intense sympathy for her husband. The moral crisis she had just gone through made her feel indulgent towards the faults, the delinquencies, of others.

How thoroughly a human being can be buffeted and overmastered by Fate, had been borne in upon her with appalling force. Had anyone told her a week ago that she would stoop to spy upon her friends, that she would betray a brave and unsuspecting man into the hands of a relentless enemy, she would have laughed the idea to scorn.

Yet she had done these things; anon, perhaps the death of that brave man would be at her door, just as two years ago the Marquis de St. Cyr had perished through a thoughtless words of hers; but in that case she was morally innocent—she had meant no serious harm—fate merely had stepped in. But this time she had done a thing that obviously was base, had done it deliberately, for a motive which, perhaps, high moralists would not even appreciate.

Buried in her thoughts, Marguerite had found this hour in the breezy summer night all too brief; and it was with a feeling of keen disappointment, that she suddenly realised that the bays had turned into the massive gates of her beautiful English home.

Sir Percy Blakeney’s house on the river has become a historic one: palatial in its dimensions, it stands in the midst of exquisitely laid-out gardens, with a picturesque terrace and frontage to the river. Built in Tudor days, the old red brick of the walls looks eminently picturesque in the midst of a bower of green, the beautiful lawn, with its old sun-dial, adding the true note of harmony to its foregrounds, and now, on this warm early autumn night, the leaves slightly turned to russets and gold, the old garden looked singularly poetic and peaceful in the moonlight.

With unerring precision, Sir Percy had brought the four bays to a standstill immediately in front of the fine Elizabethan entrance hall; in spite of the late hour, an army of grooms seemed to have emerged from the very ground, as the coach had thundered up, and were standing respectfully round.

All else was quiet round her. She had heard the horses prancing as they were being led away to their distant stables, the hurrying of servant’s feet as they had all gone within to rest: the house also was quite still. In two separate suites of apartments, just above the magnificent reception-rooms, lights were still burning, they were her rooms, and his, well divided from each other by the whole width of the house, as far apart as their own lives had become. Involuntarily she sighed—at that moment she could really not have told why.

She was suffering from unconquerable heartache. Deeply and achingly she was sorry for herself. Never had she felt so pitiably lonely, so bitterly in want of comfort and of sympathy. With another sigh she turned away from the river towards the house, vaguely wondering if, after such a night, she could ever find rest and sleep.

He apparently did not notice her, for, after a few moments pause, he presently turned back towards the house, and walked straight up to the terrace.

“Sir Percy!”

He already had one foot on the lowest of the terrace steps, but at her voice he started, and paused, then looked searchingly into the shadows whence she had called to him. She came forward quickly into the moonlight, and, as soon as he saw her, he said, with that air of consummate gallantry he always wore when speaking to her, “At your service, Madame!”

But his foot was still on the step, and in his whole attitude there was a remote suggestion, distinctly visible to her, that he wished to go, and had no desire for a midnight interview.

“The air is deliciously cool,” she said, “the moonlight peaceful and poetic, and the garden inviting. Will you not stay in it awhile; the hour is not yet late, or is my company so distasteful to you, that you are in a hurry to rid yourself of it?”

“Nay, Madame,” he rejoined placidly, “but tis on the other foot the shoe happens to be, and I’ll warrant you’ll find the midnight air more poetic without my company: no doubt the sooner I remove the obstruction the better your ladyship will like it.”

He turned once more to go.

“I protest you mistake me, Sir Percy,” she said hurriedly, and drawing a little closer to him; “the estrangement, which alas! has arisen between us, was none of my making, remember.”

“Begad! you must pardon me there, Madame!” he protested coldly, “my memory was always of the shortest.”

He looked her straight in the eyes, with that lazy non-chalance which had become second nature to him. She returned his gaze for a moment, then her eyes softened, as she came up quite close to him, to the foot of the terrace steps.

“Of the shortest, Sir Percy! Faith! how it must have altered! Was it three years ago or four that you saw me for one hour in Paris, on your way to the East? When you came back two years later you had not forgotten me.”

She looked divinely pretty as she stood there in the moonlight, with the fur-cloak sliding off her beautiful shoulders, the gold embroidery on her dress shimmering around her, her childlike blue eyes turned up fully at him.

He stood for a moment, rigid and still, but for the clenching of his hand against the stone balustrade of the terrace.

“You desired my presence, Madame,” he said frigidly. “I take it that it was not with the view to indulging in tender reminiscences.”

“Nay, Sir Percy, why not? the present is not so glorious but that I should not wish to dwell a little in the past.”

He bent his tall figure, and taking hold of the extreme tip of the fingers which she still held out to him, he kissed them ceremoniously.

“I’ faith, Madame,” he said, “then you will pardon me, if my dull wits cannot accompany you there.”

Once again he attempted to go, once more her voice, sweet, childlike, almost tender, called him back.

“Sir Percy.”

“Your servant, Madame.”

“Is it possible that love can die?” she said with sudden, unreasoning vehemence. “I thought that the passion which you once felt for me would outlast the span of human life. Is there nothing left of that love, Percy, which might help you to bridge over that sad estrangement?”

