Chapter 9

One day, Clover and Elsie were busy downstairs, they were startled by the sound of Katy’s bell ringing in a sudden and agitated manner. Both ran up two steps at a time, to see what was wanted.

Katy sat in her chair, looking very much flushed and excited.

“Oh, girls!” she exclaimed, “what do you think? I stood up!”

“What?” cried Clover and Elsie.

“I really did! I stood up on my feet! by myself!”

The others were too much astonished to speak, so Katy went on explaining.

“It was all at once, you see. Suddenly, I had the feeling that if I tried I could, and almost before I thought, I did try, and there I was, up and out of the chair. Only I kept hold of the arm all the time! I don’t know how I got back, I was so frightened. Oh, girls!”—and Katy buried her face in her hands.

“Do you think I shall ever be able to do it again?” she asked, looking up with wet eyes.

“Why, of course you will!” said Clover; while Elsie danced about, crying out anxiously: “Be careful! Do be careful!”

Katy tried, but the spring was gone. She could not move out of the chair at all. She began to wonder if she had dreamed the whole thing.

But next day, when Clover happened to be in the room, she heard a sudden exclamation, and turning, there stood Katy, absolutely on her feet.

“Papa! papa!” shrieked Clover, rushing down stairs. “Dorry, John, Elsie—come! Come and see!”

Papa was out, but all the rest crowded up at once. This time Katy found no trouble in “doing it again.” It seemed as if her will had been asleep; and now that it had waked up, the limbs recognized its orders and obeyed them.

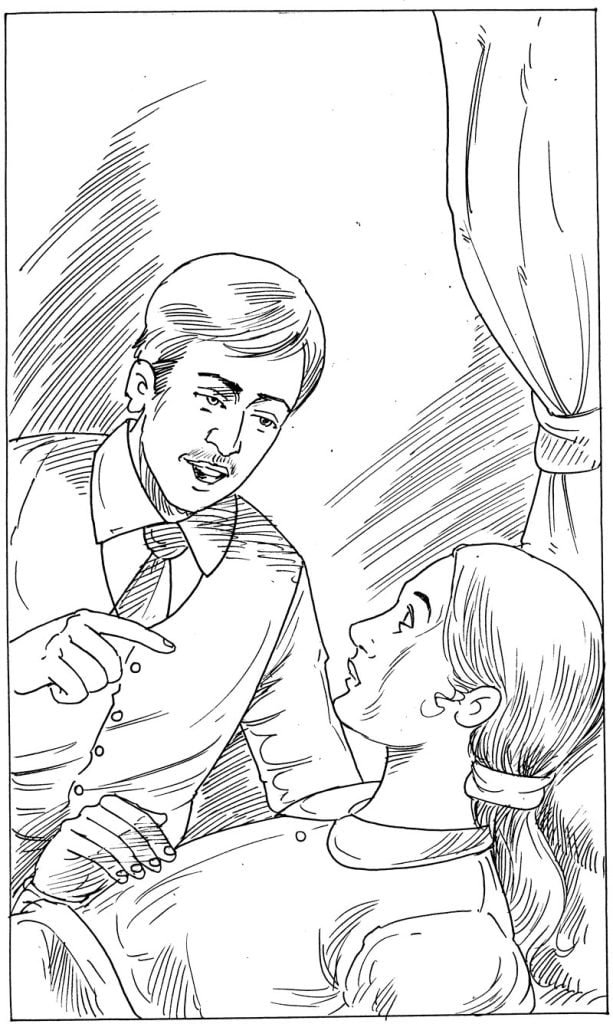

When Papa came in, he was as much excited as any of the children. He walked round and round the chair, questioning Katy and making her stand up and sit down.

“Am I really going to get well?” she asked, almost in a whisper.

“Yes, my love, I think you are,” replied Dr. Carr, seizing Phil and giving him a toss into the air. None of the children had ever before seen Papa behave so like a boy. But pretty soon, noticing Katy’s burning cheeks and excited eyes, he calmed himself, sent the others all away, and sat down to soothe and quiet her with gentle words.

