Chapter 1

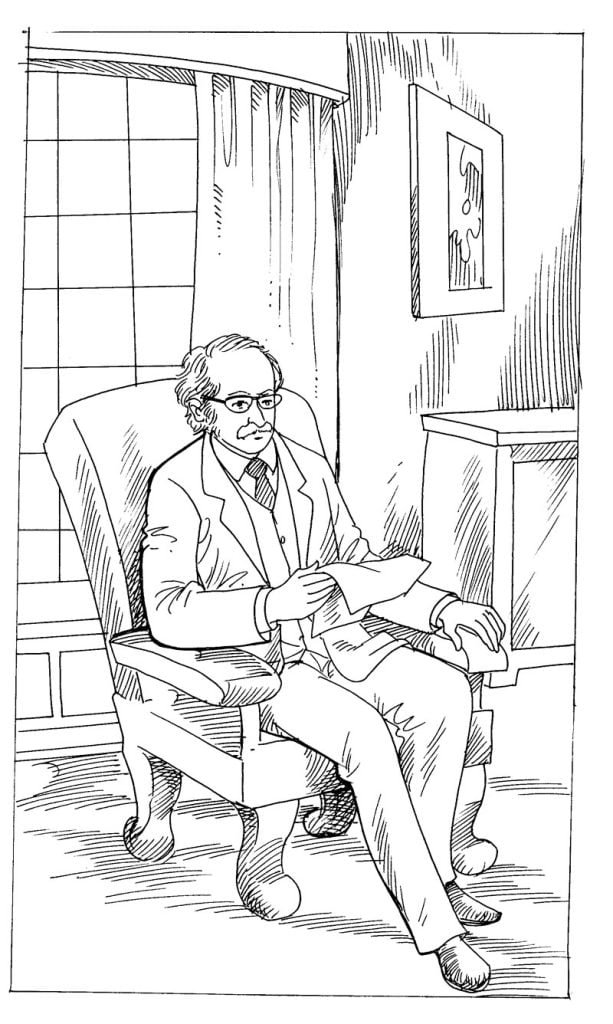

When you are getting on in years (but not ill, of course), you get very sleepy at times, and the hours seem to pass like lazy cattle moving across a landscape. It was like that for Chips as the autumn term progressed and the days shortened till it was actually dark enough to light the gas before call-over.

For Chips, like some old sea captain, still measured time by the signals of the past; and well he might, for he lived at Mrs. Wickett’s, just across the road from the School. He had been there more than a decade, ever since he finally gave up his mastership; and it was Brookfield far more than Greenwich time that both he and his landlady kept.

“Mrs. Wickett,” Chips would sing out, in that jerky, high-pitched voice that had still a good deal of sprightliness in it, “you might bring me a cup of tea before prep, will you?”

When you are getting on in years it is nice to sit by the fire and drink a cup of tea and listen to the school bell sounding dinner, call-over, prep, and lights-out. Chips always wound up the clock after that last bell; then he put the wire guard in front of the fire, turned out the gas, and carried a detective novel to bed. Rarely did he read more than a page of it before sleep came swiftly and peacefully, more like a mystic intensifying of perception than any changeful entrance into another world. For his days and nights were equally full of dreaming.

He was getting on in years (but not ill, of course); indeed, as Doctor Merivale said, “There was really nothing the matter with him, “My dear fellow, you’re fitter than I am,” Merivale would say, sipping a glass of sherry when he called every fortnight or so, “You’re past the age when people get these horrible diseases; you’re one of the few lucky ones who’re going to die a really natural death. That is, of course, if you die at all. You’re such a remarkable old boy that one never knows.” But when Chips had a cold or when east winds roared over the fenlands, Merivale would sometimes take Mrs. Wickett aside in the lobby and whisper, “Look after him, you know. His chest it puts a strain on his heart. Nothing really wrong with him—only anno domini, but that’s the most fatal complaint of all, in the end.”

