Chapter 23

Emma’s pensive meditations, as she walked home, were not interrupted; but on entering the parlour, she found those who must rouse her. Mr. Knightley and Harriet had arrived during her absence, and were sitting with her father. Mr. Knightley immediately got up, and in a manner decidedly graver than usual, said, “I would not go away without seeing you, but I have no time to spare, and therefore must now be gone directly. I am going to London, to spend a few days with John and Isabella. Have you any thing to send or say, besides the `love,’ which nobody carries?”

“Nothing at all. But is not this a sudden scheme?”

“Yes—rather—I have been thinking of it some little time.”

Emma was sure he had not forgiven her; he looked unlike himself. Time, however, she thought, would tell him that they ought to be friends again. While he stood, as if meaning to go, but not going. Her father began his inquiries.

“Well, my dear, and did you get there safely? And how did you find my worthy old friend and her daughter? I dare say they must have been very much obliged to you for coming. Dear Emma has been to call on Mrs. and Miss Bates, Mr. Knightley, as I told you before. She is always so attentive to them!”

Emma’s colour was heightened by this unjust praise; and with a smile, and shake of the head, which spoke much,

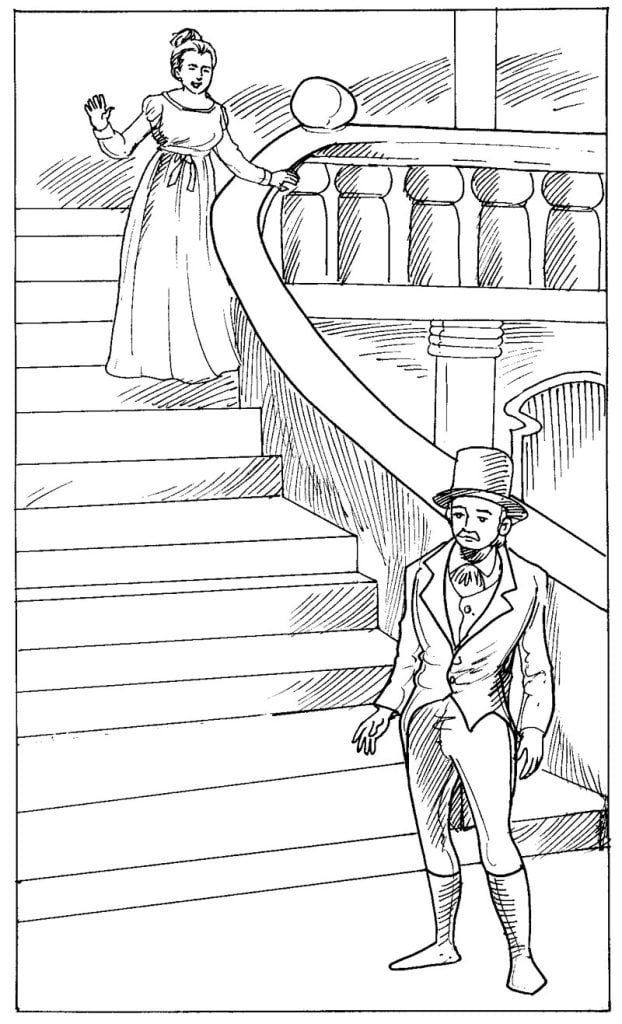

she looked at Mr. Knightley. It seemed as if there were an instantaneous impression in her favour, as if his eyes received the truth from her’s, and all that had passed of good in her feelings were at once caught and honoured. He looked at her with a glow of regard. She was warmly gratified and in another moment still more so, by a little movement of more than common friendliness on his part. He took her hand; whether she had not herself made the first motion, she could not say. She might, perhaps, have rather offered it—but he took her hand, pressed it, and certainly was on the point of carrying it to his lips when, from some fancy or other, he suddenly let it go. Why he should feel such a scruple, why he should change his mind when it was all but done, she could not perceive. He would have judged better, she thought, if he had not stopped. The intention, however, was indubitable; and whether it was that his manners had in general so little gallantry, or however else it happened, but she thought nothing became him more. It was with him, of so simple, yet so dignified a nature. She could not but recall the attempt with great satisfaction. It spoke such perfect amity. He left them immediately afterwards gone in a moment. He always moved with the alertness of a mind which could neither be undecided nor dilatory, but now he seemed more sudden than usual in his disappearance.

One morning, about ten days after Mrs. Churchill’s decease, Emma was called downstairs to Mr. Weston, who could not stay five minutes, and wanted particularly to speak with her.” He met her at the parlour-door, and hardly asking her how she did, in the natural key of his voice, sunk it immediately, to say, unheard by her father, “Can you come to Randalls at any time this morning? Do, if it be possible. Mrs. Weston wants to see you. She must see you.”

“Is she unwell?”

“No, no, not at all—only a little agitated. She would have ordered the carriage, and come to you, but she must see you alone, and that you know (nodding towards her father) Humph! Can you come?”

“Certainly. This moment, if you please. It is impossible to refuse what you ask in such a way. But what can be the matter? Is she really not ill?”

“Depend upon me but ask no more questions. You will know it all in time. The most unaccountable business! But hush, hush!”

To guess what all this meant, was impossible even for Emma. Something really important seemed announced by his looks; but, as her friend was well, she endeavoured not to be uneasy, and settling it with her father, that she would take her walk now, she and Mr. Weston were soon out of the house together and on their way at a quick pace for Randalls.

“Now,” said Emma, when they were fairly beyond the sweep gates, “now Mr. Weston, do let me know what has happened.”

“No, no,” he gravely replied, “Don’t ask me. I promised my wife to leave it all to her. She will break it to you better than I can. Do not be impatient, Emma; it will all come out too soon.”

“Break it to me,” cried Emma, standing still with terror. “Good God! Mr. Weston, tell me at once. Something has happened in Brunswick Square. I know it has. Tell me, I charge you tell me this moment what it is.”

“No, indeed you are mistaken.”

“Mr. Weston do not trifle with me. Consider how many of my dearest friends are now in Brunswick Square. Which of them is it? I charge you by all that is sacred, not to attempt concealment.”

“Upon my word, Emma.”

“Your word! why not your honour! why not say upon your honour, that it has nothing to do with any of them? Good Heavens! What can be to be broke to me, that does not relate to one of that family?”

“Upon my honour,” said he very seriously, “it does not. It is not in the smallest degree connected with any human being of the name of Knightley.”

Emma’s courage returned, and she walked on.