“I think it is coming, my darling,” he said, “but it will take time, and you must have a great deal of patience. After being such a good child all the years, I am sure you won’t fail now. Remember, any imprudence will put you back. You must be content to gain a very little at a time. There is no royal road to walking any more than there is to learning. Every baby finds that out.”

“Oh, Papa!” said Katy, “it’s no matter if it takes a year—if only I get well at last.”

How happy she was that night—too happy to sleep. Papa noticed the dark circles under her eyes in the morning, and shook his head.

“You must be careful,” he told her, “or you’ll be laid up again. A course of fever would put you back for years.”

Katy knew Papa was right, and she was careful, though it was by no means easy to be so with that new life tingling in every limb. Her progress was slow, as Dr. Carr had predicted. At first she only stood on her feet a few seconds, then a minute, then five minutes, holding tightly all the while by the chair. Next she ventured to let go the chair, and stand alone. After that she began to walk a step at a time, pushing a chair before her, as children do when they are learning the use of their feet. Clover and Elsie hovered about her as she moved, like anxious mammas. It was droll, and a little pitiful, to see tall Katy with her feeble, unsteady progress, and the active figures of the little sisters following her protectingly. But Katy did not consider it either droll or pitiful; to her it was simply delightful—the most delightful thing possible. No baby of a year old was ever prouder of his first steps than she.

Gradually she grew adventurous, and ventured on a bolder flight. Clover, running up stairs one day to her own room, stood transfixed at the sight of Katy sitting there, flushed, panting, but enjoying the surprise she caused.

“You see,” she explained, in an apologizing tone, “I was seized with a desire to explore. It is such a time since I saw any room but my own! But oh dear, how long that hall is! I had forgotten it could be so long. I shall have to take a good rest before I go back.”

Katy did take a good rest, but she was very tired next day. The experiment, however, did no harm. In the course of two or three weeks, she was able to walk all over the second story.

This was a great enjoyment. It was like reading an interesting book to see all the new things, and the little changes. She was forever wondering over something.

“Why, Dorry,” she would say, “what a pretty book-shelf! When did you get it?”

“That old thing! Why, I’ve had it two years. Didn’t I ever tell you about it?”

“Perhaps you did,” Katy would reply, “but you see I never saw it before, so it made no impression.”

By the end of August she was grown so strong, that she began to talk about going down stairs. But Papa said, “Wait.”

“It will tire you much more than walking about on a level,” he explained, “you had better put it off a little while—till you are quite sure of your feet.”

“I think so too,” said Clover; “and beside, I want to have the house all put in order and made nice, before your sharp eyes see it, Mrs. Housekeeper. Oh, I’ll tell you! Such a beautiful idea has come into my head! You shall fix a day to come down, Katy, and we’ll be all ready for you, and have a ‘celebration’ among ourselves. That would be just lovely! How soon may she, Papa?”

“Well—in ten days, I should say, it might be safe.”

“Ten days! that will bring it to the seventh of September, won’t it?” said Katy. “Then Papa, if I may, I’ll come down stairs the first time on the eighth. It was Mamma’s birthday, you know,” she added in a lower voice.

So it was settled. “How delicious!” cried Clover, skipping about and clapping her hands: “I never, never, never did hear of anything so perfectly lovely. Papa, when are you coming down stairs? I want to speak to you dreadfully.”

“Right away—rather than have my coat-tails pulled off,” answered Dr. Carr, laughing, and they went away together. Katy sat looking out of the window in a peaceful, happy mood.

“Oh!” she thought, “can it really be? Is School going to ‘let out,’ just as cousin Helen’s hymn said? Am I going to ‘Bid a sweet good-bye to Pain?’ But there was Love in the Pain. I see it now. How good the dear Teacher has been to me!”

