Chapter 2

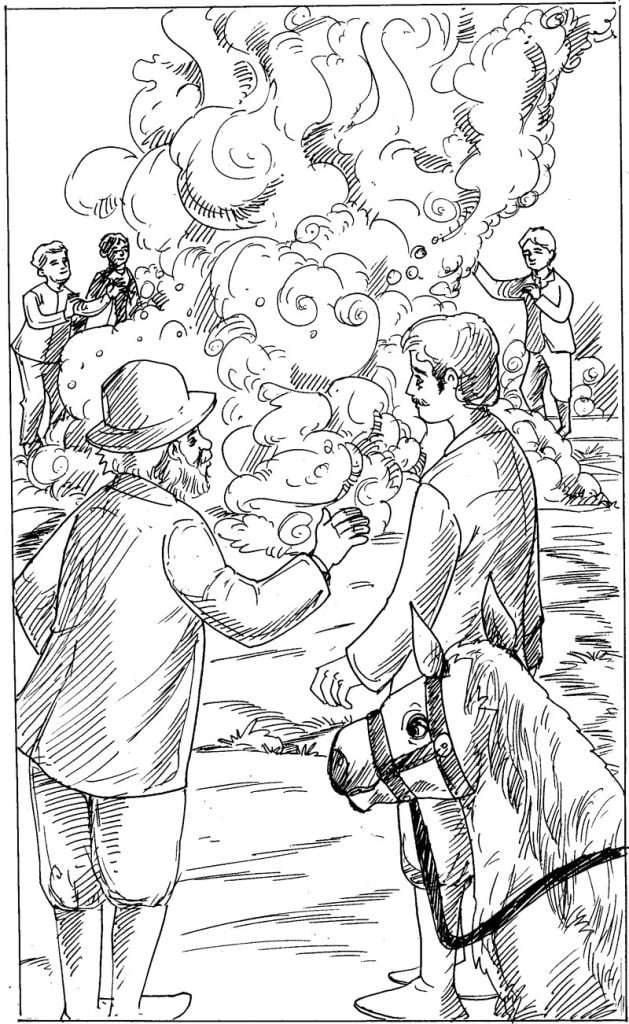

The next morning, as soon as Jacob had given the children their breakfast, he set off towards Arnwood. He knew that Benjamin had stated his intention to return with the horse and see what had taken place, and he knew him well enough to feel sure that he would do so. He thought it better to see him if possible, and ascertain the fate of Miss Judith. Jacob arrived at the still smoking ruins of the mansion, and found several people there, mostly residents within a few miles, some attracted by curiosity, others busy in collecting the heavy masses of lead which had been melted from the roof, and appropriating them to their own benefit; but much of it was still too hot to be touched, and they were throwing snow on it to cool it, for it had snowed during the night. At last, Jacob perceived Benjamin on horseback riding leisurely toward him, and immediately went up to him.

“Well, Benjamin, this is a woeful sight. What is the news from Lymington?”

“Lymington is full of troopers, and they are not over-civil,” replied Benjamin. “And the old lady—where is she?”

“Ah, that’s a sad business,” replied Benjamin, “and the poor children, too. Poor Master Edward! he would have made a brave gentleman.”

“But the old lady is safe,” rejoined Jacob. “Did you see her?”

“Yes, I saw her; they thought she was King Charles—poor old soul.”

“But they have found out their mistake by this time?”

“Yes, and James Southwold has found it out too,” replied Benjamin; “to think of the old lady breaking his neck!”

“Breaking his neck? You don’t say so! How was it?”

“Why, it seems that Southwold thought that she was King Charles dressed up as an old woman, so he seized her and strapped her fast behind him, and galloped away with her to Lymington; but she struggled and kicked so manfully, that he could not hold on, and off they went together, and he broke his neck.”

“Indeed! A judgment—a judgment upon a traitor,” said Jacob.

“They were picked up, strapped together as they were, by the other troopers, and carried to Lymington.”

“Well, and where is the old lady, then? Did you see and speak to her?”

“I saw her, Jacob, but I did not speak to her. I forgot to say that, when she broke Southwold’s neck, she broke her own too.”

“Then the old lady is dead?”

