Chapter 9

I was so dead asleep at first, being fatigued with rowing, or paddling, as it is called, the first part of the day, and with walking the latter part, that I did not wake thoroughly; but dozing between sleeping and waking, thought I dreamed that somebody spoke to me. But as the voice continued to repeat, “Robin Crusoe, Robin Crusoe,” at last I began to wake more perfectly, and was at first dreadfully frightened, and started up in the utmost consternation. But no sooner were my eyes open, than I saw my Poll sitting on the top of the hedge, and immediately knew that it was he that spoke to me; for just in such bemoaning language I had used to talk to him, and teach him; and he had learnt it so perfectly, that he would sit upon my finger, and lay his bill close to my face, and cry, “Poor Robin Crusoe, where are you? Where have you been? How have you come here?” and such things as I had taught him.

However, even though I knew it was the parrot, and that indeed it could be nobody else, it was a good while before I could compose myself: first I was amazed how the creature got thither, and then how he should just keep about the place, and nowhere else. But as I was well satisfied it could be nobody but honest Poll, I got it over; and holding out my hand, and calling him by his name Poll, the sociable creature came to me, and sat upon my thumb, as he used to do, and continued talking to me, “Poor Robin Crusoe,” and “How did I come here?” and “Where had I been?” just as if he had been over—joyed to see me again; and so I carried him home along with me.

I had now had enough of rambling to sea for some time, and had enough to do for many days to sit still and reflect upon the danger I had been in. In this government of my temper I remained near a year—lived a very sedate, retired life, as you may well suppose; and my thoughts being very much composed as to my condition, and fully comforted in resigning myself to the dispositions of Providence, I thought I lived really very happily in all things, except that of society.

I improved myself in this time in all the mechanic exercises which my necessities put me upon applying myself to, and I believed could, upon occasion, make a very good carpenter, especially considering how few tools I had.

Besides this, I arrived at an unexpected perfection in my earthenware, and contrived well enough to make them with a wheel, which I found infinitely easier and better; because I made things round and shapeable, which before were filthy things indeed to look at. But I thought I was never more vain in my own performance, or more joyful for anything I found out, than for my being able to make a tobacco-pipe. And although it was a very ugly clumsy thing when it was done, and only burned red like other earthenware, yet, as it was hard and firm, and would draw the smoke, I was exceedingly comforted with it; for I had been always used to smoke, and there were pipes on the ship, but I forgot them at first, not knowing that there was tobacco in the island; and afterwards, when I searched the ship again, I could not come at any pipes at all.

In my wicker ware, also, I improved much, and made abundance of necessary baskets, as well as my invention showed me. Though not very handsome, yet they were such as were very handy and convenient for my laying things up in, or fetching things home in. For example, if I killed a goat abroad, I could bang it up in a tree, flay it, dress it cut it in pieces and bring it home in a basket; and the like by a turtle—I could cut it up, take out the eggs, and a piece or two of the flesh, which was enough for me, and bring them home in a basket, and leave the rest behind me. Also large deep baskets were my receivers for my corn, which I always rubbed out as soon as it was dry, and cured, and kept it in great baskets.

I began now to perceive my powder abated considerably and this was a want which it was impossible for me to supply, and I began seriously to consider what I must do when I should have no more powder; that is to say, how I should do to kill any goat. I had, as is observed, in the third year of my being here, kept a young kid, and bred her up tame, and I was in hope of getting a he goat, but I could not by any means bring it to pass, till my kid grew an old goat; and I could never find in my heart to kill her till she died at last of mere age.

But being now in the eleventh year of my residence, and, as I have said, my ammunition growing low, I set myself to study some art to trap and snare the goats, to see whether I could not catch some of them alive, and particularly I wanted a she-goat great with young.

To this purpose I made snares to hamper them; and I do believe they were more than once taken in them; but my tackle was not good, for I had no wire, and I always found them broken, and my bait devoured.

At length I resolved to try a pit-fall. So I dug several large pits in the earth, in places where I had observed the goats used to feed; and over these pits I placed hurdles of my own making too, with a great weight upon them. And several times I put ears of barley, and dry rice, without setting the trap; and I could easily perceive that the goats had gone in and eaten up the corn, for I could see the marks of their feet. At length I set three traps in one night; and going the next morning, I found them all standing, and yet the bait eaten and gone. This was very discouraging. However, I altered my trap; and not to trouble you with particulars, going one morning to see my trap, I found in one of them a large old he-goat; and in one of the other, three kids—a male and two females.

As to the old one, I knew not what to do with him; he was so fierce I dared not go into the pit to him—that is to say, to go about to bring him away alive, which was what I wanted. I could have killed him; but that was not my business, nor would it answer my end. So I even let him out, and he ran away as if he had been frightened out of his wits. But I had forgotten then what I learnt afterwards—that hunger would tame a lion. If I had let him stay there three or four days without food, and then have carried him some water to drink, and then a little corn, he would have been as tame as one of the kids—for they are mighty sagacious, tractable creatures where they are well used.

