Chapter 1

Chapter I is taken from the May 3rd and May 4th entries in Jonathan Harker’s journal. Harker is on a business trip in Eastern Europe, making his way across one of the most isolated regions of Europe. He is going to meet a noble of Transylvania, Count Dracula. The heading to his journal entry tells us that Jonathan is writing in Bistritz, in what is now Romania. Two days ago, he was in Munich. One day ago, he was in Vienna. As he has moved farther east, the country has become wilder and less modern. Jonathan Harker records his observations of the people and the countryside, their costumes and customs. He has been instructed to stay at an old-fashioned hotel in Bistritz before setting out for the final leg of the journey to Dracula’s castle. At Bistritz, a letter from Dracula is waiting for him. Jonathan is to rest before setting out the next day for the Borgo Pass, where the Count’s coach will be waiting for him.

The landlord and his wife are visibly distressed by Jonathan’s intentions to go to Dracula’s castle. Although they cannot understand each other’s languages and must communicate in German, the innkeeper passively tries to stop Jonathan by pretending not to understand his requests for a carriage to the Borgo Pass. The landlord’s wife more aggressively tries to dissuade Jonathan, warning him that tomorrow is St. George’s Day, and at midnight on St. George’s Eve evil is at its strongest. When he insists that he must go, she gives him a crucifix. Jonathan accepts the gift, even though, as an English Protestant, he considers crucifixes idolatrous.