“Yes, that she is,” replied Benjamin; “but who cares about her? it’s the poor children that I pity. Martha has been crying ever since.”

“I don’t wonder.”

“I was at the Cavalier, and the troopers were there, and they were boasting of what they had done, and called it a righteous work. I could not stand that, and I asked one of them if it were a righteous work to burn poor children in their beds? So he turned round, and struck his sword upon the floor, and asked me whether I was one of them—’Who are you, then?’ and I—all my courage went away, and I answered, I was a poor rat-catcher. ‘A rat-catcher; are you? Well, then, Mr. Ratcatcher, when you are killing rats, if you find a nest of young ones, don’t you kill them too? or do you leave them to grow, and become mischievous, eh?’ ‘I kill the young ones, of course,’ replied I. ‘Well, so do we Malignants whenever we find them.’ I didn’t say a word more, so I went out of the house as fast as I could.”

“Have you heard any thing about the king?” inquired Jacob.

“No, nothing; but the troopers are all out again, and, I hear, are gone to the forest.”

“Well, Benjamin, good-bye, I shall be off from this part of the country—it’s no use my staying here. Where’s Agatha and cook?”

“They came to Lymington early this morning.”

“Wish them good-bye for me, Benjamin.”

“Where are you going, then?”

“I can’t exactly say, but I think London way. I only staid here to watch over the children; and now that they are gone, I shall leave Arnwood forever.”

Jacob, who was anxious, on account of the intelligence he had received of the troopers being in the forest, to return to the cottage, shook hands with Benjamin, and hastened away. “Well,” thought Jacob, as he wended his way, “I’m sorry for the poor old lady, but still, perhaps, it’s all for the best. Who knows what they might do with these children! Destroy the nest as well as the rats, indeed! they must find the nest first.” And the old forester continued his journey in deep thought.

We may here observe that, blood-thirsty as many of the Levelers were, we do not think that Jacob Armitage had grounds for the fears which he expressed and felt; that is to say, we believe that he might have made known the existence of the children to the Villiers family, and that they would never have been harmed by any body. That by the burning of the mansion they might have perished in the flames, had they been in bed, as they would have been at that hour, had he not obtained intelligence of what was about to be done, is true; but that there was any danger to them on account of their father having been such a stanch supporter of the king’s cause, is very unlikely, and not borne out by the history of the times: but the old forester thought otherwise; he had a hatred of the Puritans, and their deeds had been so exaggerated by rumor, that he fully believed that the lives of the children were not safe.

Under this conviction, and feeling himself bound by his promise to Colonel Beverley to protect them, Jacob resolved that they should live with him in the forest, and be brought up as his own grandchildren. He knew that there could be no better place for concealment; for, except the keepers, few people knew where his cottage was; and it was so out of the usual paths, and so imbosomed in lofty trees, that there was little chance of its being seen, or being known to exist. He resolved, therefore, that they should remain with him till better times; and then he would make known their existence to the other branches of the family, but not before. “I can hunt for them, and provide for them,” thought he, “and I have a little money, when it is required; and I will teach them to be useful; they must learn to provide for themselves.

There’s the garden, and the patch of land: in two or three years, the boys will be able to do something. I can’t teach them much; but I can teach them to fear God. We must get on how we can, and put our trust in Him who is a father to the fatherless.”

With such thoughts running in his head, Jacob arrived at the cottage, and found the children outside the door, watching for him. They all hastened to him, and the dog rushed before them, to welcome his master. “Down, Smoker, good dog! Well, Mr. Edward, I have been as quick as I could. How have Mr. Humphrey and your sisters behaved I But we must not remain outside to-day, for the troopers are scouring the forest, and may see you. Let us come in directly, for it would not do that they should come here.”

“Will they burn the cottage down?” inquired Alice, as she took Jacob’s hand.

“Yes, my dear, I think they would, if they found that you and your brothers were in it; but we must not let them see you.”

They all entered the cottage, which consisted of one large room in front, and two back rooms for bedrooms. There was also a third bedroom, which was behind the other two, but which had not any furniture in it.

“Now, let’s see what we can have for dinner—there’s venison left, I know,” said Jacob; “come, we must all be useful. Who will be cook?”

“I will be cook,” said Alice, “if you will show me how.”

