Chapter 7

In the dawn,’ the lama went on more gravely, ready rosary clicking between the slow sentences, ‘came enlightenment. It is here … I am an old man … hill-bred, hill-fed, never to sit down among my Hills. Three years I travelled through Hind, but—can earth be stronger than Mother Earth? My stupid body yearned to the Hills and the snows of the Hills, from below there. I said, and it is true, my Search is sure. So, at the Kulu woman’s house I turned hillward, over-persuaded by myself.

There is no blame to the hakim. He—following Desire—foretold that the Hills would make me strong. They strengthened me to do evil, to forget my Search. I delighted in life and the lust of life. I desired strong slopes to climb. I cast about to find them. I measured the strength of my body, which is evil, against the high Hills, I made a mockery of you when you breath came short under Jamnotri. I jested when you would not face the snow of the pass.’

‘But what harm? I was afraid. It was just. I am not a hillman; and I loved you for your new strength.’

‘More than once I remember’—he rested his cheek dolefully on his hand—‘I sought your praise and the hakim’s for the mere strength of my legs. Thus evil followed evil till the cup was full. Just is the Wheel! All Hind for three years did me all honour. From the Fountain of Wisdom in the Wonder House to’—he smiled—’a little child playing by a big gun—the world prepared my road. And why?’

‘Because we loved you. It is only the fever of the blow. I myself am still sick and shaken.’

‘No! It was because I was upon the Way—tuned as are si-nen [cymbals] to the purpose of the Law. I departed from that ordinance. The tune was broken: followed the punishment. In my own Hills, on the edge of my own country, in the very place of my evil desire, comes the buffet—here!’ (He touched his brow.) ‘As a novice is beaten when he misplaces the cups, so am I beaten, who was Abbot of Such-zen. No word, look you, but a blow, chela.’

‘But the Sahibs did not know thee, Holy One?’

‘We were well matched. Ignorance and Lust met Ignorance and Lust upon the road, and they begat Anger. The blow was a sign to me, who am no better than a strayed yak, that my place is not here. Who can read the Cause of an act is halfway to Freedom! “Back to the path,” says the Blow. “The Hills are not for thee. Thou canst not choose Freedom and go in bondage to the delight of life.”’

‘Would we had never met that cursed Russian!’

‘Our Lord Himself cannot make the Wheel swing backward. And for my merit that I had acquired I gain yet another sign.’ He put his hand in his bosom, and drew forth the Wheel of Life. ‘Look! I considered this after I had meditated. There remains untorn by the idolater no more than the breadth of my fingernail.’

‘I see.’

‘So much, then, is the span of my life in this body.

I have served the Wheel all my days. Now the Wheel serves me. But for the merit I have acquired in guiding thee upon the Way, there would have been added to me yet another life ere I had found my River. Is it plain, chela?’

Kim stared at the brutally disfigured chart. From left to right diagonally the rent ran—from the Eleventh House where Desire gives birth to the Child (as it is drawn by Tibetans)—across the human and animal worlds, to the Fifth House—the empty House of the Senses. The logic was unanswerable.

‘Before our Lord won Enlightenment’—the lama folded all away with reverence—’He was tempted. I too have been tempted, but it is finished. The Arrow fell in the Plains—not in the Hills. Therefore, what make we here?’

‘Shall we at least wait for the hakim?’

‘I know how long I shall live in this body. What can a hakim do?’

‘But you are all sick and shaken. Thou canst not walk.’

‘How can I be sick if I see Freedom?’ He rose unsteadily to his feet.

‘Then I must get food from the village. Oh, the weary Road!’ Kim felt that he too needed rest.

‘That is lawful. Let us eat and go. The Arrow fell in the Plains … but I yielded to Desire. Make ready, chela.’

Kim turned to the woman with the turquoise headgear who had been idly pitching pebbles over the cliff. She smiled very kindly.

‘I found him like a strayed buffalo in a cornfield—the Babu; snorting and sneezing with cold. He was so hungry that he forgot his dignity and gave me sweet words. The Sahibs have nothing.’ She flung out an empty palm. ‘One is very sick about the stomach. Thy work?’

Kim nodded, with a bright eye.

‘I spoke to the Bengali first—and to the people of a near-by village after. The Sahibs will be given food as they need it—nor will the people ask money. The plunder is already distributed. The Babu makes lying speeches to the Sahibs. Why does he not leave them?’

‘Out of the greatness of his heart.’

‘Was never a Bengali yet had one bigger than a dried walnut. But it is no matter … Now as to walnuts. After service comes reward. I have said the village is thine.’

