Chapter-8

Little Adele was docile as well as a lively child. She made good progress. Both Jane and her were comfortable in each other’s company. The other members of Thornfield Hall—John and his wife, Leah the housemaid and Sophie, little Adele’s French attendant—were decent people. One day, Mrs Fairfax wrote a letter. It was to be posted. But there was none except Jane in Thornfield Hall. Jane told Mrs Fairfax that she would post the letter. Mrs Fairfax handed the letter across to Jane. It was afternoon. Jane went out of Thornfield Hall. She got onto the path which led to the post-box. There were fields on either side of the path.

The ground was hard, the air was still and her road was lonely. She walked fast till she got warm. Then, she walked slowly to enjoy and analyse the species of pleasure brooding for her in the hour and situation. It was three o’ clock. The church bell rolled as she passed under the belfry. The charm of the hour lay in its approaching dimness, in the low-gliding and pale-bearing sun. She was a mile from Thornfield in a lane noted for wild roses in summer, for nuts and blackberries in autumn, and even now possessing a few coral treasures in hips and haws. Far and wide, on each side, there were only fields, where no cattle now browsed. The little brown birds, which stirred occasionally in the hedge, looked like single russet leaves that had forgotten to drop.

This lane inclined up-hill all the way to Hay. Having reached the middle, she sat down on a stile which led thence into a field. Gathering her mantle about her, and sheltering her hands in her muff, she did not feel the cold, though it froze keenly; as was attested by a sheet of ice covering the causeway, where a little brooklet, now congealed, had overflowed after a rapid thaw some days since. From her seat she could look down on Thornfield; the gray and battlemented hall was the principal object in the vale below her; its woods and dark rookery rose against the west. She lingered till the sun went down amongst the trees, and sank crimson and clear behind them. She then turned eastward.

On the hill-top above her sat the rising moon; pale yet as a cloud, but brightening momentarily, she looked over Hay, which, half lost in trees, sent up a blue smoke from its few chimneys; it was yet a mile distant, but in the absolute hush she could hear plainly its thin murmurs of life. Her ear, too, felt the flow of currents; in what dales and depths she could not tell; but there were many hills beyond Hay, and doubtless many becks threading their passes. That evening calm betrayed like the tinkle of the nearest streams, the sough of the most remote. A rude noise broke on these fine ripplings and whisperings, at once so far away and so clear; a positive tramp, a metallic clatter, which effaced the soft wave-wanderings; as, in a picture, the solid mass of a crag, or the rough boles of a Greek oak, drawn in dark and strong on the foreground, efface the aerial distance of azure hill, sunny horizon, and blended clouds where tint melts into tint.

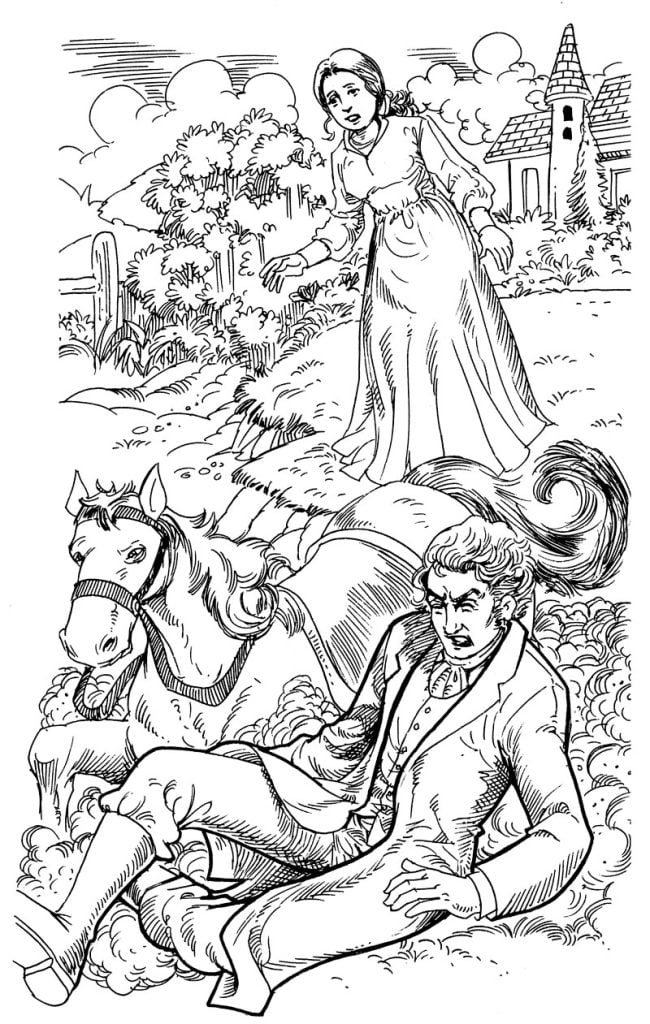

All of a sudden, Jane saw a horse approaching. It was a tall horse and had a rider on its back. As the horse went past Jane, she heard something fall. She, at once, turned around. The horse had slipped on ice. Its rider had fallen off. He was unable to get up. When Jane saw this, she rushed towards the rider. Going up to him Jane said to him, “Sir! are you all right? May I help you get up.” The rider had a dark face with chiselled features. He was of middle height and had a broad chest. He was almost thirty-five years of age.

He retorted, “Just stand on one side. I know how to rise.” Jane stood aghast. She wanted to offer a helping hand to the rider. When the rider got up completely, he said to Jane, “Where do you live?”

Jane, at once, said, “At Thornfield Hall.”

Then the rider remarked further, “Who is the owner of Thornfield?”

Jane replied, “Mr Rochester.”

The rider said, “Do you know Mr Rochester?”

Jane replied humbly, “I have never seen him since I joined Thornfield Hall as a governess.” Saying these words, Jane was on her way to post the letter. She had requested the rider to wait there till she returned. When she came back there, the rider was nowhere to be seen. Feeling disappointed and unhappy, she returned to Thornfield Hall. Reaching there she came to learn that the rider who fell off his horse was none other than Mr Rochester.

In the evening, Mrs Fairfax introduced Jane Eyre to Mr Rochester. Jane Eyre told Mrs Fairfax that she had already met Mr Rochester. Then, she narrated the entire incident to Mrs Fairfax. After some time, Mrs Fairfax went away from there leaving Jane Eyre with Mr Rochester. After tea, Mr Rochester asked Jane about her family and past life. Jane told him that she had neither parents nor brothers nor sisters. She narrated her life at Lowood school to him. Then, Mr Rochester said to Jane, “O dear governess! you have really worked hard. Adele has made much improvement under your able guidance. I am proud of you. I honour your sincere efforts.”

Saying these words, he told Jane that he had fallen in love with Adele’s mother, Celine Varens, when he was young. Celine was an opera dancer. She proved to be unfaithful to him. She had a daughter from other man. To shun infamy, she abandoned little Adele and went away from my life for ever.

Then, Mr Rochester started sobbing. After a while, he resumed, “Dear Jane! I brought little Adele to Thornfield to be reared in England. I didn’t want the world to label her as a forsaken child.”

Jane Eyre felt very miserable having heard the pathetic tale of Mr Rochester. She decided to give more affection to Adele. Her heart was bubbling with the milk of human kindness.

Days passed by, followed by weeks and months. The confidence Mr Rochester had reposed in her brought her closer to him. The behaviour of Mr Rochester towards Jane grew friendly and pleasant. He talked to Jane in a refined manner. Jane, too, was always eager to see and meet him.