Chapter-6

Pestilence disease had claimed the lives of many girls at Lowood school.

When pestilence disease (the typhus fever) had fulfilled its mission of devastation at Lowood, it gradually disappeared from there; but not till its virulence and the number of its victims had drawn public attention on the school. Inquiry was made into the origin of the scourge, and by degrees various facts came out which excited public indignation in a high degree. The unhealthy nature of the site, the quantity and quality of the children’s food, the brackish fetid water used in preperation, in pupils’ wretched clothing and accomodation—all these things were discovered. The discovery produced a result mortifying to Mr Brocklehurst, but beneficial to the institution.

Several wealthy and benevolent individuals in the country subscribed largely for the erection of a more convenient building in a better situation; new regulations were made; improvements in diet and clothing were introduced; the funds of the school were entrusted to the management of a committee. Mr Brocklehurst, who from his wealth and family connections, could not be overlooked, still retained the post of treasurer. But he was aided in the discharge of his duties by gentlemen of rather more enlarged and sympathising minds; his office of inspector, too, was shared by those who knew how to combine reason with strictness, comfort with economy, compassion with uprightness. The school, thus improved, became in time a truly useful and noble institution.

Jane Eyre had been at Lowood school for eight long years—six as a pupil and two as a teacher. During these eight years, her life was uniform but not unhappy because she remained quite active. Miss Temple, the Superintendent of school, married a clergyman and went to a distant country.

Miss Temple, through all changes, had thus far continued superintendent of the seminary : to her instruction Jane owed the best part of her acquirements; her friendship and society had been Jane’s continued solace. She had stood her in the stead of mother, governess, and latterly, companion. From the day she left, Jane Eyre was no longer the same. With her was gone every settled feeling, every association that had made Lowood in some degree a home to Jane Eyre. She had imbibed from her something of her nature and much of her habits and more harmonious thoughts. What seemed better regulated feelings had become the inmates of Jane’s mind. She had given in allegiance to duty and order. She appeared a disciplined and subdued character.

But destiny in the shape of the Revd Mr Nasmyth, who married Miss Temple, came between Jane and Miss Temple. Jane saw her in her travelling dress step into a postchaise, shortly after the marriage ceremony. She watched the chaise mount the hill and disappear beyond its brow. Then, she retired to her own room. There, she spent in solitude the greater part of the half holiday granted in honour of the occasion.

Jane walked about the chamber most of the time. She imagined herself only to be regretting her loss, and thinking how to repair it. But when her reflections were concluded, she looked up and found that the afternoon was gone, and evening far advanced, another discovery dawned on her, namely that in the interval she had undergone a transforming process; that her mind had put off all it had borrowed of Miss Temple—or rather that she had taken with her the serene atmosphere.

Jane had been breathing in her vicinity. She was left in her natural element, and was beginning to feel the stirring of old emotions. It did not seem as if a prop were withdrawn, but rather as if a motive were gone. It was not the power to be tranquil which had failed her, but the reason for tranquillity was no more. Her world had for some years been in Lowood; her experience had been of its rules and systems. Now, she remembered that the real world was wide and that a varied field of hopes and fears, of sensations and excitements, awaited those who had courage to go forth into its expanse, to seek real knowledge of life amidst its perils.

Jane went to her window, opened it and looked out. There were the two wings of the building; there was the garden; there were the skirts of Lowood; there was the hilly horizon. Her eyes passed all other objects to rest on those most remote, the blue peaks; it was those she longed to surmount; all within their boundary of rock and heath seemed prison-ground, exile limits. She traced the white road winding round the base of one mountain and vanishing in a gorge between two.

She recalled the time when she had travelled that very road in a coach; she remembered descending that hill at twilight; an age seemed to have elapsed since the day which brought her first to Lowood. She had never quit it since. She spent all her vacations at school. Mrs Reed had never sent for her to Gateshead; neither she nor any of her family had ever been to visit her. She had had no communication by letter or message with the outer world—school rules, school duties, school habits and notions, voices and faces, phrases, costumes, preferences and antipathies and such was what she knew of existence.

And now she felt that it was not enough. She tired of the routine of eight years in one afternoon. She denied liberty; for liberty she gasped; for liberty she uttered a prayer. It seemed scattered on the wind that was faintly blowing. She abandoned it and framed a humbler supplication; for change, stimulus: that petition, too, seemed swept off into vague space. All of a sudden, she cried, half desperate, ‘Grant me at least a new servitude.’

A bell, ringing the hour of supper, called her downstairs. She was not free to resume the interrupted chain of her reflections till bedtime. Even then a teacher who occupied the same room with her kept her from the subject to which she longed to recur, by a prolonged effusion of small talk. The teacher’s name was Miss Gryce. She snored at last; she was a heavy Welshwoman.