His massive figure seemed, while she spoke thus to him, to stiffen still more, the strong mouth hardened, a look of relentless obstinacy crept into the habitually lazy blue eyes.

“With what object, I pray you, Madame?” he asked coldly.

“I do not understand you.”

“Yet tis simple enough,” he said with sudden bitterness, which seemed literally to surge through his words, though he was making visible efforts to suppress it, “I humbly put the question to you, for my slow wits are unable to grasp the cause of this, your ladyship’s sudden new mood. Is it that you have the taste to renew the devilish sport which you played so successfully last year? Do you wish to see me once more a love-sick suppliant at your feet, so that you might again have the pleasure of kicking me aside, like a troublesome lap-dog?”

She had succeeded in rousing him for the moment: and again she looked straight at him, for it was thus she remembered him a year ago.

“Percy! I entreat you!” she whispered, “can we not bury the past?”

“Pardon me, Madame, but I understood you to say that your desire was to dwell in it.”

“Nay! I spoke not of that past, Percy!” she said, while a tone of tenderness crept into her voice. “Rather did I speak of a time when you loved me still! and I. . .oh! I was vain and frivolous; your wealth and position allured me: I married you, hoping in my heart that your great love for me would beget in me a love for you but, alas!”

The moon had sunk low down behind a bank of clouds. In the east a soft grey light was beginning to chase away the heavy mantle of the night. He could only see her graceful outline now, the small queenly head, with its wealth of reddish golden curls, and the glittering gems forming the small, star-shaped, red flower which she wore as a diadem in her hair.

“Twenty-four hours after our marriage, Madame, the Marquis de St. Cyr and all his family perished on the guillotine, and the popular rumour reached me that it was the wife of Sir Percy Blakeney who helped to send them there.”

“Nay! I myself told you the truth of that odious tale.”

“Not till after it had been recounted to me by strangers, with all its horrible details.”

Marguerite Blakeney was, above all, a woman, with all a woman’s fascinating foibles, all a woman’s most lovable sins. She knew in a moment that for the past few months she had been mistaken: that this man who stood here before her, cold as a statue, when her musical voice struck upon his ear, loved her, as he had loved her a year ago: that his passion might have been dormant, but that it was there, as strong, as intense, as overwhelming, as when first her lips met his in one long, maddening kiss. Pride had kept him from her, and, woman-like, she meant to win back that conquest which had been hers before. Suddenly it seemed to her that the only happiness life could every hold for her again would be in feeling that man’s kiss once more upon her lips.

“It is perhaps a little difficult, Madame,” said Sir Percy, after a moment of silence between them, “to go back over the past. I have confessed to you that my memory is short, but the thought certainly lingered in my mind that, at the time of the Marquis’ death, I entreated you for an explanation of those same noisome popular rumours.

If that same memory does not, even now, play me a trick, I fancy that you refused me ALL explanation then, and demanded of my love a humiliating allegiance it was not prepared to give.”

“I wished to test your love for me, and it did not bear the test. You used to tell me that you drew the very breath of life but for me, and for love of me.”

She need not complain now that he was cold and impassive; his very voice shook with an intensity of passion, which he was making superhuman efforts to keep in check.

“Aye! the madness of my pride!” she said sadly. “Hardly had I gone, already I had repented. But when I returned, I found you, oh, so altered! wearing already that mask of somnolent indifference which you have never laid aside until now.”

“Nay, Madame, it is no mask,” he said icily; “I swore to you once, that my life was yours. For months now it has been your plaything; it has served its purpose.”

But now she knew that the very coldness was a mask. The trouble, the sorrow she had gone through last night, suddenly came back into her mind, but no longer with bitterness, rather with a feeling that this man who loved her, would help her bear the burden.

“Sir Percy,” she said impulsively, “Heaven knows you have been at pains to make the task, which I had set to myself, difficult to accomplish. You spoke of my mood just now; well! we will call it that, if you will. I wished to speak to you because I was in trouble and had need of your sympathy.”

“It is yours to command, Madame.”

“How cold you are!” she sighed. “Faith! I can scarce believe that but a few months ago one tear in my eye had set you well-nigh crazy. Now I come to you with a half-broken heart.”

“I pray you, Madame,” he said, whilst his voice shook almost as much as hers, “in what way can I serve you?”

“Percy!—Armand is in deadly danger. A letter of his—rash, impetuous, as were all his actions, and written to Sir Andrew Ffoulkes, has fallen into the hands of a fanatic. Armand is hopelessly compromised to-morrow, perhaps he will be arrested. It is horrible!” she said, with a sudden wail of anguish, as all the events of the past night came rushing back to her mind, “horrible! and you do not understand; you cannot. And I have no one to whom I can turn for help or even for sympathy.”