‘It is my loss,’ Kim began. ‘Even now I had planned desirable things in my heart which’—there is no need to go through the compliments proper to these occasions. He sighed deeply … ‘But my master, led by a vision—’

‘Huh! What can old eyes see except a full begging-bowl?’

‘—turns from this village to the Plains again.’

‘Bid him stay.’

Kim shook his head. ‘I know my Holy One, and his rage if he be crossed,’ he replied impressively. ‘His curses shake the Hills.’

‘Pity they did not save him from a broken head! I heard that thou wast the tiger-hearted one who smote the Sahib. Let him dream a little longer. Stay!’

‘Hillwoman,’ said Kim, with austerity that could not harden the outlines of his young oval face, ‘these matters are too high for thee.’

‘The Gods be good to us! Since when have men and women been other than men and women?’

‘A priest is a priest. He says he will go upon this hour. I am his chela, and I go with him. We need food for the Road. He is an honoured guest in all the villages, but’—he broke into a pure boy’s grin—’the food here is good. Give me some.’

‘What if I do not give it thee? I am the woman of this village.’

‘Then I curse you—a little—not greatly, but enough to remember.’ He could not help smiling.

‘Thou hast cursed me already by the down-dropped eyelash and the uplifted chin. Curses? What should I care for mere words?’ She clenched her hands upon her bosom … ‘But I would not have thee to go in anger, thinking hardly of me—a gatherer of cow-dung and grass at Shamlegh, but still a woman of substance.’

‘I think nothing,’ said Kim, ‘but that I am grieved to go, for I am very weary; and that we need food. Here is the bag.’

The woman snatched it angrily. ‘I was foolish,’ said she. ‘Who is thy woman in the Plains? Fair or black? I was fair once. Once, long ago, if you can believe, a Sahib looked on me with favour. Once, long ago, I wore European clothes at the Mission-house yonder.’ She pointed towards Kotgarh. ‘Once, long ago. I was Ker-lis-ti-an and spoke English—as the Sahibs speak it. Yes. My Sahib said he would return and wed me—yes, wed me. He went away—I had nursed him when he was sick—but he never returned. Then I saw that the gods of the Kerlistians lied, and I went back to my own people … I have never set eyes on a Sahib since.

The fit is past, little priestling. Your face and your walk and thy fashion of speech put me in mind of my Sahib, though you are only a wandering mendicant to whom I give a dole. Curse me? You can neither curse nor bless!’ She set her hands on her hips and laughed bitterly.

‘You Gods are lies; your works are lies; your words are lies. There are no Gods under all the Heavens. I know it … But for awhile I thought it was my Sahib come back, and he was my God. Yes, once I made music on a pianno in the Mission-house at Kotgarh. Now I give alms to priests who are heatthen.’ She wound up with the English word, and tied the mouth of the brimming bag.

‘I wait for thee, chela,’ said the lama, leaning against the door-post.

The woman swept the tall figure with her eyes. ‘He walk! He cannot cover half a mile. Whither would old bones go?’

At this Kim, already perplexed by the lama’s collapse and foreseeing the weight of the bag, fairly lost his temper.

‘What is it to thee, woman of ill-omen, where he goes?’

‘Nothing—but something to you, priest with a Sahib’s face. Wilt you carry him on thy shoulders?’

‘I go to the Plains. None must hinder my return. I have wrestled with my soul till I am strengthless. The stupid body is spent, and we are far from the Plains.’

‘Behold!’ she said simply, and drew aside to let Kim see his own utter helplessness. ‘Curse me. Maybe it will give him strength. Make a charm! Call on your great God. You are a priest.’ She turned away.

The lama had squatted limply, still holding by the door-post. One cannot strike down an old man that he recovers again like a boy in the night. Weakness bowed him to the earth, but his eyes that hung on Kim were alive and imploring.

‘It is all well,’ said Kim. ‘It is the thin air that weakens you. In a little while we go! It is the mountain-sickness. I too am a little sick at stomach,’—and he knelt and comforted with such poor words as came first to his lips. Then the woman returned, more erect than ever.

‘You gods useless, heh? Try mine. I am the Woman of Shamlegh.’ She hailed hoarsely, and there came out of a cow-pen her two husbands and three others with a dooli, the rude native litter of the Hills, that they use for carrying the sick and for visits of state. ‘These cattle’—she did not condescend to look at them—’are thine for so long as you shall need.’

‘But we will not go Simla-way. We will not go near the Sahibs,’ cried the first husband.

‘They will not run away as the others did, nor will they steal baggage. Two I know for weaklings. Stand to the rear-pole, Sonoo and Taree.’ They obeyed swiftly. ‘Lower now, and lift in that holy man. I will see to the village and your virtuous wives till ye return.’

‘When will that be?’

