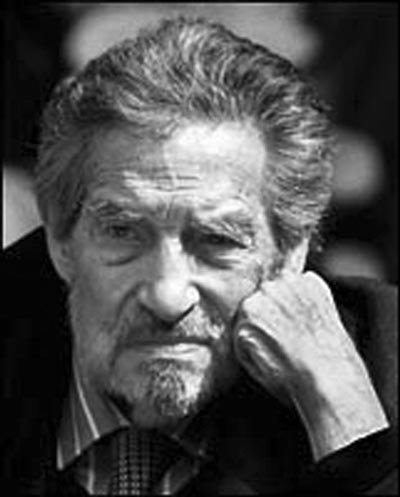

Mexican poet, writer, and diplomat, who received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1990. With Pablo Neruda and Cesar Vallejo, Paz is one of the several Latin American poets whose work has had wide international impact. Although many of Paz’s poems are developed within the discipline of regular meter and rhyme, he has also experimented with the form. Among his most famous poems is Piedra De Sol (1957, Sun Stone), referring to the planet Venus, a symbol of sun and water in Aztec folklore; Goddess of love in Western mythology. The poems were modelled on the famous Aztec calendar stone. It starts with the same lines with which it ends, and unites in the first part nature and love.

Octavio Paz was born in Mexico City. His grandfather was a novelist and his father worked as a secretary to Emiliano Zapata. When Zapata was driven into retreat and assassinated, the family lived in exile in the United States for a short time. After the return to Mexico, Paz studied law and literature at the National University, but refused to take his degree. However, from his youth Paz’s ambition was to be a poet. Encouraged by Pablo Neruda, Paz started to write. From 1933 he published over 40 books. Paz’s first collection was Luna Silvestre (1933).

In 1937 Paz married Elena Garro; they divorced in 1959. During the Spanish Civil War, Paz visited Spain, and fought on the Republican side. His experiences in Spain, where he met among others Andre Malraux, Andre Gide, and Ilja Ehrenburg, Paz recorded in the collection Bajo Tu Clara Sombra Y Otros Poemas (1937). The leftist overtones of his poetry were temporary, but he remained unyielding in his defence of freedom of expression and democracy. From the 1940s he started to use Surrealistic images.

In the late 1930s and in the 1940s Paz worked as a journalist. He founded and edited several important literary reviews, including Taller (1938-41) and El hijo prodigo. At the beginning of the 1940s, Paz received a Guggenheim fellowship for travel and studies at the University of Berkley. After WW II he joined the Mexican Diplomatic Corps. He spent six years in Paris. “My superiors had forgotten me, and I secretly thanked them,” he later wrote in Vislumbres De La India (1995). He was devastated to leave his friends and the city, but continued his career in Japan, the United States, and India, serving also as Mexico’s representative to UNESCO. In 1968 Paz resigned his diplomatic post in protest over the massacre of students at Plaza Tlateloco in Mexico City in October, before the Olympic Games. Paz moved back to Mexico in 1969 and started in his poetry to explore his childhood and youth. In Vuelta (1976) and Pasado En Claro (1975) he used autobiographical material. In ‘San Ildefonso Nocturne’ Paz looked ironically into the past and asked what has happened to those who wanted to “set the world right.”

From 1968 to 1970 Paz was a visiting professor of Spanish American Literature at the universities of Texas, Austin, Pittsburgh and Pennsylvania. From 1971-76 Paz was editor of the Plural, and from 1976 he edited the Vuelta. In 1982 he won the prestigious Neustadt Prize. Paz’s collected poems (1957-87), in Spanish and English, were published in 1988.

Paz had early adopted influences from Marxism, surrealism, existentialism, Buddhism, Hinduism, French and Anglo-American modernism. However, by the time of the Nobel prize, he had become a conservative; he also defended the contra wars in Nicaragua.

As an essayist Paz dealt with such issues as Aztec art, Tantric Buddhism, Mexican politics, neo-platonic philosophy, economic reform, avant-garde poetry, structuralist anthropology, utopian socialism, the dissident movement in the Soviet Union, sexuality and eroticism. El Laberinto De La Soledad (1950, The Labyrinth of Solitude) is considered one of the most influential studies of life, Mexican character and thought.

Los Hijos Del Limo (1974) explores the history of modern poetry from German Romanticism to the 1960s avant-garde. Paz’s distaste for the materialism of the Western democracies is seen in Corriente Alterna (1967). Posdata (1970) was an interpretation of the failures of Mexico’s political system and its relation to culture. Although Paz was known as a supporter of the neo-liberal economic policies, he criticized the weakness of liberal democracy in Tiempo Nublado (1983), La Otra Voz (1990) and Itinerario (1993). Paz’s numerous essays on Hispanic and French poetry include El Arco Y La Lira (The Bow and the Lyre 1956), Los Hijos Del Limo (Children of the Mire 1974), and Marcel Duchamp (1968). In Essays on Mexican Art (1993) Paz dealt with pre-Columbian art, its ‘otherness’ manifested in massive blocks of carved stone. He also contemplated on the secret of Rufino Tamayo’s paintings, and examined critically Frieda Kahlo’s self-portraits. “The true artist is the one who says no even when he says yes,” Paz once wrote.

Octavio Paz died at the age of 84 on April 19, 1998.