Chapter 6

The next morning, before they had quitted their beds, a messenger arrived with letters from General Middleton, and from him they found that the king’s army had encamped on the evening before not six miles from Portlake. As they hastily dressed themselves, Chaloner proposed to Edward that a little alteration in his dress would be necessary; and taking him to a wardrobe in which had been put aside some suits of his own, worn when he was a younger and slighter-made man than he now was, he requested Edward to make use of them. Edward, who was aware that Chaloner was right in his proposal, selected two suits of colors which pleased him most; and dressing in one, and changing his hat for one more befitting his new attire, was transformed into a handsome Cavalier. As soon as they had broken their fast they took leave of the old ladies, and mounting their horses set off for the camp. An hour’s ride brought them to the outposts; and communicating with the officer on duty, they were conducted by an orderly to the tent of General Middleton, who received Chaloner with great warmth as an old friend, and was very courteous to Edward as soon as he heard that he was the son of Colonel Beverley.

“I have wanted you, Chaloner,” said Middleton; “we are raising a troop of horse; the Duke of Buckingham commands it, but Massey will be the real leader of it; you have influence in this county, and will, I have no doubt, bring us many good hands.”

“Where is the Earl of Derby?”

“Joined us this morning; we have marched so quick that we have not had time to pick our adherents up.”

“And General Leslie?”

“Is by no means in good spirits: why, I know not. We have too many ministers with the army, that is certain, and they do harm; but we can not help ourselves. His majesty must be visible by this time; if you are ready, I will introduce you; and, when that is done, we will talk matters over.”

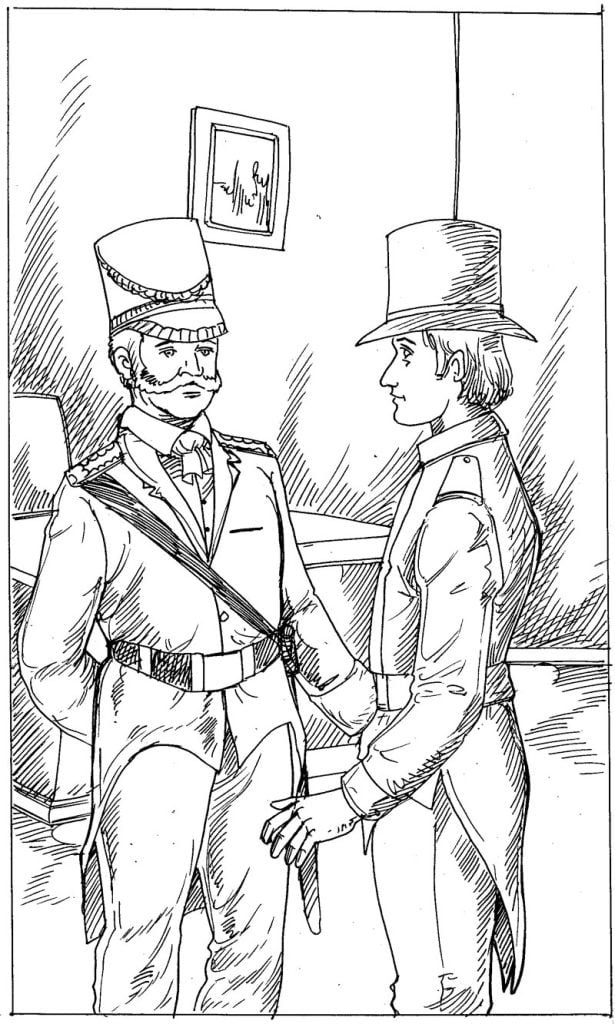

General Middleton then walked with them to the house in which the king had taken up his quarters for the night; and after a few minutes’ waiting in the anteroom, they were admitted into his presence.

“Allow me, your majesty,” said General Middleton, after the first salutations, “to present to you Major Chaloner, whose father’s name is not unknown to you.”

“On the contrary, well known to us,” replied the king, “as a loyal and faithful subject whose loss we must deplore. I have no doubt that his son inherits his courage and his fidelity.”

The king held out his hand, and Chaloner bent his knee and kissed it.

“And now, your majesty will be surprised that I should present to you one of a house supposed to be extinct—the eldest son of Colonel Beverley.”

“Indeed!” replied his majesty; “I heard that all his family perished at the ruthless burning of Arnwood. I hold myself fortunate, as a king, that even one son of so loyal and brave a gentleman as Colonel Beverley has escaped. You are welcome, young sir—most welcome to us; you must be near us; the very name of Beverley will be pleasing to our ears by night or day.”

Edward knelt down and kissed his majesty’s hand, and the king said—

“What can we do for a Beverley? let us know, that we may show our feelings toward his father’s memory.”

“All I request is, that your majesty will allow me to be near you in the hour of danger,” replied Edward.

“A right Beverley reply,” said the king; “and so we shall see to it, Middleton.”

