Chapter 1

My adventures began early one June morning in the year 1751. I was a lad of seventeen. I locked the door of my father’s house for the last time. The sun shone on the hilltops as I went down the road.

Mr. Campbell, the minister, was waiting for me by his garden gate.

“Well, David,” said he, “I will go with you to the river, to start you on your way.”

We bagan to walk in silence.

“Are you sorry to leave Essendean?” he asked.

“Essendean is a good place,” said I, “but I have never been anywhere else.”

“Well, David,” said Mr. Campbell, “when your mother had gone and your father was dying, he gave me this letter and told me to give you the letter and send you to the house of Shaws, where he came from.”

“The house of Shaws!” I cried, “What had my poor father to do with the house of Shaws?”

“Who can tell?” said Mr. Campbell, “The name of that family, David, is your name—Balfour of Shaws.”

The letter was addressed: “To the hands of Ebenezer Balfour, of Shaws, these will be delivered by my son, David Balfour.” My heart was beating hard.

“Mr. Campbell,” I stammered, “if you were in my shoes, would you go?”

“Oh yes, I would,” said the minister.

He gave me a little packet, then embraced me very hard, looking like he was about to cry. He turned away quickly, crying goodbye, and set off at a jogging run. I watched him as long as I could. He never stopped hurrying, nor once looked back.

He had given me a small Bible, a shilling and a recipe for Lily of the Valley water. That recipe was to help me wonderfully in health and sickness all my life.

I was sad to leave my good friend, but glad to set out on my way. When I came to the green road up the side of the hill, I took my last look at the Essendean Church and the trees in the yard where my father and mother lay buried.

On the afternoon of the second day, I saw all the countryside before me fall away down to the sea. There were ships in the inlet and a flag upon the castle at Edinburgh. It was my first view of the sea, and I stood in wonder for some time.

I began to ask directions to the house of Shaws. The folk I asked looked at me strangely. One honest fellow told me that Shaws was a big house with only Mr. Ebenezer in it. “And mannie,” he added, “it’s none of my affairs, but you seem a decent spoken lad. If you take my word, you’ll keep clear of the Shaws.”

What sort of house, or man, could make the country folk so uneasy? If I had been closer to Essendean, I would have turned back.

Near sundown, I reached the house of Shaws. This was no great house. It appeared to be in ruin. No road led up to it. No smoke rose from any of the chimneys. My heart sank.

I walked through the grass past two stone pillars, a main entrance gate that had never finished. One wing of the house had no roof, and steps and stairs showed against the sky. Some of the windows had no glass, and bats flew in and out.

I lifted my hand with a faint heart and knocked once on the door. Then I stood and waited. No one answered.

I began to shout aloud for Mr. Balfour. Then I heard a cough right overhead. I jumped back and looking up, saw a man’s head in a tall nightcap and the wide mouth of a blunderbuss at a window.

“It’s loaded,” said a voice.

“I have come with a letter,” I said, “to Mr. Balfour of Shaws. Is he here?”

“Who are you yourself?”

“They call me David Balfour,” said I.

I heard the blunderbuss rattle on the windowsill. After a long pause with a curious change of voice, he asked, “Is your father dead?”

I was so surprised I could not answer, but stood staring.

“He must be dead; that’s what brings you knocking at my door. Well, man,” he said, “I’Il let you in.” Soon there came a great rattling of chains and bolts. The door was opened slowly and shut again behind me.

“Go into the kitchen and touch nothing,” said the voice.

I came to the barest room I ever laid eyes on. There was nothing in the great stone chamber but a table set for a poor supper, a few dishes on a shelf, and locked chests along the wall.

The man joined me. He was a mean, stopping, clay-faced creature, and his age was anything between fifty and seventy. He wore a flannel nightcap and nightgown, and he was unshaved.

“Let’s see the letter,” said he.

I told him the letter was for Mr. Balfour, the lord of Shaws.

“Hoot-toot! And who do you think I am?” he said, “Give me Alexander’s letter!”

“You know my father’s name?”

“It would be strange if I didn’t,” he said.

“He was my brother. I’m your uncle, David my boy; Give me the letter, and sit down and eat.”

There was only one bite of porridge left. This was no rich house, and my uncle was no great lord. I was so disappointed I almost cried.

“Your father’s been long dead,” he said.

“There weeks, sir,” said I, “I never knew he had a brother till you told me.”

He lit no lamp on the steps as he showed me my bed. I stumbled after him in the dark.

“Lights in a house are a thing I do not like. Good night to you.” He pulled the door shut and locked me in.

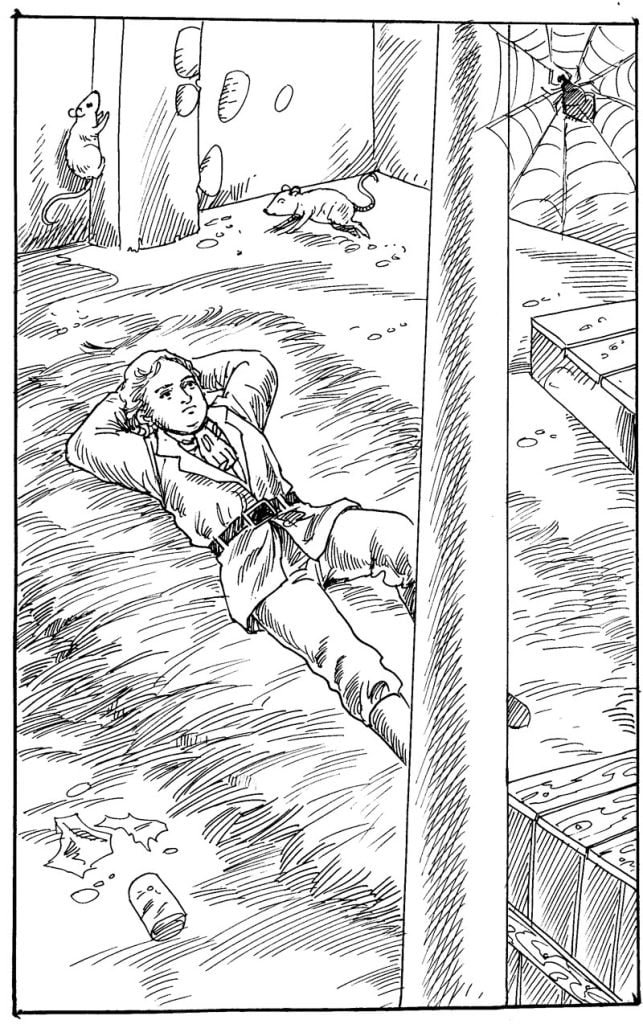

The room was cold as a well and the bed was damp. I rolled myself in my plaid and slept on the floor.

When I woke, I was cold and miserable. I could see that only spiders and mice used the room now. I knocked and shouted till my jailer came and let me out.

At breakfast, he asked me about my mother and said she had been a bonnie lassie. I was surprised to hear that he knew her as well.

My uncle kept a close eye on me. I was sure he