“So you shall, my dear,” said Jacob, “and I will show you how. There’s some potatoes in the basket in the corner, and some onions hanging on the string; we must have some water—who will fetch it?”

“I will,” said Edward, who took a pail, and went out to the spring.

The potatoes were peeled and washed by the children—Jacob and Edward cut the venison into pieces—the iron pot was cleaned; and then the meat and potatoes put with water into the pot, and placed on the fire.

“Now I’ll cut up the onions, for they will make your eyes water.”

“I don’t care,” said Humphrey, “I’ll cut and cry at the same time.”

And Humphrey took up a knife, and cut away most manfully, although he was obliged to wipe his eyes with his sleeve very often.

“You are a fine fellow, Humphrey,” said Jacob. “Now we’ll put the onions in, and let it all boil up together. Now you see, you have cooked your own dinner; ain’t that pleasant?”

“Yes,” cried they all; “and we will eat our own dinners as soon as it is ready.”

“Then, Humphrey, you must get some of the platters down which are on the drawer; and, Alice, you will find some knives in the drawer. And let me see, what can little Edith do? Oh, she can go to the cupboard and find the salt-cellar. Edward, just look out, and if you see any body coming or passing, let me know. We must put you on guard till the troopers leave the forest.”

The children set about their tasks, and Humphrey cried out, as he very often did, “Now, this is jolly!”

While the dinner was cooking, Jacob amused the children by showing them how to put things in order; the floor was swept, the hearth was made tidy. He shewed Alice how to wash out a cloth, and Humphrey how to dust the chairs. They all worked merrily, while little Edith stood and clapped her hands.

But just before dinner was ready, Edward came in and said, “Here are troopers galloping in the forest!” Jacob went out, and observed that they were coming in a direction that would lead near to the cottage.

He walked in, and, after a moment’s thought, he said, “My dear children, those men may come and search the cottage; you must do as I tell you, and mind that you are very quiet. Humphrey, you and your sisters must go to bed, and pretend to be very ill. Edward, take off your coat and put on this old hunting-frock of mine. You must be in the bedroom attending your sick brother and sisters. Come, Edith, dear, you must play at going to bed, and have your dinner afterward.”

Jacob took the children into the bedroom, and, removing the upper dress, which would have betrayed that they were not the children of poor people, put them in bed, and covered them up to the chins with the clothes. Edward had put on the old hunting-shirt, which came below his knees, and stood with a mug of water in his hand by the bedside of the two girls. Jacob went to the outer room, to remove the platters laid out for dinner; and he had hardly done so when he heard the noise of the troopers, and soon afterward a knock at the cottage-door.

“Come in,” said Jacob.

“Who are you, my friend?” said the leader of the troop, entering the door.

“A poor forester, sir,” replied Jacob, “under great trouble.”

“What trouble, my man?”

“I have the children all in bed with the small-pox.”

“Nevertheless, we must search your cottage.”

“You are welcome,” replied Jacob, “only don’t frighten the children, if you can help it.”

The man, who was now joined by others, commenced his search. Jacob opened all the doors of the rooms, and they passed through. Little Edith shrieked when she saw them; but Edward patted her, and told her not to be frightened. The troopers, however, took no notice of the children; they searched thoroughly, and then came back to the front room.

“It’s no use remaining here,” said one of the troopers. “Shall we be off! I’m tired and hungry with the ride.”

“So am I, and there’s something that smells well.” said another.” What’s this, my good man?” continued he, taking off the lid of the pot.

“My dinner for a week,” replied Jacob. “I have no one to cook for me now, and can’t light a fire every day.”

“Well, you appear to live well, if you have such a mess as that every day in the week. I should like to try a spoonful or two.”

“And welcome, sir,” replied Jacob; “I will cook some more for myself.”

The troopers took him at his word; they sat down to the table, and very soon the whole contents of the kettle had disappeared. Having satisfied themselves, they got up, told him that his rations were so good that they hoped to call again; and, laughing heartily, they mounted their horses, and rode away.

“Well,” said Jacob, “they are very welcome to the dinner; I little thought to get off so cheap.” As soon as they were out of sight, Jacob called to Edward and the children to get up again, which they soon did. Alice put on Edith’s frock, Humphrey put on his jacket, and Edward pulled off the hunting-shirt.