After a few more courteous words from his majesty, they withdrew, but General Middleton was recalled by the king for a minute or two to receive his commands. When he rejoined Edward and Chaloner, he said to Edward—

“I have orders to send in for his majesty’s signature your commission as captain of horse, and attached to the king’s personal staff; it is a high compliment to the memory of your father, sir, and, I may add, your own personal appearance. Chaloner will see to your uniforms and accouterments; you are well mounted, I believe; you have no time to lose, as we march to-morrow for Warrington, in Cheshire.”

“Has any thing been heard of the Parliamentary army?”

“Yes; they are on the march towards London by the Yorkshire road, intending to cut us off if they can. And now, gentlemen, farewell; for I have no idle time, I assure you.”

Edward was soon equipped, and now attended upon the king. When they arrived at Warrington, they found a body of horse drawn up to oppose their passage onward. These were charged, and fled with a trifling loss; and as they were known to be commanded by Lambert, one of Cromwell’s best generals, there was great exultation in the king’s army; but the fact was, that Lambert had acted upon Cromwell’s orders, which were to harass and delay the march of the king as much as possible, but not to risk with his small force any thing like an engagement. After this skirmish it was considered advisable to send back the Earl of Derby and many other officers of importance into Lancashire, that they might collect the king’s adherents in that quarter and in Cheshire. Accordingly the earl, with about two hundred officers and gentlemen, left the army with that intention. It was then considered that it would be advisable to march the army direct to London; but the men were so fatigued with the rapidity of the march up to the present time, and the weather was so warm, that it was decided in the negative; and as Worcester was a town well affected to the king, and the country abounded with provisions, it was resolved that the army should march there, and wait for English re-enforcements. This was done; the city opened the gates with every mark of satisfaction, and supplied the army with all that it required. The first bad news which reached them was the dispersion and defeat of the whole of the Earl of Derby’s party, by a regiment of militia which had surprised them at Wigan during the night, when they were all asleep, and had no idea that any enemy was near to them. Although attacked at such disadvantage, they defended themselves till a large portion of them was killed, and the remainder were taken prisoners, and most of them brutally put to death. The Earl of Derby was made a prisoner, but not put to death with the others.

“This is bad news, Chaloner,” said Edward.

“Yes; it is more than bad,” replied the latter; “we have lost our best officers, who never should have left the army; and now the consequences of the defeat will be, that we shall not have any people come forward to join us. The winning side is the right side in this world; and there is more evil than that; the Duke of Buckingham has claimed the command of the army, which the king has refused, so that we are beginning to fight among ourselves. General Leslie is evidently dispirited, and thinks bad of the cause. Middleton is the only man who does his duty. Depend upon it, we shall have Cromwell upon us before we are aware of it; and we are in a state of sad confusion: officers quarreling, men disobedient, much talking, and little doing. Here we have been five days, and the works which have been proposed to be thrown up as defenses, not yet begun.”

“I can not but admire the patience of the king, with so much to harass and annoy him.”

“He must be patient, perforce,” replied Chaloner; “he plays for a crown, and it is a high stake; but he can not command the minds of men, although he may the persons. I am no croaker, Beverley, but if we succeed with this army, as at present disorganized, we shall perform a miracle.”

“We must hope for the best,” replied Edward; “common danger may cement those who would otherwise be asunder; and when they have the army of Cromwell before them, they may be induced to forget their private quarrels and jealousies, and unite in the good cause.”

“I wish I could be of your opinion, Beverley,” replied Chaloner; “but I have mixed with the world longer than you have, and I think otherwise.”

Several more days passed, during which no defenses were thrown up, and the confusion and quarreling in the army continued to increase, until at last news arrived that Cromwell was within half a day’s march of them, and that he had collected all the militia on his route, and was now in numbers nearly double to those in the king’s army. All was amazement and confusion—nothing had been done—no arrangements had been made—Chaloner told Edward that all was lost if immediate steps were not taken.

On the 3d of October, the army of Cromwell appeared in sight. Edward had been on horseback, attending the king, for the best part of the night; the disposition of the troops had been made as well as it could; and it was concluded, as Cromwell’s army remained quiet, that no attempt would be made on that day. About noon the king returned to his lodging, to take some refreshment after his fatigue. Edward was with him; but before an hour had passed, the alarm came that the armies were engaged. The king mounted his horse, which was ready saddled at the door; but before he could ride out of the city, he was met and nearly beaten back by the whole body almost of his own cavalry, who came running on with such force that he could not stop them. His majesty called to several of the officers by name, but they paid no attention; and so great was the panic, that both the king and his staff, who attended him, were nearly overthrown, and trampled under foot.

Cromwell had passed a large portion of his troops over the river without the knowledge of the opponents, and when the attack was made in so unexpected a quarter, a panic ensued. Where General Middleton and the Duke Hamilton commanded, a very brave resistance was made; but Middleton being wounded, Duke Hamilton having his leg taken off by a round-shot, and many gentlemen having fallen, the troops, deserted by the remainder of the army, at last gave way, and the rout was general, the foot throwing away their muskets before they were discharged.

❒