However, for the present I let him go, knowing no better at that time. Then I went to the three kids; and taking them one by one, I tied them with strings together, and with some difficulty brought them all home.

It was a good while before they would feed; but throwing them the same sweet corn, it tempted them, and they began to be tame. And now I found that if I expected to supply myself with goat-flesh when I had no powder or shot left, breeding some up tame was my only way; when, perhaps, I might have them about my house like a flock of sheep.

But then it presently occurred to me that I must keep the tame from the wild, or else they would always run wild when they grew up. And the only way for this was to have some enclosed piece of ground, well fenced with hedge or pale, to keep them in so effectually, that those within might not break out, or those without break in.

This was a great undertaking for one pair of hands. Yet, as I saw there was an absolute necessity for doing it, my first piece of work was to find out a proper piece of ground, namely, where there was likely to be herbage for them to eat, water for them to drink, and cover to keep them from the sun.

Those who understand such enclosures will think I had very little contrivance when I pitched upon a place very proper for all these, being a plain open piece of meadow-land or savanna (as our people call it in the western colonies), which had two or three little rills of fresh water in it, and at one end was very woody. I say they will smile at my forecast, when I shall tell them I began my enclosing of this piece of ground in such a manner that my hedge or pale must have been at least two miles about! Nor was the madness of it so great as to the compass, for if it was ten miles about, I was like to have time enough to do it in. But I did not consider that my goats would be as wild in so much compass as if they had had the whole island, and I should have so much room to chase them in that I should never catch them.

My hedge was begun and carried on, I believe about fifty yards, when this thought occurred to me. So I presently stopped short, and for the first beginning I resolved to enclose a piece of about one hundred and fifty yards in length, and one hundred yards in breadth; which, as it would maintain as many as I should have in any reasonable time, so, as my flock increased, I could add more ground to my enclosure.

This was acting with some prudence, and I went to work with courage. I was about three months hedging in the first piece; and till I had done it, I tethered the three kids in the best part of it, and used them to feed as near me as possible, to make them familiar; and very often I would go and carry them some ears of barley, or a handful of rice, and feed them out of my hand; so that, after my enclosure was finished, and I let them loose, they would follow me up and down, bleating after me for a handful of corn.

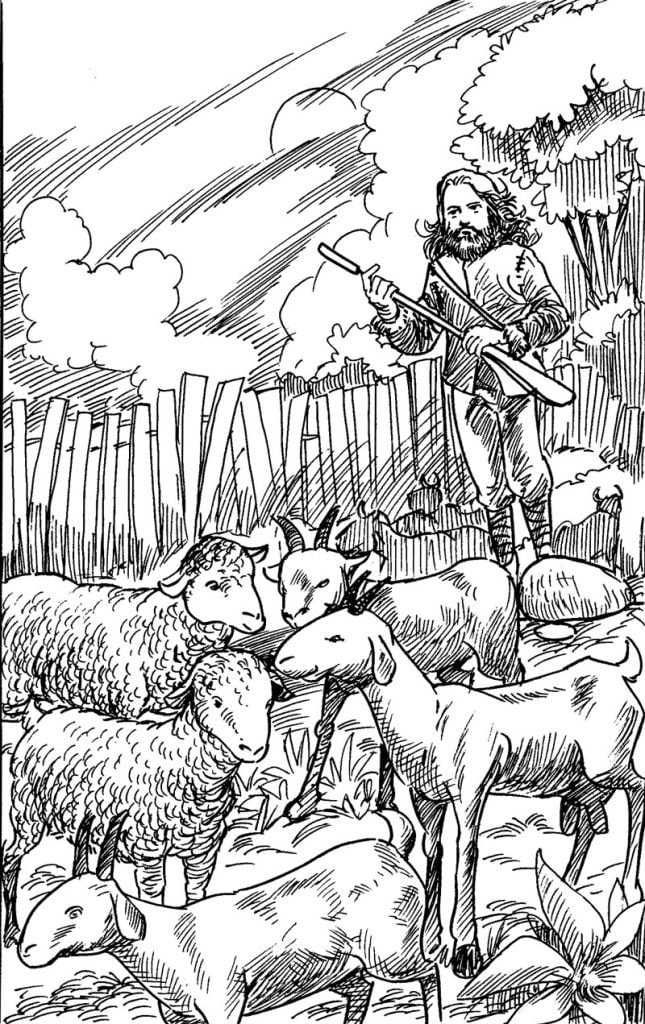

This answered my end. And in about a year and a half I had a flock of about three-and-forty—besides several that I took and killed for my food. And after that, I enclosed five several pieces of ground to feed them in, with little pens to drive them into, to take them as I wanted, and gates out of one piece of ground into another.