“They’re gone now,” said Jacob, coming in from the door.

“And our dinners are gone,” said Humphrey, looking at the empty pot and dirty platters.

“Yes; but we can cook another, and that will be more play you know,” said Jacob. “Edward, go for the water; Humphrey, cut the onions; Alice, wash the potatoes; and Edith, help every body, while I cut up some more meat.”

“I hope it will be as good,” observed Humphrey; “that other did smell so nice!”

“Quite as good, if not better; for we shall improve by practice, and we shall have a better appetite to eat it with,” said Jacob.

“Nasty men eat our dinner,” said Edith. “Shan’t have any more. Eat this ourselves.”

And so they did as soon as it was cooked; but they were very hungry before they sat down.

“This is jolly!” said Humphrey with his mouth full.

“Yes, Master Humphrey. I doubt if King Charles eats so good a dinner this day. Mr. Edward, you are very grave and silent.”

“Yes, I am, Jacob. Have I not cause? Oh, if I could but have mauled those troopers!”

“But you could not; so you must make the best of it. They say that every dog has his day, and who knows but King Charles may be on the throne again!”

There were no more visits to the cottage that day, and they all went to bed, and slept soundly.

The next morning, Jacob, who was most anxious to learn the news, saddled the pony, having first given his injunctions to Edward how to behave in case any troopers should come to the cottage. He told him to pretend that the children were in bed with the small-pox, as they had done the day before. Jacob then traveled to Gossip Allwood’s, and he there learnt that King Charles had been taken prisoner, and was at the Isle of Wight, and that the troopers were all going back to London as fast as they came.

Feeling that there was now no more danger to be apprehended from them, Jacob set off as fast as he could for Lymington. He went to one shop and purchased two peasant dresses which he thought would fit the two boys, and at another he bought similar apparel for the two girls. Then, with several other ready-made articles, and some other things which were required for the household, he made a large package, which he put upon the pony, and, taking the bridle, set off home, and arrived in time to superintend the cooking of the dinner, which was this day venison-steaks fried in a pan, and boiled potatoes.

When dinner was over, he opened his bundle, and told the little ones that, now they were to live in a cottage, they ought to wear cottage clothes, and that he had bought them some to put on, which they might rove about the woods in, and not mind tearing them. Alice and Edith went into the bedroom, and Alice dressed Edith and herself, and came out quite pleased with their change of dress. Humphrey and Edward put theirs on in the sitting-room, and they all fitted pretty well, and certainly were very becoming to the children.

“Now, recollect, you are all my grandchildren,” said Jacob; “for I shall no longer call you Miss and Master—that we never do in a cottage. You understand me, Edward, of course?” added Jacob.

Edward nodded his head; and Jacob telling the children that they might now go out of the cottage and play, they all set off, quite delighted with clothes which procured them their liberty.

We must now describe the cottage of Jacob Armitage, in which the children have in future to dwell. As we said before, it contained a large sitting-room, or kitchen, in which was a spacious hearth and chimney, table, stools, cupboards, and dressers: the two bedrooms which adjoined it were now appropriated, one for Jacob and the other for the two boys; the third, or inner bedroom, was arranged for the two girls, as being more retired and secure. But there were outhouses belonging to it: a stall, in which White Billy, the pony, lived during the winter; a shed and pigsty rudely constructed, with an inclosed yard attached to them; and it had, moreover, a piece of ground of more than an acre, well fenced in to keep out the deer and game, the largest portion of which was cultivated as a garden and potato-ground, and the other, which remained in grass, contained some fine old apple and pear-trees.

Such was the domicile; the pony, a few fowls, a sow and two young pigs, and the dog Smoker, were the animals on the establishment. Here Jacob Armitage had been born—for the cottage had been built by his grandfather—but he had not always remained at the cottage. When young, he felt an inclination to see more of the world, and had for several years served in the army. His father and brother had lived in the establishment at Arnwood, and he was constantly there as a boy The chaplain of Arnwood had taken a fancy to him, and taught him to read—writing he had not acquired. As soon as he grew up, he served, as we have said, in the troop commanded by Colonel Beverley’s father; and, after his death, Colonel Beverley had procured him the situation of forest ranger, which had been held by his father, who was then alive, but too aged to do duty. Jacob Armitage married a good and devout young woman, with whom he lived several years, when she died, without bringing him any family; after which, his father being also dead, Jacob Armitage had lived alone until the period at which we have commenced this history.