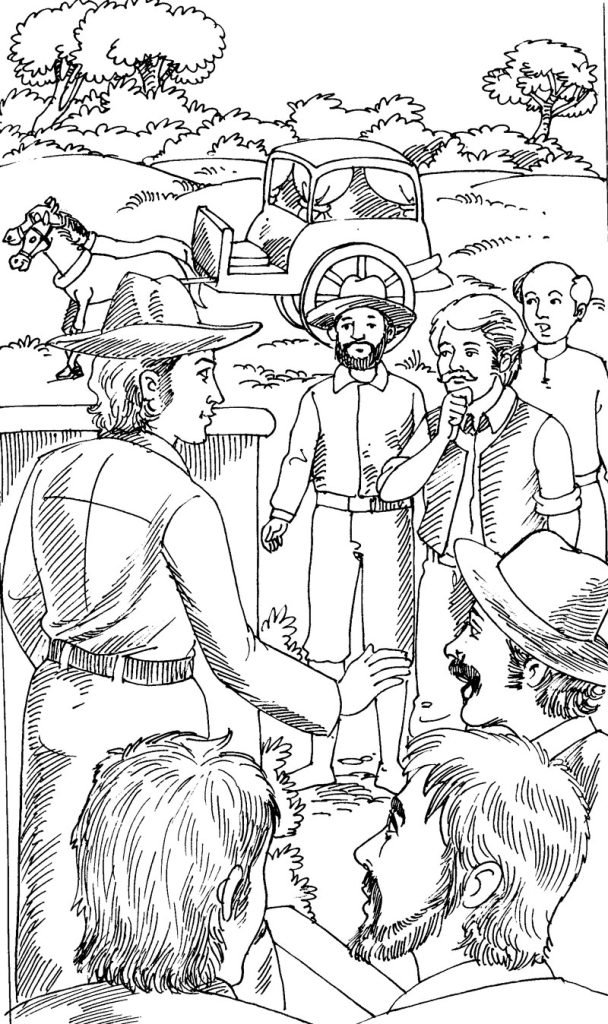

Before Jonathan leaves, he notices that a number of peasants are watching him with apprehension. Although he cannot understand much of their language yet he can make out the words for devil, Satan, werewolf, and vampire. The peasants make motions at him to protect him from the evil eye. On the carriage ride, his fellow passengers, on learning where he is going, treat him with the same kind of concerned sympathy, giving him gifts and protecting him with charms. The ride is in a wild and beautiful country. The carriage driver arrives at the Borgo Pass an hour early, and in bad German he then tries to convince Jonathan that Dracula’s coachman might not come tonight, and Jonathan should come with the rest of them to Bukovina. At that moment, a fearsome-looking coachman arrives on a vehicle pulled by coal-black horses. One of the passengers whispers, “for. He rebukes the carriage driver, and brings Jonathan onto the coach. The final part of the trip is terrifying. The moon is bright but is occasionally obscured by clouds, and strange blue fires and wolves appear along the way. On several occasions, the driver leaves the coach, at which point the wolves come closer and closer to the vehicle. Whenever the driver returns, the wolves flee. The final time this phenomenon occurs; it seems that the wolves flee on the driver’s command. It ends with Dracula’s castle coming into view, its crumbling battlements cutting a jagged line against the night sky.

Taken from the May 5th, 7th, and 8th entries of Jonathan Harker’s journal. Jonathan is dropped off at the great castle of Dracula, where, he is welcomed by the Count himself. The Count is a tall old man, with a white mustache, dressed all in black. Despite the Count’s apparent age, during their handshake Jonathan notices that the Count’s grip is unbelievably strong and that his hand is as cold as a corpse.

Jonathan is shown his room and then brought to a dining room where a fine dinner awaits him. The two men talk, although the Count eats nothing. Jonathan observes him carefully; his face is aquiline, with a high bridge, thin nose, and arched nostrils, a high and round forehead, large eyebrows, scarlet lips, and unusually sharp teeth. His ears are pointed and he is unbelievably pale. At one point, the Count leans in and touches Jonathan; the Englishman is then overcome by nausea, and he cannot explain the source of his revulsion. Dracula also seems to take strange delight in the sound of the howling wolves down in the valley. The two men are still awake at the coming of dawn, when Dracula leaves and tells Jonathan to sleep well and as long as he likes, as the Count must be away until late in the afternoon.

Jonathan sleeps very late into the day, awaking near evening time to take his breakfast. A full meal is waiting for him in the dining room. Dracula is nowhere to be found, but a note tells Jonathan to eat up and await the Count’s return. The house seems to have peculiar shortcomings; there are no servants at all, although the extraordinary furniture and dining set shows that the Count is incredibly wealthy. There are also no mirrors anywhere in the house. Jonathan wanders into a vast library, where he finds many books in English. The Count finds him there, and he grills Jonathan with questions about England. He also desires to speak with Jonathan so that he can improve his English, which he has learnt so far only through books; his desire is to be nothing less than fluent so that he may blend in amongst the English. Through the firm for which Jonathan works, the Count plans to purchase a grand English estate called Carfax. Carfax is a giant, castle-like house built of heavy stones on a large property. It is also near an insane asylum, although Jonathan, like a good businessman, points out that the asylum is not visible from the house. The two men also talk at dinner, during which the Count, once again, does not eat. After dinner, the two men continue to talk, Dracula asking endless questions about England, until once again dawn approaches and the Count ends the discussion and leaves.

Jonathan retires to his room but only sleeps for a few hours. He uses his own small mirror to shave, and when the Count approaches Jonathan from behind Jonathan realizes that the Count has no reflection. Startled, he cuts himself with the razor. He checks again to be sure, and still the Count’s image is absent from the glass. On seeing the blood dripping from Jonathan’s cut, the Count seems to become possessed, clutching Jonathan around the throat, growing calm again only when his hand touches the beads of Jonathan’s crucifix. He cryptically warns Jonathan not to cut himself and then throws the mirror from the window. Jonathan expresses annoyance at the loss of the mirror, wondering how he is to shave without it.

He goes again to the dining room, where breakfast waits for him. The Count is absent. Jonathan wanders around the castle, and he learns that the castle is built on the edge of an enormous precipice. On the south side, the drop from the castle windows is at least a thousand feet. Jonathan keeps wandering, and then he realizes that all of the exits from the castle have been bolted; he is a prisoner in Dracula’s home.