But this is not all; for now I not only had goat’s flesh to feed on when I pleased, but milk too—a thing which, indeed, in my beginning, I did not so much as think of, and which, when it came into my thoughts, was really an agreeable surprise. For now I set up my dairy, and had sometimes a gallon or two of milk in a day. And as Nature, who gives supplies of food to every creature dictates even naturally how to make use of it; so I, that had never milked a cow, much less a goat, or seen butter or cheese made, very readily and handily, though after a great many essays and miscarriages, made me both butter and cheese at last.

You are to understand that now I had, as I may call it, two plantations in the island: one my little fortification or tent, with the wall about it under the rock, with the cave behind me, which by this time I had enlarged into several apartments, or caves, one within another. One of these, which was the driest and largest, and had a door out beyond my wall or fortification—that is to say beyond where my wall joined to the rock—was all filled up with the large earthen pots of which I have given an account, add with fourteen or fifteen great baskets, which would hold five or six bushels each, where I laid up my stores of provision, especially my corn, some in the ear cut off short from the straw, and the other rubbed out with my hand.

As for my wall, made, as before, with long stakes or piles, those piles grew all like trees, and were by this time grown so big, and spread so very much, that there was not the least appearance to any one’s view of any habitation behind them.

Near this dwelling of mine, but a little farther within the land, and upon lower ground, lay my two pieces of cornground, which I kept duly cultivated and sown, and which dully yielded me their harvest in its reason; and whenever I had occasion for more corn, I had more land adjoining as fit as that.

Besides this I had my country seat, and I had now a tolerable plantation there also: for first, I had my little bower, as I called it, which I kept in repair—that is to say, I kept the hedge which circled it in, constantly fitted up to its usual height, the ladder standing always in the inside. I kept the trees, which at first were no more than my stakes, but had now grown very firm and tall—I kept them always so cut that they might spread and grow thick and wild, and make the more agreeable shade, which they did effectually to my mind. In the middle of this, I had my tent always standing, being a piece of a sail spread over poles set up for that purpose, and which never wanted any repair or renewing; and under this I had made me a squab or couch, with the skins of the creatures I had killed, and with other soft things, and a blanket laid on them; such as belonged to our sea-bedding, which I had saved, and a great watch—coat to cover me; and here, whenever I had occasion to be absent from my chief seat, I took my country habitation.

Adjoining to this I had my enclosures for my cattle, that is to say, my goats; and as I had taken an inconceivable deal of pains to fence and enclose this ground, so I was so uneasy to see it kept entire, lest the goats should break through, that I never left off till with infinite labour I had stuck the outside of the hedge so full of small stakes, and so near to one another, that it was rather a pale than a hedge, and there was scarce room to put a hand through between them; which, afterwards, when these stakes grew, as they all did in the next rainy season, made the enclosure strong like a wall; indeed, stronger than any wall.

In this place, also, I had my grapes growing, which I principally depended on for my winter store of raisins; and which I never failed to preserve very carefully, as the best and most agreeable dainty of my whole diet; and, indeed, they were not agreeable only, but physical, wholesome, nourishing, and refreshing to the last degree.

As this was also about half way between the other habitation and the place where I had laid up my boat, I generally stayed and lay here in my way thither; for I used frequently to visit my boat, and I kept all things about or belonging to her in very good order. Sometimes I went out in her to divert myself; but no more hazardous voyages would I go, nor scarce ever above a stone’s throw or two from the shore, I was so apprehensive of being hurried out of my knowledge again by the currents, or winds, or any other accident. But now I came to a new scene of life.

It happened one day about noon, going towards my boat, I was exceedingly surprised with the print of a man’s naked foot on the shore, which was very plain to be seen in the sand. I stood like one thunderstruck, or as if I had seen an apparition. I listened, I looked round me; I could hear nothing, nor see anything. I went up to a rising ground to look farther. I went up the shore and down the shore; but it was all one, I could see no other impression but that one. I went to it again to see if there were any more, and to observe if it might not be my fancy, but there was no room for that, for there was exactly the very print of a foot, toes, heel, and every part of a foot—how it came thither I knew not, nor could in the least imagination. But after innumerable fluttering thoughts, like a man perfectly confused and out of myself, I came home to my fortification, not feeling, as we say, the ground I went on, but terrified to the last degree, looking behind me at every two or three steps, mistaking every bush and tree, and fancying every stump at a distance to be a man. Nor is it possible to describe how many various shapes affrighted imagination represented things to me in; how many wild ideas were found every moment on my fancy, and what strange unaccountable—whimsies came into my thoughts by the way.

When I came to my castle, for so I think I called it ever after this, I fled into it like one pursued. Whether I went over by the ladder as first contrived, or went in at the hole in the rock which I called a door, I cannot remember; no, nor did I remember the next morning; for never frighted hare fled to cover, nor fox to earth, with more terror of mind than I to this retreat.