The old forester lay awake the whole of this night, reflecting how he should act relative to the children; he felt the great responsibility that he had incurred, and was alarmed when he considered what might be the consequences if his days were shortened. What would become of them—living in so sequestered a spot that few knew even of its existence—totally shut out from the world, and left to their own resources? He had no fear, if his life was spared, that they would do well; but if he should be called away before they had grown up and were able to help themselves, they might perish. Edward was not fourteen years old; it was true that he was an active, brave boy, and thoughtful for his years; but he had not yet strength or skill sufficient for what would be required.

Humphrey, the second, also promised well; but still they were all children. “I must bring them up to be useful—to depend upon themselves; there is not a moment to be lost, and not a moment shall be lost; I will do my best, and trust to God; I ask but two or three years, and by that time I trust that they will be able to do without me. They must commence to-morrow the life of foresters’ children.”

Acting upon this resolution, Jacob, as soon as the children were dressed, and in the sitting-room, opened his Bible, which he had put on the table, and said:

“My dear children, you know that you must remain in this cottage, that the wicked troopers may not find you out; they killed your father, and if I had not taken you away, they would have burned you in your beds. You must, therefore, live here as my children, and you must call yourselves by the name of Armitage, and not that of Beverley; and you must dress like children of the forest, as you do now, and you must do as children of the forest do—that is, you must do every thing for yourselves, for you can have no servants to wait upon you. We must all work—but you will like to work if you all work together, for then the work will be nothing but play. Now, Edward is the oldest, and he must go out with me in the forest, and I must teach him to kill deer and other game for our support; and when he knows how, then Humphrey shall come out and learn how to shoot.”

“Yes,” said Humphrey, “I’ll soon learn.”

“But not yet, Humphrey, for you must do some work in the mean time; you must look after the pony and the pigs, and you must learn to dig in the garden with Edward and me when we do not go out to hunt; and sometimes I shall go by myself, and leave Edward to work with you when there is work to be done. Alice, dear, you must, with Humphrey, light the fire and clean the house in the morning. Humphrey will go to the spring for water, and do all the hard work; and you must learn to wash, my dear Alice—I will show you how; and you must learn to get dinner ready with Humphrey, who will assist you; and to make the beds. And little Edith shall take care of the fowls, and feed them every morning, and look for the eggs—will you, Edith?”

“Yes,” replied Edith, “and feed all the little chickens when they are hatched, as I did at Arnwood.”

“Yes, dear, and you’ll be very useful. Now you know that you can not do all this at once. You will have to try and try again; but very soon you will, and then it will be all play. I must teach you all, and every day you will do it better, till you want no teaching at all. And now, my dear children, as there is no chaplain here, we must read the Bible every morning. Edward can read, I know; can you, Humphrey?”

“Yes, all except the big words.”

“Well, you will learn them by-and-by. And Edward and I will teach Alice and Edith to read in the evenings, when we have nothing to do. It will be an amusement. Now tell me, do you all like what I have told you?”

“Yes,” they all replied; and then Jacob Armitage read a chapter in the Bible, after which they all knelt down and said the Lord’s prayer. As this was done every morning and every evening, I need not repeat it again. Jacob then showed them again how to clean the house, and Humphrey and Alice soon finished their work under his directions; and then they all sat down to breakfast, which was a very plain one, being generally cold meat, and cakes baked on the embers, at which Alice was soon very expert; and little Edith was very useful in watching them for her, while she busied herself about her other work. But the venison was nearly all gone; and after breakfast Jacob and Edward, with the dog Smoker, went out into the woods. Edward had no gun, as he only went out to be taught how to approach the game, which required great caution; indeed Jacob had no second gun to give him, if he had wished so to do.

