1640-1755

The dynastic union holding together Spain and Portugal since 1580 was dissolved in 1640, and Portuguese independence restored (formally recognized by Spain only in 1668). The Portuguese Colonial Empire had remained an entity separate from the Spanish Colonial Empire, and remained Portuguese.

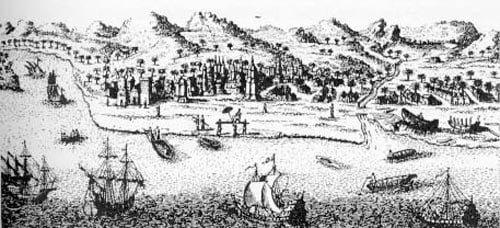

In 1661 English King Charles II. married Portuguese princess Catherine de Braganca. The colonies of Bombay (hitherto part of Portuguese India) and of Tanger (also called Tangiers, Morocco) made up part of her dowry; Bombay was the first foothold the East India Company, founded in 1600, but hitherto insignificant, acquired in India.

Goa suffered blockades from the Dutch in 1638-1644 and 1656-1663; while Goa withstood the pressure (in itself an accomplishment, as Portugal did do little to assist the Goanese, her resources were mainly used to fight the Dutch in Brazil), the Dutch took Malacca in 1641 and established their dominance in the Indonesian archipelago, reducing Portugal’s share in the spice trade to a minimum. The Dutch also expelled the Portuguese from Ceylon in 1659; the Portuguese possessions in India proper, after the loss of Malabar (the Portuguese garrison of Cochin surrendered to the Dutch in 1663) and the cession of Bombay, were reduced to Goa, Diu, Daman, Bassein and Chaul, and a number of outposts in Bengal.

The defence of Goa against the Dutch had been costly, both in fatalities and in expenses, while the profits from the India (Asia) trade had fallen rapidly. The Portuguese Empire in India entered a long period of economic decline, a phenomenon to which an administration discriminating against the Hindu population, and granting ethnic Portuguese privileged treatment, an administration following traditional patterns of an economic policy contributed. This at a time when the East India Company developed Bombay—obtained from the Portuguese—into a quickly growing trading hub.

Bassein, the most fertile of the Portuguese possessions in India, was lost to Maratha forces in 1739, Chaul surrendered to the Marathas in 1740. Sao Tome de Meliapore, the most important of Portugal’s outposts in Bengal, fell to the Qutbshashi of Golconda in 1662. In 1687 the Portuguese administration was restored; in a treaty with Bengal, in 1697 the fortifications were razed; British occupation in 1749 ended the Portuguese presence.

1755-1789

In 1756, the Marquis of Pombal was appointed chief minister of Portugal; until his demise in 1777 he virtually ruled the Portuguese Empire, an energetic reformer ruling with a strong hand, a believer in enlightenment. He suppressed the Jesuit Order in the Portuguese Empire in 1759 and ordered her property to be confiscated; he abolished slavery in 1773, the Inquisition in 1774. The suppression of the Jesuits (they had been expelled from the Portuguese Empire in 1751) was a major event, as the Jesuit Order owned land and buildings, ran granaries, on repeated occasions granted loans to the Goan administration, at interest. Not only were the monks arrested, later expelled; the Jesuit assets were disposed of. The Viceroy of Portuguese India was instructed to primarily hire natives in state administration, the armed forces and as clergymen. The attempt to break up the feudal class society, however, was limited to the christian population of Portuguese India; Hindus remained excluded.

After the demise of the Marquis de Pombal, the Inquisition was reinstated in 1778. In 1772 / 1778 the government employed teachers for the College of Natives (the former Jesuit college of St. Paul), the colony’s major institution of higher learning.

The reforms, as far as they reduced the power of the Catholic church, reduced Portuguese influence in the colony. With the administration no longer a monopoly of the ethnic Portuguese, their number declined, as did the population figure of Portuguese India in general.

The economy of Portuguese India was underdeveloped and stagnant. Goa, the capital of the Portuguese colonial Empire in Asia (which included Macau and Portuguese Timor), was in decay, her fortifications in a poor condition, the city abandoned in 1760. The territory of Goa was expanded in 1763 and 1788, by the annexation of a few districts.

There were insurrections in reaction to the Portuguese introduction of a tax on tobacco; in 1787 Goanese priests revolted against the practice of only peninsulares being appointed to top ecclesiastic positions.

1789-1815

Portuguese India in 1799 was occupied by East India Company forces, to prevent the French from using the ports of Portuguese India, especially Goa. In 1808 the British launched an inquiry into the Inquisition; the latter was abolished in 1812. The British occupation lasted until 1815. A plan suggested by Lord Wellesley, according to which the British and Portuguese would exchange Portuguese India for Malacca (which the British had taken from the Dutch, but did not own until 1824) was not executed.

