Chapter 5

From Dr. Seward’s diary; the September 22nd entry of Mina Harker’s journal; the September 22nd entry of Dr. Seward’s diary; and two articles from the Westminster Gazette, dated September 25th.

Lucy and Mrs. Westenra are to be buried together. Van Helsing takes possession of Lucy’s diary, and the two doctors deal with the logistics of the burial and the Westenras’ papers. Lucy’s body has been dressed and prepared by the undertaker and his staff, and if anything looks more beautiful than ever. Van Helsing seems disturbed by this phenomenon, and he puts garlic flowers around the bed and the body. He also puts a crucifix over Lucy’s mouth. He tells Seward that the next day they are going to decapitate her and stuff her mouth with garlic. But the next morning, Van Helsing reports to Seward that the crucifix was stolen (although he retrieved it) and consequently they will have to wait before doing anything. Seward cannot understand Van Helsing’s actions, but he trusts him. Arthur Holmwood (Lord Godalming now that his father is dead) is the beneficiary of the Westenras’ estate. When he arrives, heartbroken and in deep pain, Van Helsing and he affirm that they are friends. Van Helsing asks to read Lucy’s diary, and Arthur gives his permission.

Mina and Jonathan are in London when Jonathan sees the Count. Suddenly he seems to remember something he is horrified, saying that the Count is here and is now grown young, but he is so upset that he passes out and on waking can remember nothing. Disturbed by these bouts of forgetfulness, Mina resolves to open Jonathan’s diary and read it for his own sake. But that night, they arrive home to find a telegram informing them of the deaths of Lucy and Mrs. Westenra. Meanwhile, as Seward reports in what he believes will be his last diary entry, Lucy is buried and Van Helsing is going to Amsterdam for a brief visit.

Newspaper reports show that a number of children have temporarily gone missing in the same area where Lucy was buried. The children claim to have played with a “bloofer lady.” They return with small bite wounds on their necks.

Includes the September 23rd and September 24th entries of Mina Harker’s journal; a letter from Van Helsing to Mina Harker, dated September 24th; a telegram from Mrs. Harker to Van Helsing, dated September 25th; letters between Van Helsing and Mrs. Harker, dated September 25th; the September 26th entry of Jonathan Harker’s journal; and the September 26th entry of Dr. Seward’s diary.

Mina reads Jonathan’s journal, and is troubled by the contents. She believes that the writings in the journal may have been influenced by the brain fever, but she is not sure. She decides to transcribe it (it is in shorthand), so that it may be made intelligible to others if the need arises. Van Helsing, who has read Mina’s letters to Lucy, visits Mina to ask questions about the events leading up to Lucy’s death. Mina is impressed by the doctor, and she gives him Jonathan’s journal. Van Helsing reads it and comes to see the Harkers the next day. Jonathan’s spirits are restored by Van Helsing’s belief in him, and he is regaining his memories of the horrible events in Transylvania. Van Helsing praises Mina, her mind and her virtue, and he pledges friendship with Jonathan. He wants to ask questions to Jonathan about Transylvania at some point in the near future. As he is leaving by train, he sees the newspaper article on the “bloofer lady” and is horrified by how quickly the attacks have begun.

Dr. Seward has reopened his diary. He reports that Renfield is back to his old business of flies and spiders. He meets Van Helsing, who shows him the article about the wounded children and insinuates a connection between Lucy’s death and the recent attacks. Seward is sceptical. Van Helsing launches into a long speech about the many unexplained phenomena in the world, urging him to open his mind. Seward guesses that whatever thing caused Lucy’s death is now attacking children, which Van Helsing sadly denies. He tells Seward that the attacks were made by Lucy herself.

Includes the September 26th and September 27th entries of Seward’s diary; a note left by Van Helsing for Seward (not delivered), dated September 27th; and the September 28th and September 29th entries of Seward’s diary.