“Now, Edward, we are going after a fine stag, if we can find him, which I doubt not; but the difficulty is, to get within shot of him. Recollect that you must always be hid, for his sight is very quick; never be heard, for his ear is sharp; and never come down to him with the wind, for his scent is very fine. Then you must hunt according to the hour of the day. At this time he is feeding; two hours hence he will be lying down in the high fern. The dog is no use unless the stag is badly wounded, when the dog will take him. Smoker knows his duty well, and will hide himself as close as we do. We are now going into the thick wood ahead of us, as there are many little spots of cleared ground in it where we may find the deer; but we must keep more to the left, for the wind is to the eastward, and we must walk up against it. And now that we are coming into the wood, recollect, not a word must be said, and you must walk as quietly as possible, keeping behind me. Smoker, to heel!” They proceeded through the wood for more than a mile, when Jacob made a sign to Edward, and dropped down into the fern, crawling along to an open spot, where, at some distance, were a stag and three deer grazing. The deer grazed quietly, but the stag was ever and anon raising up his head and snuffing the air as he looked round, evidently acting as a sentinel for the females.

The stag was perhaps a long quarter of a mile from where they had crouched down in the fern. Jacob remained immovable till the animal began to feed again, and then he advanced, crawling through the fern, followed by Edward and the dog, who dragged himself on his stomach after Edward. This tedious approach was continued for some time, and they had neared the stag to within half the original distance, when the animal again lifted up his head and appeared uneasy. Jacob stopped and remained without motion. After a time the stag walked away, followed by the does, to the opposite side of the clear spot on which they had been feeding, and, to Edward’s annoyance, the animal was half a mile from them. Jacob turned round and crawled into the wood, and when he knew that they were concealed, he rose on his feet and said,

“You see, Edward, that it requires patience to stalk a deer. What a princely fellow! but he has probably been alarmed this morning, and is very uneasy. Now we must go through the woods till we come to the lee of him on the other side of the dell. You see he has led the does close to the thicket, and we shall have a better chance when we get there, if we are only quiet and cautious.”

“What startled him, do you think?” said Edward.

“I think, when you were crawling through the fern after me, you broke a piece of rotten stick that was under you. Did you not?”

“Yes, but that made but little noise.”

“Quite enough to startle a red deer, Edward, as you will find out before you have been long a forester. These checks will happen, and have happened to me a hundred times, and then all the work is to be done over again. Now then to make the circuit—we had better not say a word. If we get safe now to the other side, we are sure of him.”

They proceeded at a quick walk through the forest, and in half an hour had gained the side where the deer were feeding. When about three hundred yards from the game, Jacob again sunk down on his hands and knees, crawling from bush to bush, stopping whenever the stag raised his head, and advancing again when it resumed feeding; at last they came to the fern at the side of the wood, and crawled through it as before, but still more cautiously as they approached the stag. In this manner they arrived at last to within eighty yards of the animal, and then Jacob advanced his gun ready to put it to his shoulder, and, as he cocked the lock, raised himself to fire.

The click occasioned by the cocking of the lock roused up the stag instantly, and he turned his head in the direction from whence the noise proceeded; as he did so Jacob fired, aiming behind the animal’s shoulder: the stag made a bound, came down again, dropped on his knees, attempted to run, and fell dead, while the does fled away with the rapidity of the wind.

Edward started up on his legs with a shout of exultation. Jacob commenced reloading his gun, and stopped Edward as he was about to run up to where the animal lay.

“Edward, you must learn your craft,” said Jacob; “never do that again; never shout in that way—on the contrary, you should have remained still in the fern.”

“Why so?—the stag is dead.”

“Yes, my dear boy, that stag is dead; but how do you know but what there may be another lying down in the fern close to us, or at some distance from us, which you have alarmed by your shout? Suppose that we both had guns, and that the report of mine had started another stag lying in the fern within shot, you would have been able to shoot it; or if a stag was lying at a distance, the report of the gun might have started him so as to induce him to move his head without rising. I should have seen his antlers move and have marked his lair, and we should then have gone after him and stalked him too.”

“I see,” replied Edward, “I was wrong; but I shall know better another time.”

“That’s why I tell you, my boy,” replied Jacob. “Now let us go to our quarry. Ay, Edward, this is a noble beast. I thought that he was a hart royal, and so he is.”

“What is a hart royal, Jacob?”

