Chapter-14

It was summer in England. Adele, weary with gathering wild strawberries in Hay Lane half the day, had gone to bed with the sun. Jane watched her drop asleep. When she left her, she sought the garden. It was the sweetest hour of the twenty-four : day its fervid fires had wasted. Dew fell cool on panting plain and scorched summit. Where the sun had gone down in simple state—pure of the pomp of clouds—spread a solemn purple, burning with the light of red jewel and furnace flame at one point, on one hill-peak, and extending high and wide, soft and still softer, over half heaven. The east had its own charm of fine deep blue, and its own modest gem, a rising and solitary star: soon it would boast the moon; but she was yet beneath the horizon.

Jane walked a while on the pavement; but a subtle, well-known scent—that of a cigar—stole from some window. Jane saw the library casement open a hand-breadth; she knew she might be watched thence. So, Jane went apart into the orchard. No nook in the grounds more sheltered and more Eden-like; it was full of trees. It bloomed with flowers : a very high wall shut it out from the court, on one side; on the other, a beech avenue screened it from the lawn. At the bottom was a sunk fence; its sole separation from lonely fields : a winding walk, bordered with laurels and terminating in a giant horse-chestnut, circled at the base by a seat, led down to the fence. Here one could wander unseen.

While such honey-dew fell, such silence reigned, such gloaming gathered, Jane felt as if she could haunt such shade for ever; but in threading the flower and fruit parterres at the upper part of the enclosure, enticed there by the light the now rising moon cast on this more open quarter, her step was stayed—not by sound, not by sight, but once more by a warning fragrance.

Sweet-briar and southernwood, jasmine, pink and rose had long been yielding their evening sacrifice of incense. This new scent was neither of shrub nor of flower. It was—she knew it well—Mr Rochester’s cigar. She looked around and listened. She saw trees laden with ripening fruit. She heard a nightingale warbling in a wood half a mile off; no moving form was visible, no coming step audible; but that perfume increased. Jane must flee. She made for the wicket leading to the shrubbery. She saw Mr Rochester entering. She stepped aside into the ivy recess. He would not stay long; he would soon return whence he came. If Jane sat still, he would never see her.

But no—eventide was as pleasant to him as to her, and that antique garden as attractive. Mr Rochester strolled on, now lifting the gooseberry tree branches to look at the fruit large as plums, with which they were laden. He took a ripe cherry from the wall and stooped towards a knot of flowers, either to inhale their fragrance or to admire the dew-beads on their petals. A great moth went humming by Jane. It alighted on a plant at Mr Rochester’s foot. He saw it and bent to examine it.

‘Now, he has his back towards me,’ Jane thought, ‘He is occupied perhaps. If I walk softly, I can slip away unnoticed.’

Jane trade on an edging of turf that the crackle of the pebbly gravel might not betray her. He was standing among the beds at a yard or two distant from where Jane had to pass. The moth apparently engaged him.

‘I shall get by very well,’ Jane meditated. As she crossed his shadow, thrown long over the garden by the moon, not yet risen high, he said quietly, without turning—”Jane! come and look at this fellow.”

Jane had made no noise. She had not eyes behind. Could his shadow feel? She stared at first. Then, she approached him.

“Look at its wings,” said Mr Rochester, “It reminds me rather of a West Indian insect. One does not often see so large and gay a night-rover in England. It has flown there.”

The moth roamed away. Jane was sheepishly retreating also, but Mr Rochester followed her. When they reached the wicket, he said, “Turn back; on so lovely a night it is a shame to sit in the house; surely nobody can wish to go to bed while sunset is thus at meeting with moonrise.”

It was one of Jane’s faults that though her tongue was sometimes prompt enough of an answer yet there were times when it sadly failed her in framing an excuse. Always the lapse occurred at some crisis when a facile word or plausible pretext was specially wanted to get her out of painful embarrassment. She did not like to walk at this hour alone with Mr Rochester in the shadowy orchard; but she could not find a reason to allege for leaving him. She followed with lagging step, and thoughts busily bent on discovering a means of extrication; but he himself looked so composed and grave as well. Jane became ashamed of feeling any confusion. The evil—if evil existent or prospective there was—seemed to lie with her only, his mind was unconscious and quiet.

“Jane,” he recommenced, as they entered the laurel walk, and slowly strayed down in the direction of the sunk fence and the horse-chestnut.

“Have you liked Thornfield? Isn’t it a beautiful place in summer?”

Jane replied, “Yes, it is a nice place. I have now got attached to it.”

Then, Mr Rochester said, “Jane! I am going to marry Miss Ingram. Adele will be admitted to school. You will be free. You must look out for another situation.”

Hearing the words, Jane felt sad. She loved Adele a lot. She said to Mr Rochester, “Sir! may I continue here as an ordinary member of Thornfield Hall?”

“I grieve to leave Thornfield. I love Thornfield because I have lived in it a full and delightful life—momentarily at least. I have not been trampled on. I have not been petrified. I have not been buried with inferior minds, and excluded from every glimpse of communion with what is bright, energetic and high. I have talked face to face with what I delight in. I have known you, Mr Rochester. It strikes me with terror and anguish to feel. I absolutely must be torn from you for ever. I see the necessity of departure. It is like looking on the necessity of death.”