‘Ask the priests. Do not pester me. Lay the food-bag at the foot, it balances better so.’

‘Oh, Holy One, thy Hills are kinder than our Plains!’ cried Kim, relieved, as the lama tottered to the litter. ‘It is a very king’s bed—a place of honour and ease. And we owe it to—’

‘A woman of ill-omen. I need your blessings as much as I do your curses. It is my order and none of yours. Lift and away! Here! Have you money for the road?’

She beckoned Kim to her hut, and stooped above a battered English cash-box under her cot.

‘I do not need anything,’ said Kim, angered where he should have been grateful. ‘I am already rudely loaded with favours.’

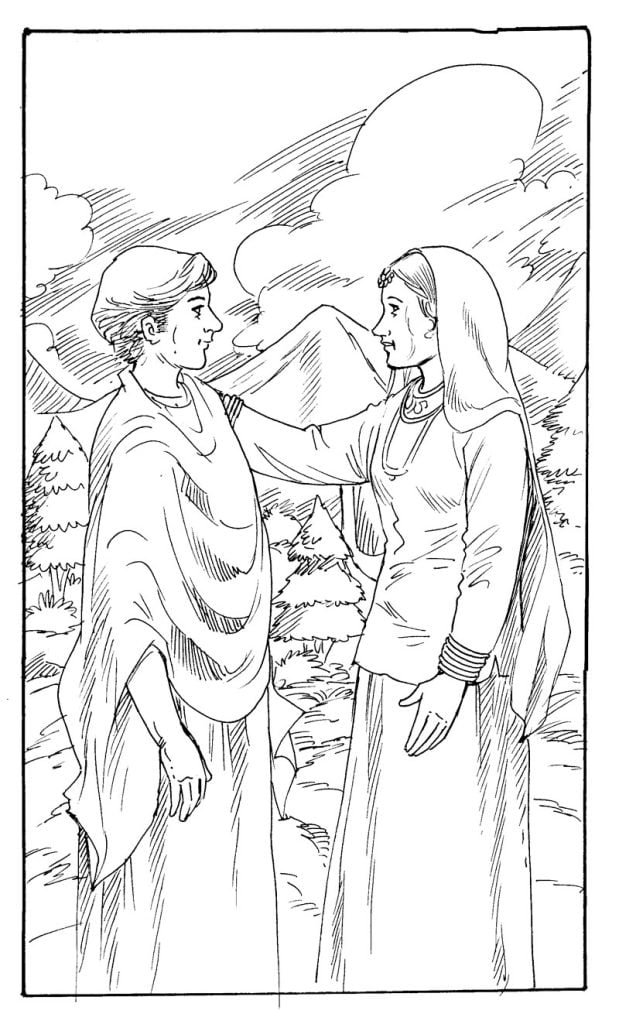

She looked up with a curious smile and laid a hand on his shoulder. ‘At least, thank me. I am foul-faced and a hillwoman, but, as thy talk goes, I have acquired merit. Shall I show thee how the Sahibs render thanks?’ and her hard eyes softened.

‘I am but a wandering priest,’ said Kim, his eyes lighting in answer. ‘You need neither my blessings nor my curses.’

‘Nay. But for one little moment—you can overtake the dooli in ten strides—if you were a Sahib, shall I show you what you would do?’

‘How if I guess, though?’ said Kim, and putting his arm round her waist, he kissed her on the cheek, adding in English: ‘Thank you very much, my dear.’

Kissing is practically unknown among Asiatics, which may have been the reason that she leaned back with wide-open eyes and a face of panic.

‘Next time,’ Kim went on, ‘you must not be so sure of your heatthen priests. Now I say good-bye.’ He held out his hand English-fashion. She took it mechanically. ‘Good-bye, my dear.’

‘Good-bye, and—and’—she was remembering her English words one by one—’you will come back again? Good-bye, and—may God bless you.’

Half an hour later, as the creaking litter jolted up the hill path that leads south-easterly from Shamlegh, Kim saw a tiny figure at the hut door waving a white rag.

‘She has acquired merit beyond all others,’ said the lama. ‘For to set a man upon the way to Freedom is half as great as though she had herself found it.’

‘Umm,’ said Kim thoughtfully, considering the past. ‘It may be that I have acquired merit also … At least she did not treat me like a child.’ He hitched the front of his robe, where lay the slab of documents and maps, re-stowed the precious food-bag at the lama’s feet, laid his hand on the litter’s edge, and buckled down to the slow pace of the grunting husbands.

‘These also acquire merit,’ said the lama after three miles.

‘More than that, they shall be paid in silver,’ quoted Kim. The Woman of Shamlegh had given it to him;