“Why, a stag is called a brocket until he is three years old, at four years he is a staggart; at five years a warrantable stag; and after five years he becomes a hart royal.”

“And how do you know his age?”

“By his antlers: you see that this stag has nine antlers; now, a brocket has but two antlers, a staggart three, and a warrantable stag but four; at six years old, the antlers increase in number until they sometimes have twenty or thirty. This is a fine beast, and the venison is now getting very good. Now you must see me do the work of my craft.”

Jacob then cut the throat of the animal, and afterward cut off its head and took out its bowels.

“Are you tired, Edward?” said Jacob, as he wiped his hunting-knife on the coat of the stag.

“No, not the least.”

“Well, then, we are now, I should think, about four or five miles from the cottage. Could you find your way home? but that is of no consequence—Smoker will lead you home by the shortest path. I will stay here, and you can saddle White Billy and come back with him, for he must carry the venison back. It’s more than we can manage—indeed, as much as we can manage with White Billy to help us. There’s more than twenty stone of venison lying there, I can tell you.”

Edward immediately assented, and Jacob, desiring Smoker to go home, set about flaying and cutting up the animal for its more convenient transportation. In an hour and a half, Edward, attended by Smoker, returned with the pony, on whose back the chief portion of the venison was packed.

Jacob took a large piece on his own shoulders, and Edward carried another, and Smoker, after regaling himself with a portion of the inside of the animal, came after them. During the walk home, Jacob initiated Edward into the terms of venery and many other points connected with deer-stalking, with which we shall not trouble our readers. As soon as they arrived at the cottage, the venison was hung up, the pony put in the stable, and then they sat down to dinner with an excellent appetite after their long morning’s walk. Alice and Humphrey had cooked the dinner themselves, and it was in the pot, smoking hot, when they returned; and Jacob declared he never ate a better mess in his life. Alice was not a little proud of this, and of the praises she received from Edward and the old forester. The next day, Jacob stated his intention of going to Lymington to dispose of a large portion of the venison, and bring back a sack of oatmeal for their cakes. Edward asked to accompany him, but Jacob replied,

“Edward, you must not think of showing yourself at Lymington, or any where else, for a long while, until you are grown out of memory. It would be folly, and you would risk your sisters’ and brother’s lives, perhaps, as well as your own. Never mention it again: the time will come when it will be necessary, perhaps; if so, it can not be helped. At present you would be known immediately. No, Edward, I tell you what I mean to do: I have a little money left, and I intend to buy you a gun, that you may learn to stalk deer yourself without me; for, recollect, if any accident should happen to me, who is there but you to provide for your brother and sisters? At Lymington I am known to many; but out of all who know me, there is not one who knows where my cottage is; they know that I live in the New Forest, and that I supply them venison, and purchase other articles in return. That is all that they know: and I may therefore go without fear. I shall sell the venison to-morrow, and bring you back a good gun; and Humphrey shall have the carpenters’ tools which he wishes for, for I think, by what he does with his knife, that he has a turn that way, and it may be useful. I must also get some other tools for Humphrey and you, as we shall then be able to work all together; and some threads and needles for Alice, for she can sew a little, and practice will make her more perfect.”

Jacob went off to Lymington as he had proposed, and returned late at night with White Billy well loaded; he had a sack of oatmeal, some spades and hoes, a saw and chisels, and other tools; two scythes and two three-pronged forks; and when Edward came to meet him, he put into his hand a gun with a very long barrel.

“I believe, Edward, that you will find that a good one, for I know where it came from. It belonged to one of the rangers, who was reckoned the best shot in the Forest. I know the gun, for I have seen it on his arm, and have taken it in my hand to examine it more than once. He was killed at Naseby, with your father, poor fellow! and his widow sold the gun to meet her wants.”

“Well,” replied Edward, “I thank you much, Jacob, and I will try if I can not kill as much venison as will pay you back the purchase-money—I will, I assure you.”

“I shall be glad if you do, Edward; not because I want the money back, but because then I shall be more easy in my mind about you all, if any thing happens to me. As soon as you are perfect in your woodcraft, I shall take Humphrey in hand, for there is nothing like having two strings to your bow. To-morrow we will not go out: we have meat enough for three weeks or more; and now the frost has set in, it will keep well. You shall practice at a mark with your gun, that you may be accustomed to it; for all guns, even the best, require a little humoring.”