Clover seemed to be very busy all the rest of that week. She was “having windows washed,” she said, but this explanation hardly accounted for her long absences, and the mysterious exultation on her face, not to mention certain sounds of hammering and sawing which came from down stairs. The other children had evidently been warned to say nothing; for once or twice Philly broke out with, “Oh, Katy!” and then hushed himself up, saying, “I ‘most forgot!” Katy grew very curious. But she saw that the secret, whatever it was, gave immense satisfaction to everybody except herself; so, though she longed to know, she concluded not to spoil the fun by asking any questions.

At last it wanted but one day of the important occasion.

“See,” said Katy, as Clover came into the room a little before tea-time. “Miss Petingill has brought home my new dress. I’m going to wear it for the first time to go down stairs in.”

“How pretty!” said Clover, examining the dress, which was a soft, dove-colored cashmere, trimmed with ribbon of the same shade. “But Katy, I came up to shut your door. Bridget’s going to sweep the hall, and I don’t want the dust to fly in, because your room was brushed this morning, you know.”

“What a queer time to sweep a hall!” said Katy, wonderingly. “Why don’t you make her wait till morning?”

“Oh, she can’t! There are—she has—I mean there will be other things for her to do to-morrow. It’s a great deal more convenient that she should do it now. Don’t worry, Katy, darling, but just keep your door shut. You will, won’t you? Promise me!”

“Very well,” said Katy, more and more amazed, but yielding to Clover’s eagerness, “I’ll keep it shut.” Her curiosity was excited. She took a book and tried to read, but the letters danced up and down before her eyes, and she couldn’t help listening. Bridget was making a most ostentatious noise with her broom, but through it all, Katy seemed to hear other sounds—feet on the stairs, doors opening and shutting—once, a stifled giggle. How queer it all was!

“Never mind,” she said, resolutely stopping her ears, “I shall know all about it to-morrow.”

To-morrow dawned fresh and fair—the very ideal of a September day.

“Katy!” said Clover, as she came in from the garden with her hands full of flowers, “that dress of yours is sweet. You never looked so nice before in your life!” And she stuck a beautiful carnation pink under Katy’s breast-pin and fastened another in her hair.

“There!” she said, “now you’re adorned. Papa is coming up in a few minutes to take you down.”

Just then Elsie and Johnnie came in. They had on their best frocks. So had Clover. It was evidently a festival-day to all the house. Cecy followed, invited over for the special purpose of seeing Katy walk down stairs. She, too, had on a new frock.

“How fine we are!” said Clover, as she remarked this magnificence. “Turn round, Cecy—a panier, I do declare—and a sash! You are getting awfully grown up, Miss Hall.”

“None of us will ever be so ‘grown up’ as Katy,” said Cecy, laughing.

And now Papa appeared. Very slowly they all went down stairs, Katy leaning on Papa, with Dorry on her other side, and the girls behind, while Philly clattered ahead. And there were Debby and Bridget and Alexander, peeping out of the kitchen door to watch her, and dear old Mary with her apron at her eyes crying for joy.

“Oh, the front door is open!” said Katy, in a delighted tone. “How nice! And what a pretty oil-cloth. That’s new since I was here.”

“Don’t stop to look at that!” cried Philly, who seemed in a great hurry about something. “It isn’t new. It’s been there ever and ever so long! Come into the parlor instead.”

“Yes!” said Papa, “dinner isn’t quite ready yet, you’ll have time to rest a little after your walk down stairs. You have borne it admirably, Katy. Are you very tired?”

“Not a bit!” replied Katy, cheerfully. “I could do it alone, I think. Oh! the bookcase door has been mended! How nice it looks.”

“Don’t wait, oh, don’t wait!” repeated Phil, in an agony of impatience.

So they moved on. Papa opened the parlour door. Katy took one step into the room—then stopped. The color flashed over her face, and she held by the door-knob to support herself. What was it that she saw?