Taken from the May 8th, May 12th, May 15th, and May 16th entries of Jonathan Harker’s journal. When Jonathan realizes he is trapped, he finally is able to realize the danger he is in. He resolves not to tell the Count, because the Count is clearly responsible. Jonathan spies on the Count, watching him make the bed and set the table for dinner. His suspicions that there are no servants are thus confirmed, and Jonathan wonders if the coachman was also Dracula in disguise. He fears the coachman’s power to command the wolves, and the gifts from the peasants (crucifix, garlic, wild rose, and mountain ash) give him some small feeling of comfort.

That night, Dracula recounts the history of the country and of Dracula’s family. There are tales of war and battle against the Turks, with the people of Transylvania united under one of Dracula’s ancestors.

Later, the Count asks Jonathan questions about conducting business in England, particularly about how he could go about shipping goods between Transylvania and Carfax. He tells Jonathan that he must stay at the castle for another month to help the Count take care of his business interests, and although Jonathan is terrified of the thought, he realizes he must comply. Not only is he a prisoner, but he still feels that he must follow through for the sake of his employer, Peter Hawkins. The Count tells Jonathan to write only of business in his letters home, making it clear that he is going to screen the letters. Jonathan decides to write on the provided paper for now, but to write full secret letters to his fiancée Mina and to his boss. To Mina, he will write in shorthand. He will try to find some way to send the letters secretly. At one point, when the Count leaves, Jonathan begins to snoop through the Count’s correspondence. Before he can discover anything, the Count returns and warns him never to fall asleep in any room other than his bedroom. That night, Jonathan looks out into the vast open space on the south side of the castle. When he looks down, Jonathan sees the Count crawling down the side of the castle, face down.

On a later night, he observes the Count leave the castle this way. He takes the opportunity to explore the place, pushing his way through a broken door. He discovers a large and previously unexplored wing of the castle, ruined and full of moth-eaten and dilapidated furniture. Not heeding the Count’s warning, he falls asleep. He has a dream which may not have been just a dream of three beautiful women who enter the room and talk of who will “kiss” him first. Jonathan is simultaneously full of fear and lust, and does not move but continues to watch the women through half-closed eyes. One of the women leans in and begins to bite at his neck, when the Count appears suddenly and forces the women back. Outraged, the Count tells the women that Harker belongs to him. He promises them that once he is through with Jonathan, the women can have him, and then he gives them a small bag that moves as if a child is inside of it. Horrified, Jonathan loses consciousness.

Analysis

Though Stoker wrote Dracula well after the heyday of the Gothic novel—the period from approximately 1760 to 1820—the novel draws on many conventions of the genre, especially in these opening chapters. Conceived primarily as bloodcurdling tales of horror, Gothic novels tend to feature strong supernatural elements juxtaposed with familiar backdrops: dark and stormy nights, ruined castles riddled with secret passages, and forces of unlikely good pitted against those of unimaginable evil. Stoker echoes these conventions, as the frantic superstitions of the Carpathian peasants, the cold and desolate mountain pass, and Harker’s disorienting and threatening ride to Dracula’s castle combine to create a mood of doom and dread.

As contemporary readers, we may find the setting vaguely reminiscent of Halloween, but Stoker’s descriptions, in fact, reveal a great deal about nineteenth-century British stereotypes of Eastern Europe. As Harker approaches Dracula’s castle, he notes that his trip has been “so strange and uncanny that a dreadful fear came upon [him].” Harker’s sense of dread illustrates his inability to comprehend the superstitions of the Carpathian peasants.

Indeed, as an Englishman who “visits the British Museum” in an attempt to understand the lands and customs of Transylvania, Harker emerges as a model of Victorian reason, a clear product of turn-of-the-century England. Harker’s education, as well as his Western sense of progress and propriety, disables him from making sense of such rustic traditions as “the evil eye.” To a man of Harker’s position and education, the strange sights he witnesses en route to the castle strike him as rare curiosities or dreams. He already begins doubting the reality of his experience: “I think I must have fallen asleep and kept dreaming. . . .” Harker’s inability to accept what is unknown, irrational, and unprovable is echoed by his English and American compatriots later in the novel. Harker’s experience suggests that the foundations of Western civilization—reason, scientific advancement, and economic domination—are threatened by the alternative knowledge that they presume to have surpassed. Western empirical knowledge is vulnerable because it has summarily dismissed foreign ways of thinking and, in doing so, has failed to recognize the power of such alternative modes of thought.

