Famously known as the “first American spy,” Hale was a soldier for the continental Army during the American Revolutionary War in 1775. He was officially designated the state hero of Connecticut after he had volunteered to go behind enemy lines and observe the movements of the British during the Battle of Long Island. Disguised as a Dutch teacher on his way to New York, he was eventually caught by the British and hanged.

Nathan Hale (June 6, 1755—September 22, 1776) was a soldier for the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He volunteered for an intelligence-gathering mission in New York City but was captured by the British and executed. He is probably best remembered for his purported last words before being hanged, “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.” Hale has long been considered an American hero and, in 1985, he was officially designated the state hero of Connecticut.

Background

Nathan Hale was born in Coventry, Connecticut, in 1755 to Richard Hale and Elizabeth Strong. In 1768, when he was fourteen years old, he was sent with his brother Enoch, who was sixteen, to Yale College. Nathan was a classmate of fellow patriot spy Benjamin Tallmadge. The Hale brothers belonged to the Yale literary fraternity, Linonia, which debated topics in astronomy, mathematics, literature and the ethics of slavery. Graduating with first-class honours in 1773 at 18, Nathan became a teacher, first in East Haddam and later in New London.

After the Revolutionary War had begun in 1775, he joined a Connecticut militia and was elected first lieutenant. When his militia unit participated in the Siege of Boston, Hale remained behind. It has been suggested that he was unsure as to whether he wanted to fight—or perhaps it was because his teaching contract in New London did not expire until several months later, in July 1775. On July 4, 1775, Hale received a letter from his classmate and friend, Benjamin Tallmadge. Tallmadge, who had gone to Boston to see the siege for himself, wrote to Hale, “Were I in your condition, I think the more extensive service would be my choice. Our holy Religion, the honour of our God, a glorious country and a happy constitution is what we have to defend.” Tallmadge’s letter was so inspiring that several days later, Hale accepted a commission as first lieutenant in the 7th Connecticut Regiment under Colonel Charles Webb of Stamford. In the following spring, the army moved to Manhattan Island to prevent the British from taking over New York City. In September, General Washington was desperate to determine the upcoming location of the British invasion of Manhattan Island. Washington sought to do this by sending a spy behind enemy lines, and Hale was the only volunteer. Still having not physically fought in war yet, Hale saw this as a crucial opportunity to fight for the patriotic cause.

Intelligence-gathering mission

During the Battle of Long Island, which led to British victory and the capture of New York City via a flanking move from Staten Island across Long Island, Hale volunteered on 8th September, 1776, to go behind enemy lines and report on British troop movements. He was ferried across on September 12. It was an act of spying that was immediately punishable by death and posed a great risk to Hale.

During his mission, New York City (then the area at the southern tip of Manhattan around Wall Street) fell to British forces on September 15 and Washington was forced to retreat to the island’s north in Harlem Heights (what is now Morningside Heights). On September 21, a quarter of the lower portion of Manhattan burned in the Great New York Fire of 1776. The fire was later widely thought to have been started by American saboteurs to keep the city from falling into British hands, though Washington and the Congress had already denied this idea. It has also been speculated that the fire was the work of British soldiers acting without orders. In the aftermath of fire, more than 200 American partisans were rounded up by the British.

An account of Nathan Hale’s capture was written by Consider Tiffany, a Connecticut shopkeeper and Loyalist, and obtained by the Library of Congress. In Tiffany’s account, Major Robert Rogers of the Queen’s Rangers saw Hale in a tavern and recognized him despite his disguise. After luring Hale into betraying himself by pretending to be a patriot himself, Rogers and his Rangers apprehended Hale near Flushing Bay in Queens, New York. Another story was that his Loyalist cousin, Samuel Hale, was the one who revealed his true identity.

British General William Howe had established his headquarters in the Beekman House in a rural part of Manhattan, on a rise between the 50th and 51st Streets between the First and Second Avenues, near where Beekman Place commemorates the connection. Hale reportedly was questioned by Howe, and physical evidence was found on him. Rogers provided information about the case. According to tradition, Hale spent the night in a greenhouse at the mansion. He requested a Bible; his request was denied. Sometime later, he requested a clergyman. Again, the request was denied.

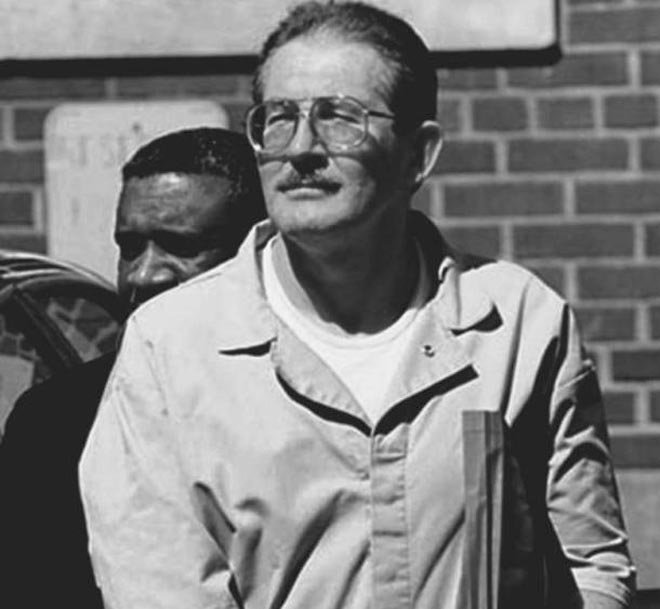

According to the standards of the time, spies were hanged as illegal combatants. On the morning of 22nd September, 1776, Hale was marched along Post Road to the Park of Artillery, which was next to a public house called the Dove Tavern (at modern day 66th Street and Third Avenue), and hanged. He was 21 years old. Bill Richmond, a 13-year-old former slave and Loyalist who later became famous as an African American boxer in Europe, was reportedly one of the hangmen. His responsibility was that of fastening the rope to a strong tree branch and securing the knot and noose.

Nathan Hale’s scholar Mary Beth Baker has argued that some of Hale’s posthumous fame arose from a desire by alumni of Yale to claim a Revolutionary War hero, in addition to Yale president Naphtali Daggett, John Trumbull and others.

Hanging sites

Besides the site at the 66th Street and the Third Avenue, currently a Gap store, two other sites in Manhattan claim to be the hanging site:

“City Hall Park, where a statue designed by Frederick William Macmonnies was erected in 1890 “Inside Grand Central Terminal

” The Yale Club at the 44th Street and Vanderbilt Avenue, near Grand Central Terminal, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) hung a plaque which states the event occurred there.

Nathan Hale’s body has never been found. His family erected an empty grave cenotaph in Nathan Hale Cemetery in South Coventry, Connecticut.

Famous relatives

Hale was the great-grandson of John Hale, an important figure in the Salem Witch Trials of 1692. Nathan Hale was also the uncle of orator and statesman Edward Everett (the other speaker at Gettysburg) and the grand-uncle of Edward Everett Hale (quoted above), a Unitarian minister, writer and activist noted for social causes including abolitionism. He was the uncle of Nathan Hale who founded the Boston Daily Advertiser, and helped establish the North American Review.