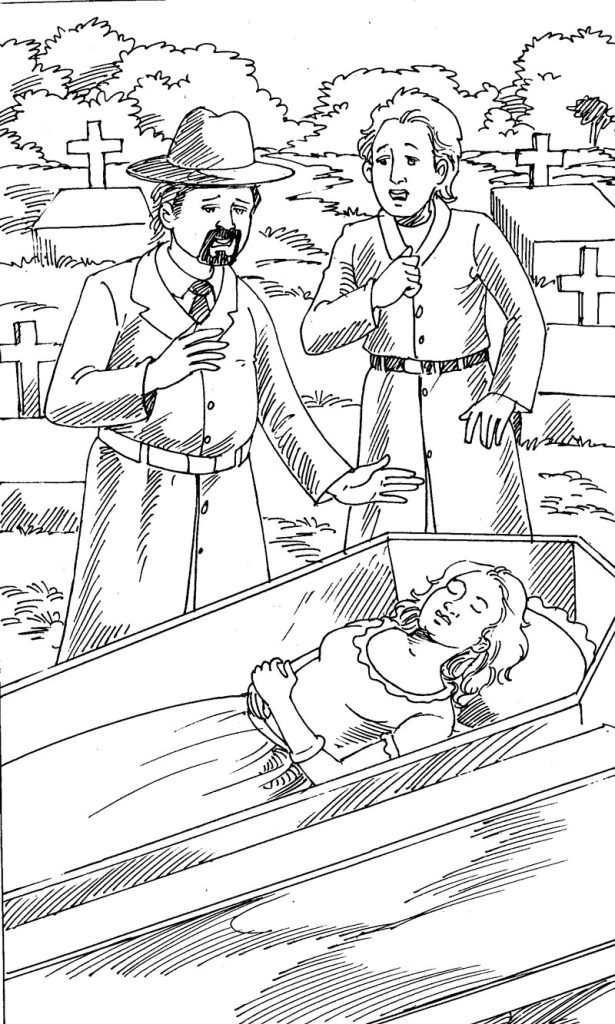

Seward is doubtful of Van Helsing’s theory, but he agrees to accompany him to examine one of the child victims. The wounds are nearly identical to the ones Lucy had, and the doctor tells them that the child asked, on waking, if he could go and “play with the bloofer lady.” That night, Seward and Van Helsing break into the Westenra family vault. Lucy’s coffin is empty, but Seward remains unconvinced. They wait outside. Just before daybreak, a white figure is seen moving across the graveyard. Van Helsing finds a small child. They leave the child on a pathway for a policeman to find; the two men wait in the bushes until they are sure the child is safe. The next day, they break into the vault and find Lucy’s body in the coffin. If anything, she looks more beautiful and radiant than ever. Van Helsing finally reveals to Seward, in explicit terms, that her death was caused by a vampire and she is now one of the undead. Although he wants to kill her now, he thinks it is best that Arthur learn of what has happened. He will use garlic and crucifix to keep Lucy in her tomb. After a night’s sleep, Seward begins to doubt Van Helsing again. That day, Van Helsing tells Quincey and Arthur that they most go to the Westenra vault and open Lucy’s tomb. He tells them that Lucy is now undead, and that he will have to decapitate her. Arthur is initially outraged, and refuses consent, but after an impassioned plea for trust from Van Helsing, he agrees to at least go to the tomb.

Analysis

In this section, we witness Lucy’s transformation into a super-natural creature. The description of her death immediately alerts us that she has crossed into the realm of the supernatural: the wounds on her neck disappear and all of her “loveliness [comes] back to her in death.” The clippings about the threatening “Bloofer Lady” make it clear that Lucy has indeed become a vampire. Dracula’s attack has transformed a model of English chastity and purity into an openly sexual predator. When Holmwood visits Lucy for the last time, her physical appeal startles him: “She looked her best, with all the soft lines matching the angelic beauty of her eyes.” Equally startling is the newfound forwardness with which she demands sexual satisfaction: “Arthur! Oh, my love, I am so glad you have come! Kiss me!” Dracula’s power has indeed topped one former example of the Victorian female ideal.

Lucy’s body also becomes a metaphorical battleground between the forces of good and evil, between the forces for liberation and repression of female sexuality. While Dracula fights for control of Lucy, through whom he believes he can access many Englishmen, Van Helsing’s crew pumps her full of brave men’s blood, which they believe is the “best thing on this earth when a woman is in trouble.” This battle reflects the struggle of Victorian society to recognize and accept female sexuality. Victorian England prized women for their docility and domesticity, leaving them no room for open expression of sexual desire, even within the confines of marriage. Mina, though married, appears no less chaste than Lucy. This obsession with purity was pervasive: less than twenty years before the publication of Dracula, medical authorities still believed that a bad woman could spoil meat simply by touching it. Van Helsing articulates these prejudices of the Victorian age as he praises Mina’s character, saying:

“She is one of God’s women, fashioned by His own hand to show us men and other women that there is a heaven where we can enter, and that its light can be here on earth. So true, so sweet, so noble, so little an egoist—and that, let me tell you, is much in this age, so sceptical and selfish.”

Van Helsing’s statement implies that a woman who cannot manage this much truth, sweetness, nobility and modesty has no place in Victorian society. Though Lucy possesses all of these in plenty, she also betrays a fatal flaw: her openness to sexual adventure. Recalling Van Helsing’s lesson in vampire lore, we know that Dracula is powerless to enter a home unless invited. The count thus would not have been able to access Lucy’s bedroom unless she invited him in. Though no character ever blames Lucy for her susceptibility to seduction—or even mentions it—we are aware that the young woman has fallen from grace. Victorian society firmly dictated that wantonness came at a high price, and in Dracula, Lucy pays dearly.