1815-1878

In 1813 the British occupation of Goa ended and Portuguese rule resumed. Portugal being a British ally since 1661, her possessions in India were secure. The old capital of Goa suffered from an unhealthy environment; in 1827-1835 a new capital was constructed at Panjim, which officially was proclaimed capital in 1843. Construction costs, which were consideravle, were financed by revenues gained from Portuguese Indian merchants’ share in the Indian Ocean slave trade (Portugal formally banned slave trade in 1836, a decree not enforced) and in the Opium trade to China. Except for the teak felled in Dadra and Nagar Haveli, the economy of Portuguese India was described as moribund. Known ore deposits (iron) were mined, but poorly managed due to lack of investment and poor technology. Portuguese India experienced emigration; the Catholics among her population were partially westernized which helped them finding employment and obtain education in British India, where the city of Bombay exercised most attraction.

A government printing press was introduced in 1821, a private printing press in 1859. The issuance of postage stamps for Portuguese India began in 1871. In 1835 religious orders were suppressed. A Normal School (to train teachers) was established in 1841; every village was given a primary school. The first girls’ school was opened in 1846.

Ending a centuries-long policy of religious intolerance, in 1833 Hindus were permitted to practice their rites and ceremonies. The policy of discrimination against Hindus, however, continued until 1910. The administration of state and church continued to insist on the use of Portuguese as the only official language (instead of Konkani, the vernacular of Goa).

A British offer to purchase Portuguese India in 1839 was rejected.

The Ranes revolted against taxation in 1822, 1823, 1824 and 1845-1851.

1878-1918

In 1878, the port of Goa had been opened for trade with British India; in 1881 it was connected by railroad to the Indian railroad network.

In 1881, Goa had 445,449 inhabitants; Daman in 1870 had 40,980 inhabitants, Diu in 1877 had 13,898 inhabitants. Occasional revolts in the countryside (1882, 1895, 1912) were suppressed. In 1895, Portuguese Indian soldiers to be transferred to Mozambique.

In 1900 the first newspaper of Goa was founded; the population of Portuguese India was given as 475,513.

In 1910 Portugal became a republic. In Portuguese India, equality in front of the law was introduced—the Hindu segment of the population (49 %) formally was emancipated. Hindus now were granted access to schools (there was one high school in all of Portuguese India), qualified for positions in the administration.

In 1910, the Goa Exposition was held.

In the first half of World War I Portugal remained neutral (without formally declaring neutrality); then, in 1916, Germany declared war; Portugal thus joined the Entente. The war had limited impact on Portuguese India.

1939-1961

The political dictatorship in Portugal and the infringement on civil liberties in motherland and colonies continued. During much of World War II, Portugal was neutral. The war had limited impact on the colony. 4 ships sailing under Axis flags were set afire in the port of Goa in 1941, probably by British agents. The Portuguese authorities held the surviving sailors from these ships responsible.

In 1946, Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia launched a civil disobedience movement. In 1947, Portuguese India was proclaimed a Portuguese Overseas Province; St. Joao de Brito, a 17th century Jesuit missionary to India, was canonized. The right to elect their representatives in Portugal’s parliament had been restored to the colonies in 1945.

British India gained her independence in 1947. Yet while Portugal stubbornly held on to her colonies (in 1951 rechristened Overseas Provinces), even after France ceded her possessions in India in 1954, many Catholic Goans looked sceptically at the prospect of unification with India.The exclave of Dadra and Nagar Haveli was occupied by Indian forces in 1954. In 1954, Goa was formally granted autonomy—an autonomy criticized by the Goa National Union because it did not guarantee freedom of speech, assembly and the press. Portuguese-Indian relations deteriorated; postal connections were cut, the Portuguese legation in New Delhi closed in 1955. In the face of continued agitation by the Goa National Union in Portuguese India, martial law was declared (1955). The same year, an election was held in which the vast majority of the population was not allowed to vote. India imposed an economic blockade of Goa.

In 1950, Goa had a population of 547,000, with another 180,000 Goans living abroad. With Goa’s economy being backward and comparatively stagnant, many Goans tried to make a living abroad. The only high school in Goa used Portuguese as the language of instruction; private institutions offered English language education. Goa, Daman and Diu lacked a hinterland. One economic branch which developed after WW II was Goa’s mining industry (manganese, iron ore); the ore was exported to Japan, Goa failed to develop a metallurgical industry. In 1959, a currency reform was conducted; the Rupia was replaced by the Escudo.

The Indian independence movement had found few supporters among the population of Goa, Diu and Daman, a considerable percentage of which was Roman Catholic.

In 1961, Indian forces occupied the Portuguese possessions in India. In 1962 they were formally annexed by India; they formed the state of Goa, Daman and Diu. Portugal did not recognize India’s sovereignty over these territories until 1974.

Although the Indian government undertook a number of steps to modernize the economy of Goa, Diu and Daman, with considerable success, the inhabitants of Portuguese India rejected the integration of their territories in the surrounding Indian states.