Anno domini . . . by Jove, yes. Born in 1848, and taken to the Great Exhibition as a toddling child—not many people still alive could boast a thing like that. Besides, Chips could even remember Brookfield in Wetherby’s time. A phenomenon, that was.

Wetherby had been an old man in those days—1870—easy to remember because of the Franco-Prussian War. Chips had put in for Brookfield after a year at Melbury, which he hadn’t liked, because he had been ragged there a good deal. But Brookfield he had liked, almost from the beginning. He remembered that day of his preliminary interview—sunny June, with the air full of flower scents and the plick-plock of cricket on the pitch.

Brookfield was playing Barnhurst, and one of the Barnhurst boys, a chubby little fellow, made a brilliant century. Queer that a thing like that should stay in the memory so clearly. Wetherby himself was very fatherly and courteous; he must have been ill then, poor chap, for he died during the summer vacation, before Chips began his first term. But the two had seen and spoken to each other, anyway.

Chips often thought, as he sat by the fire at Mrs. Wickett’s: I am probably the only man in the world who has a vivid recollection of old Wetherby. Vivid, yes; it was a frequent picture in his mind, that summer day with the sunlight filtering through the dust in Wetherby’s study. “You are a young man, Mr. Chipping, and Brookfield is an old foundation. Youth and age often combine well. Give your enthusiasm to Brookfield, and Brookfield will give you something in return. And don’t let anyone play tricks with you. I gather that discipline was not always your strong point at Melbury.”

“Well, no, perhaps not, sir.”

“Never mind; you’re full young; it’s largely a matter of experience. You have another chance here. Take up a firm attitude from the beginning—that’s the secret of it.”

Perhaps it was. He remembered that first tremendous ordeal of taking prep; a September sunset more than half a century ago; Big Hall full of lusty barbarians ready to pounce on him as their legitimate prey. His youth, fresh-complexioned, high-collared, and side-whiskered (odd fashions people followed in those days), at the mercy of five hundred unprincipled ruffians to whom the baiting of new masters was a fine art, an exciting sport, and something of a tradition. Decent little beggars individually, but, as a mob, just pitiless and implacable.

The sudden hush as he took his place at the desk on the dais; the scowl he assumed to cover his inward nervousness; the tall clock ticking behind him, and the smells of ink and varnish; the last blood-red rays slanting in slabs through the stained-glass windows. Someone dropped a desk lid. Quickly, he must take everyone by surprise; he must show that there was no nonsense about him. “You there in the fifth row—you with the red hair—what’s your name?”

“Colley, sir.”

“Very well, Colley, you have a hundred lines.”

No trouble at all after that. He had won his first round.

And years later, when Colley was an alderman of the City of London and a baronet and various other things, he sent his son (also red-haired) to Brookfield, and Chips would say, “Colley, your father was the first boy I ever punished when I came here twenty-five years ago. He deserved it then, and you deserve it now.” How they all laughed; and how Sir Richard laughed when his son wrote home the story in next Sunday’s letter!

And again, years after that, many years after that, there was an even better joke. For another Colley had just arrived—son of the Colley who was a son of the first Colley. And Chips would say, punctuating his remarks with that little ‘umph-um’ that had by then become a habit with him, “Colley, you are—umph—a splendid example of—umph—inherited traditions. I remember your grandfather—umph—he could never grasp the Ablative Absolute. A stupid fellow, your grandfather. And your father, too—umph—I remember him—he used to sit at that far desk by the wall—he wasn’t much better, either. But I do believe—my dear Colley— that you are—umph—the biggest fool of the lot!” Roars of laughter.

A great joke, this growing old—but a sad joke, too, in a way. And as Chips sat by his fire with autumn gales rattling the windows, the waves of humor and sadness swept over him very often until tears fell, so that when Mrs. Wickett came in with his cup of tea she did not know whether he had been laughing or crying. And neither did Chips himself.