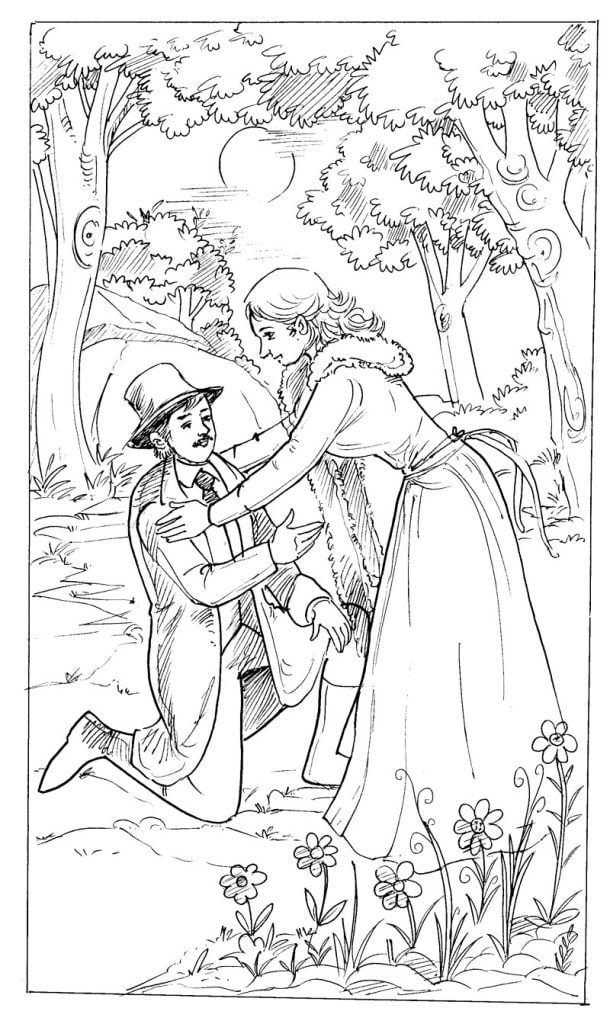

Tears now refused to be held back. All her trouble, her struggles, the awful uncertainty of Armand’s fate overwhelmed her. She tottered, ready to fall, and leaning against the tone balustrade, she buried her face in her hands and sobbed bitterly.

“And so,” he said with bitter sarcasm, “the murderous dog of the revolution is turning upon the very hands that fed it? Begad, Madame,” he added very gently, as Marguerite continued to sob hysterically, “will you dry your tears?. . .I never could bear to see a pretty woman cry, and I.”

Instinctively, with sudden overmastering passion at the sight of her helplessness and of her grief, he stretched out his arms, and the next, would have seized her and held her to him, protected from every evil with his very life, his very heart’s blood. But pride had the better of it in this struggle once again; he restrained himself with a tremendous effort of will, and said coldly, though still very gently, “Will you not turn to me, Madame, and tell me in what way I may have the honour to serve you?”

She made a violent effort to control herself, and turning her tear-stained face to him, she once more held out her hand, which he kissed with the same punctilious gallantry; but Marguerite’s fingers, this time, lingered in his hand for a second or two longer than was absolutely necessary, and this was because she had felt that his hand trembled perceptibly and was burning hot, whilst his lips felt as cold as marble.

“Can you do aught for Armand?” she said sweetly and simply. “You have so much influence at court, so many friends.”

“Nay, Madame, should you not seek the influence of your French friend, M. Chauvelin? His extends, if I mistake not, even as far as the Republican Government of France.”

“I cannot ask him, Percy. Oh! I wish I dared to tell you but he has put a price on my brother’s head.”

“You will at least accept my gratitude?” she said, as she drew quite close to him, and speaking with real tenderness.

With a quick, almost involuntary effort he would have taken her then in his arms, for her eyes were swimming in tears, which he longed to kiss away; but she had lured him once, just like this, then cast him aside like an ill-fitting glove. He thought this was but a mood, a caprice, and he was too proud to lend himself to it once again.

“It is too soon, Madame!” he said quietly; “I have done nothing as yet. The hour is late, and you must be fatigued. Your women will be waiting for you upstairs.”

lay a strong, impassable barrier, built up of pride on both sides, which neither of them cared to be the first to demolish.

He had bent his tall figure in a low ceremonious bow, as she finally, with another bitter little sigh, began to mount the terrace steps.

The long train of her gold-embroidered gown swept the dead leaves off the steps, making a faint harmonious sh—sh—sh as she glided up, with one hand resting on the balustrade, the rosy light of dawn making an aureole of gold round her hair, and causing the rubies on her head and arms to sparkle. She reached the tall glass doors which led into the house. Before entering, she paused once again to look at him, hoping against hope to see his arms stretched out to her, and to hear his voice calling her back. But he had not moved; his massive figure looked the very personification of unbending pride, of fierce obstinacy.

Hot tears again surged to her eyes, as she would not let him see them, she turned quickly within, and ran as fast as she could up to her own rooms.

Had she but turned back then, and looked out once more on to the rose-lit garden, she would have seen that which would have made her own sufferings seem but light and easy to bear—a strong man, overwhelmed with his own passion and his own despair. Pride had given way at last, obstinacy was gone: the will was powerless. He was but a man madly, blindly, passionately in love, and as soon as her light footsteps had died away within the house, he knelt down upon the terrace steps, and in the very madness of his love he kissed one by one the places where her small foot had trodden, and the stone balustrade there, where her tiny hand had rested last.

❒