Mr Rochester replied, “Jane! after a month or so, I shall get married. You need not worry at all. I have found a situation for you in Ireland. You will certainly like that place.”

But Jane was not at all interested in getting an employment in Ireland as it was a long way from Thornfield. While talking to each other, both Mr Rochester and Jane sat under a chestnut tree. A cool breeze was blowing at that time. Nightingales were singing in the woods. In all, it was a good atmosphere.

But Jane was sad at heart. The very thought of separation from Mr Rochester sent a wave of shiver down her spine. As a result, she started sobbing. After some moments, she said to Mr Rochester, “Sir! I will be left alone after you have married Miss Ingram. I can’t part from you.”

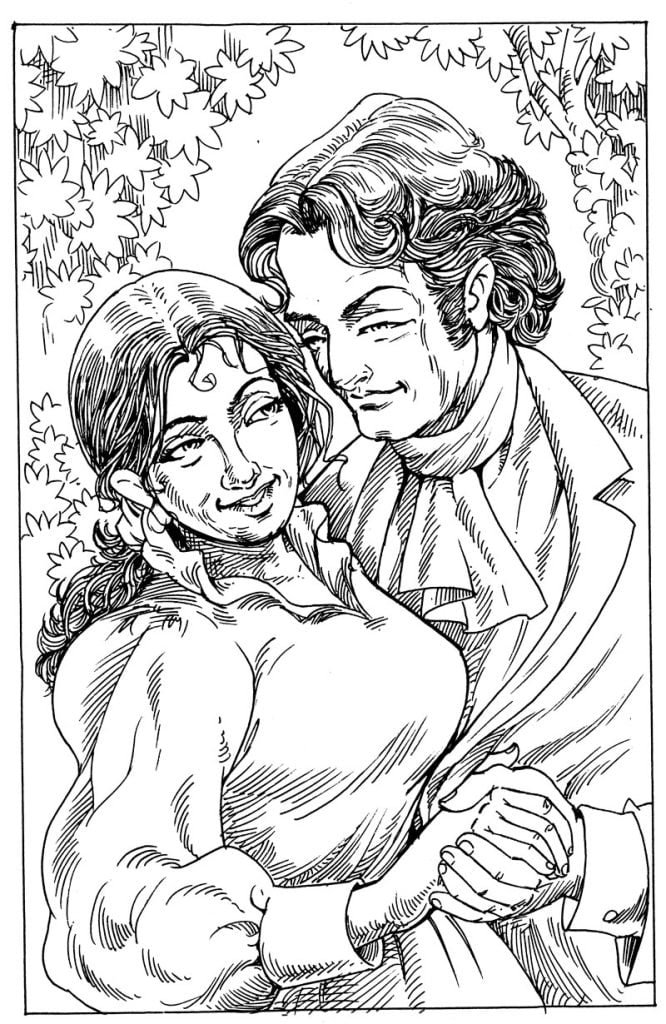

Mr Rochester retorted, “Who is going to marry Miss Ingram?” Saying these words he burst into a peal of laughter and held Jane in his arms. He placed a gentle kiss on one of the cheeks of Jane. Then, he resumed, “Jane! I love you more than anybody else. I have no respect for Miss Ingram for whom money is more important. Now, the opportune time has come for you to take me as your husband. I offer you my heart, my hand and a share of my all possessions. Please accept my love.”

Jane could not believe her ears. She said to Mr Rochester, “Sir! do you mean it? Do you sincerely wish me to be your life-partner?” Mr Rochester said in a humble tone, “I do.” Hearing the reply of Mr Rochester, Jane embraced Mr Rochester to her bosom. Finally, they were in love with each other. On one hand, Mr Rochester had found a beautiful life-partner in the person of Jane Eyre. On the other hand, Jane Eyre had found a doting husband in the person of Mr Rochester.

The couple sat there under the tree till late at night. When the clouds thundered and it began to rain, he hurried Jane up the walk, through the grounds, and into the house; but they were quite wet before they could pass the threshold. He was taking off Jane’s shawl in the hall and shaking the water out of her loosened hair. At that time, Mrs Fairfax emerged from her room. Jane did not observe her at first, nor did Mr Rochester. The lamp was lit. The clock was on the stroke of twelve.

“Hasten to take off your wet things,” said he, “and before you go, good night, good night, my darling!”

Mr Rochester kissed Jane repeatedly. When Jane looked up, on leaving his arms, there stood the widow, pale, grave and amazed. Jane only smiled at her and ran upstairs.

‘Explanation will do for another time,’ Jane thought. When she reached her chamber, she felt a pang at the idea she should even temporarily misconstrue what she had seen. By joy soon effaced every other feeling, and loud as the wind blew, near and deep as the thunder crashed, fierce and frequent as the lightning gleamed, cataract-like as the rain fell during a storm of two hours’ duration.

Jane experienced no fear and little awe. Mr Rochester came thrice to her door in the course of it to ask if she was safe and tranquil. That was comfort and that was strength for anything.