Not merely the room itself, with its fresh muslin curtains and vases of flowers. Nor even the wide, beautiful window which had been cut towards the sun, or the inviting little couch and table which stood there, evidently for her. No, there was something else! The sofa was pulled out and there upon it, supported by pillows, her bright eyes turned to the door, lay—cousin Helen! When she saw Katy, she held out her arms.

Clover and Cecy agreed afterward that they never were so frightened in their lives as at this moment; for Katy, forgetting her weakness, let go of Papa’s arm, and absolutely ran toward the sofa. “Oh, cousin Helen! dear, dear Cousin Helen!” she cried. Then she tumbled down by the sofa somehow, the two pairs of arms and the two faces met, and for a moment or two not a word more was heard from anybody.

“Isn’t a nice ‘prise?” shouted Philly, turning a somerset by way of relieving his feelings, while John and Dorry executed a sort of war-dance round the sofa.

Phil’s voice seemed to break the spell of silence, and a perfect hubbub of questions and exclamations began.

It appeared that this happy thought of getting cousin Helen to the “Celebration,” was Clover’s. She it was who had proposed it to Papa, and made all the arrangements. And, artful puss! she had set Bridget to sweep the hall, on purpose that Katy might not hear the noise of the arrival.

“Cousin Helen’s going to stay three weeks this time—isn’t that nice?” asked Elsie, while Clover anxiously questioned: “Are you sure that you didn’t suspect? Not one bit? Not the least tiny, weeny mite?”

“No, indeed—not the least. How could I suspect anything so perfectly delightful?” And Katy gave cousin Helen another rapturous kiss.

Such a short day as that seemed! There was so much to see, to ask about, to talk over, that the hours flew, and evening dropped upon them all like another great surprise.

Cousin Helen was perhaps the happiest of the party. Beside the pleasure of knowing Katy to be almost well again, she had the additional enjoyment of seeing for herself how many changes for the better had taken place, during the four years, among the little cousins she loved so much.

It was very interesting to watch them all. Elsie and Dorry seemed to her the most improved of the family. Elsie had quite lost her plaintive look and little injured tone, and was as bright and beaming a maiden of twelve as any one could wish to see. Dorry’s moody face had grown open and sensible, and his manners were good-humored and obliging. He was still a sober boy, and not specially quick in catching an idea, but he promised to turn out a valuable man. And to him, as to all the other children, Katy was evidently the centre and the sun. They all revolved about her, and trusted her for everything. Cousin Helen looked on as Phil came in crying, after a hard tumble, and was consoled; as Johnnie whispered an important secret, and Elsie begged for help in her work. She saw Katy meet them all pleasantly and sweetly, without a bit of the dictatorial elder-sister in her manner, and with none of her old, impetuous tone. And best of all, she saw the change in Katy’s own face: the gentle expression of her eyes, the womanly look, the pleasant voice, the politeness, the tact in advising the others, without seeming to advise.

“Dear Katy,” she said a day or two after her arrival, “this visit is a great pleasure to me—you can’t think how great. It is such a contrast to the last I made, when you were so sick, and everybody so sad. Do you remember?”

“Indeed I do! And how good you were, and how you helped me! I shall never forget that.”

“I’m glad! But what I could do was very little. You have been learning by yourself all this time. And Katy, darling, I want to tell you how pleased I am to see how bravely you have worked your way up. I can perceive it in everything—in Papa, in the children, in yourself. You have won the place, which, you recollect, I once told you an invalid should try to gain, of being to everybody ‘The Heart of the House.’”

“Oh, cousin Helen, don’t!” said Katy, her eyes filling with sudden tears. “I haven’t been brave. You can’t think how badly I sometimes have behaved—how cross and ungrateful I am, and how stupid and slow. Every day I see things which ought to be done, and I don’t do them. It’s too delightful to have you praise me—but you mustn’t. I don’t deserve it.”

But although she said yet she didn’t deserve it. I think that Katy did!

❒