Till now, her habitual nasal strains had never been regarded by Jane in any other light than as a nuisance. Jane sat up in bed by way of arousing the heavy Welshwoman. It was a chilly night. Jane covered her shoulders with a shawl. Then, she proceeded to think again with all her might. ‘What do I want—a new place in a new house, amongst new faces, under new circumstances? I want this because it is of no use wanting anything better. How do people do to get a new place? They apply to friends, I suppose. But I have no friends. There are many others who have no friends, who must look about for, themselves and be their own helpers.’

She could not tell; nothing answered her. Then, she ordered her brain to find a response quickly. It worked faster and faster. She felt the pulses throb in her head and temples. For nearly an hour or so, it worked in chaos. No result came of its efforts. Feverish with vain labour, she got up and took a turn in the room. She under the curtain, noted a star or two, shievered with cold and crept into bed.

Jane Eyre had become mature as a teacher as she had been teaching there for two years. She had been getting only fifteen pounds per annum. One day, she decided to leave Lowood school. She wrote an advertisement. She sent it to the editor of the Herald to be published in the newspaper for a situation in a family where the children were under fourteen. To her amazement, Jane received a reply within a fortnight from Mrs Fairfax, Thornfield, near Millcote. Jane went through the reply for a long time.

The writing was old-fashioned and rather uncertain, like that of an elderly lady. This circumstance was satisfactory. A private fear had haunted Jane, that in thus acting for herself and by her own guidance, she ran the risk of getting into some scrape. Above all things, she wished the result of her endeavours to be respectable and proper. She now felt that an elderly lady was no bad ingredient in the business she had on hand. She saw Mrs Fairfax in a black gown and widow’s cap; frigid perhaps, but not uncivil, a model of elderly English respectability. Thornfield was the name of her house. It was a neat orderly spot. Jane Eyre had a prosper of getting a new situation where the salary would be double what she now received at Lowood.

As requested by Mrs Fairfax, Jane sent her references and address to her by post. Then, she told the then superintendent about her new situation. Permission was granted to Jane only after consulting Mr Brocklehurst. Jane Eyre got busy with her preparations. In the evening, Bessie, the nurse, came over there to meet Jane who welcomed her warmly. Bessie married a coachman five years ago. She told Jane about Mrs Reed and her family. Jane had not received a single call from Mrs Reed during her eight long years at Lowood school. Both Jane and Bessie talked to each other about old times a lot in the bed at night.

Jane now busied herself in preparations; the fortnight passed rapidly. She had not a very large wardrobe. though it was adequate to her wants. Then, she packed her trunk, the same trunk she had brought with her eight years ago from Gateshead.

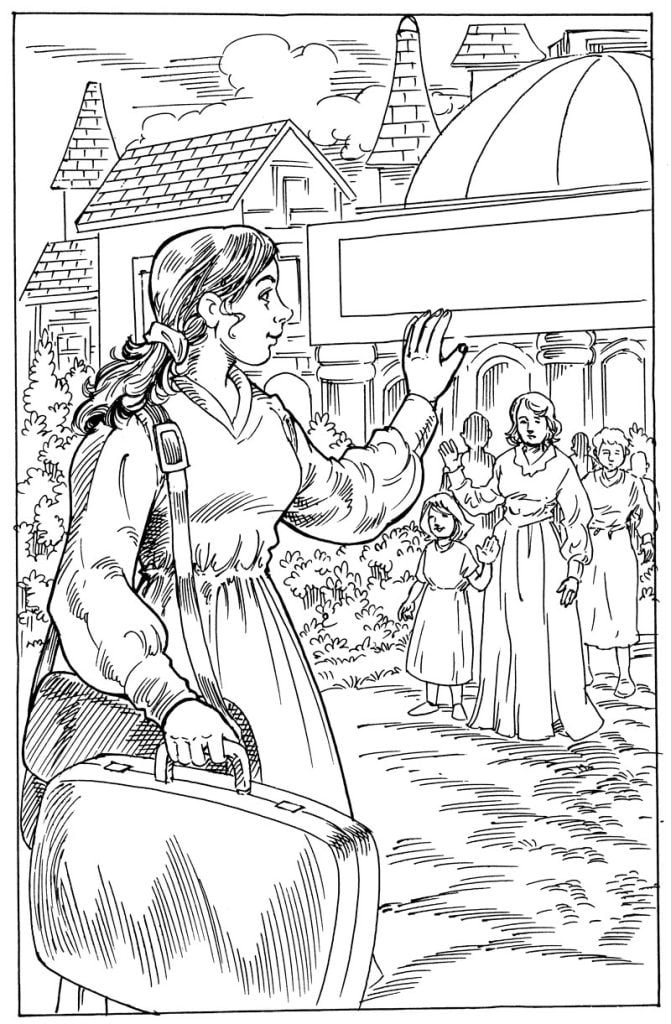

Next day, each of them went her separate way with a heavy heart. A coach arrived at the gate of Lowood school and Jane Eyre bade goodbye to the entire school.