Harker’s description of his ascent to the castle as “uncanny” foreshadows the psychological horror of the novel. In 1919, Sigmund Freud published an essay called “The Uncanny,” in which he analyzed the implications of feelings and sensations that arouse “dread and horror.” Freud concludes that uncanny experiences can arise at two times. First, they can arise when primitive, supposedly disproved beliefs suddenly seem to be confirmed or validated once again. Second, the uncanny can arise when repressed infantile complexes are revived. Most academic criticism of Dracula relies heavily on such psychoanalytic theory and argues that the novel can be seen as a case study of repressed instincts coming to the surface. Indeed, such a reading seems inevitable if one considers Freud’s model of psychosexual development, which links the first stage of this development—the oral stage—with the death instinct, the urge to destroy what is living. The vampire, bringing about death with his mouth, serves as a fitting embodiment of these abstract psychological concepts, and allows Stoker to investigate Victorian sexuality and repression.

The Author’s Note with which Dracula begins reflects a popular conceit in the eighteenth-century fiction. Rather than constructing a narrative from the perspective of an omniscient third-person narrator, Stoker presents the story through transcribed journals. In effect, the novel masquerades as a real diary. Were the story told as a first-person reflection, we would be sure of the fate of the protagonist: because he is telling his tale, he must have lived through it. However, because the author of the diary writes directly as events happen, he may be tragically unaware of the danger of his surroundings. Harker has no time to reflect on his experiences and no way of knowing if he is placing himself in danger.

This real-time technique is popular within the horror genre: since the narrator has no way of knowing how the story will end, neither does the audience. The 1999 film The Blair Witch Project provides an excellent example of this conceit in recent popular culture. The film purports to be the exact contents of several film reels found in a supposedly haunted Maryland forest, shortly after a documentary film team vanished there while attempting to record supernatural activity. Watching the film, we experience what the documentary filmmakers supposedly experienced, in real time, to terrifying effect.

Because contemporary readers are so familiar with the vampire legend—whether in the form of The Lost Boys, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Salem’s Lot, or countless other incarnations—it is difficult to appreciate the magnitude of shock and dread that Stoker’s contemporaries felt upon reading his novel. For us, the suspense more likely comes from watching the characters piece together the count’s puzzle.

The novel contains one of the most discussed scenes. Drifting in and out of consciousness, Harker is visited by the three female vampires, who dance seductively before the angry count drives them away. The women’s appearance in the room where Harker is sleeping is undeniably sexual, as the Englishman’s characteristically staid language becomes suddenly ornate. Harker notes “the ruby of their voluptuous lips” and feels “a wicked, burning desire that they would kiss me.”

Harker is simultaneously confronting a vampire and another creature equally terrifying to Victorian England: an unabashedly sexual woman. The women’s voluptuousness puts them at odds with the two English heroines, Lucy Westenra and Mina Murray, whom we see later in the novel. The fact that the vampire women prey on a defenceless child perverts any notion of maternity, further distinguishing them from their Victorian counterparts. These “weird sisters,” as Van Helsing later calls them, stand as a reminder of what is perhaps Dracula’s greatest threat to society: the transformation of prim, proper, and essentially sexless English ladies into uncontrollable, lustful animals.

Harker spends a lot of time wondering whether this vision of repulsion and delight is real. He is unsure whether the women actually bend closer and closer to him, or if he merely dreams of their approach. If the women are real, they threaten to drink Harker’s blood, fortifying themselves by depleting his strength. If they are merely part of a fantastic dream , as Harker suspects, they nonetheless threaten to drain him of his vital energy. Critic C.F. Bentley believes that the passage which Harker lies “in -languorous ecstasy and wait[s]—wait[s] with beating heart” suggests something else. Either way, Harker stands to be drained of a vital fluid, which to the Victorian male imagination represents an overturning of the male-dominated social structure.