Edward, who had often fired a gun before, proved the next morning that he had a very good eye; and, after two or three hours’ practice, hit the mark at a hundred yards almost every time.

“I wish you would let me go out by myself,” said Edward, overjoyed at his success.

“You would bring home nothing, boy,” replied Jacob. “No, no, you have a great deal to learn yet; but I tell you what you shall do: any time that we are not in great want of venison, you shall have the first fire.”

“Well, that will do,” replied Edward.

The winter now set in with great severity, and they remained almost altogether within doors. Jacob and the boys went out to get firewood, and dragged it home through the snow.

“I wish, Jacob,” said Humphrey, “that I was able to build a cart, for it would be very useful, and White Billy would then have something to do; but I can’t make the wheels, and there is no harness.”

“That’s not a bad idea of yours, Humphrey,” replied Jacob; “we will think about it. If you can’t build a cart, perhaps I can buy one. It would be useful if it were only to take the dung out of the yard on the potato-ground, for I have hitherto carried it out in baskets, and it’s hard work.”

“Yes, and we might saw the wood into billets, and carry it home in the cart, instead of dragging it in this way; my shoulder is quite sore with the rope, it cuts me so.”

“Well, when the weather breaks up, I will see what I can do, Humphrey; but just now the roads are so blocked up, that I do not think we could get a cart from Lymington to the cottage, although we can a horse, perhaps.”

But if they remained in-doors during the inclement weather, they were not idle. Jacob took this opportunity to instruct the children in every thing. Alice learned how to wash and how to cook. It is true, that sometimes she scalded herself a little, sometimes burned her fingers; and other accidents did occur, from the articles employed being too heavy for them to lift by themselves; but practice and dexterity compensated for want of strength, and fewer accidents happened every day.

Humphrey had his carpenters’ tools; and although at first he had many failures, and wasted nails and wood, by degrees he learned to use his tools with more dexterity, and made several little useful articles. Little Edith could now do something, for she made and baked all the oatmeal cakes, which saved Alice a good deal of time and trouble in watching them.

It was astonishing how much the children could do, now that there was no one to do it for them; and they had daily instruction from Jacob. In the evening Alice sat down with her needle and thread to mend the clothes; at first they were not very well done, but she improved every day. Edith and Humphrey learnt to read while Alice worked, and then Alice learnt; and thus passed the winter away so rapidly, that, although they had been five months at the cottage, it did not appear as if they had been there as many weeks. All were happy and contented, with the exception, perhaps, of Edward, who had fits of gloominess, and occasionally showed signs of impatience as to what was passing in the world, of which he remained in ignorance.

That Edward Beverley had fits of gloominess and impatience is not surprising. Edward had been brought up as the heir of Arnwood; and a boy at a very early age imbibes notions of his position, if it promises to be a high one. He was not two miles from that property which by right was his own. His own mansion had been reduced to ashes—he himself was hidden in the forest; and he could but not feel his position.

He sighed for the time when the king’s cause should be again triumphant, and his arrival at that age when he could in person support and uphold the cause. He longed to be in command, as his father had been—to lead his men on to victory—to recover his property, and to revenge himself on those who had acted so cruelly toward him.

This was human nature; and much as Jacob Armitage would expostulate with him, and try to divert his feelings into other channels—long as he would preach to him about forgiveness of injuries, and patience until better times should come, Edward could not help brooding over these thoughts, and if ever there was a breast animated with intense hatred against the Puritans, it was that of Edward Beverley. Although this was to be lamented, it could not create surprise or wonder in the old forester. All he could do was, as much as possible to reason with him, to soothe his irritated feelings, and by constant employment try to make him forget for a time the feelings of ill-will which he had conceived.

One thing was, however, sufficiently plain to Edward, which was, that whatever might be his wrongs, he had not the power at present to redress them; and this feeling, perhaps, more than any other, held him in some sort of check; and as the time when he might have an opportunity appeared far distant, even to his own sanguine imagination, so by degrees did he contrive to dismiss from his thoughts what it was no use to think about at present.

❒