Chapter 8

We came to a valley in a great mountain, with water running down the middle and a shallow cave in the rock on one side. It was here Alan had been headed.

We slept in the cave, making our bed of heather bushes and covering ourselves with Alan’s greatcoat. There was a place we could build a small fire and grill the little trout’s we caught in the stream. Alan also taught me to use a sword.

On our first morning, Alan said to me, “We must get word sent to James.”

“And how?” said I, “We cannot leave here. Can you get the birds to talk for you?”

He got two sticks of wood, made them into a cross, and burnt the four ends of it in the coals. Then he turned and looked at me a little shyly.

“Could you lend me my button?” said he, “It seems strange to ask for a gift back, but I don’t want to cut another.” I gave him the button. He tied it to the cross and added a sprig of birch and another of fir.

“You see, David, said he, “I will steal down into the little village near here and set this in the window of a good friend of mine, John Breck Maccoll. He will know something is up by the cross.”

Then he will see my button, which was Duncan Stewart’s, and know that the son of Duncan is in need of him. He will know to come to the wood of birch and pine by the sprigs I have tied to the cross.”

“I see, man,” said I, teasing him, “you’re very smart. But wouldn’t it be simpler to write a note?”

“Yes, Mr. Balfour of Shaws, but it would be a job for John Breck to read it. He would have to go to school for two or three years, and we might get tired waiting for him.”

John Breck understood Alan’s sign and found us. He went to James Stewart with a note, but returned with an answer from Mrs. Stewart. James was in prison. She begged Alan not to let himself be captured. The money she sent was all that she could beg or borrow. Lastly, she sent one of the notices for our arrest that described our faces and our clothes. It seemed that Alan’s company was not only dangerous to my life, but also would be unhealthy for my pocketbook.

After looking at the notices for our arrest and seeing the amount of money that was on our heads, neither of us felt very safe. Alan and I left the cave that day.

After seven hours of hard travelling, we came to the end of a range of mountains. In front of us, there lay a piece of low, broken desert land which we had to cross. Much of it was red with heather; some had been burnt black in a fire. In another place, there was a forest of dead fir trees, standing like skeletons.

Sometimes we crawled from one heather bush to another heather bush for a full hour. We wore away the morning and about noon lay down in a thick bush of heather to sleep. Alan took the first watch, and it seemed to me I had only time to close my eyes before I was shaken up to take the second watch. But by this time, I was so weary that I could have slept twelve hours at a stretch. I had the taste of sleep in my throat, and the humming of the wild bees was like a sleeping potion. Every now and then, I would jump and find that I had been dozing.

The last time I woke I seemed to come back from farther away and thought the sun had moved far in the sky. When I looked around me on the moor, my heart sank. The soldiers were spread out in the shape of a fan, riding their horses and searching the heather.

I woke Alan. He glanced at the soldiers, then at the position of the sun, and gave me a quick look, “We’ll have to play at being rabbits,” said he, “Do you see the mountain over there?”

“Yes,” said I.

“Well, then,” said he, “let’s head for that.”

“But, Alan,” cried I, “that will take us across the path of the soldiers!”

“I know,” said he, “but if we are taken back to Appin, we are two dead men. So now David, be brisk!”

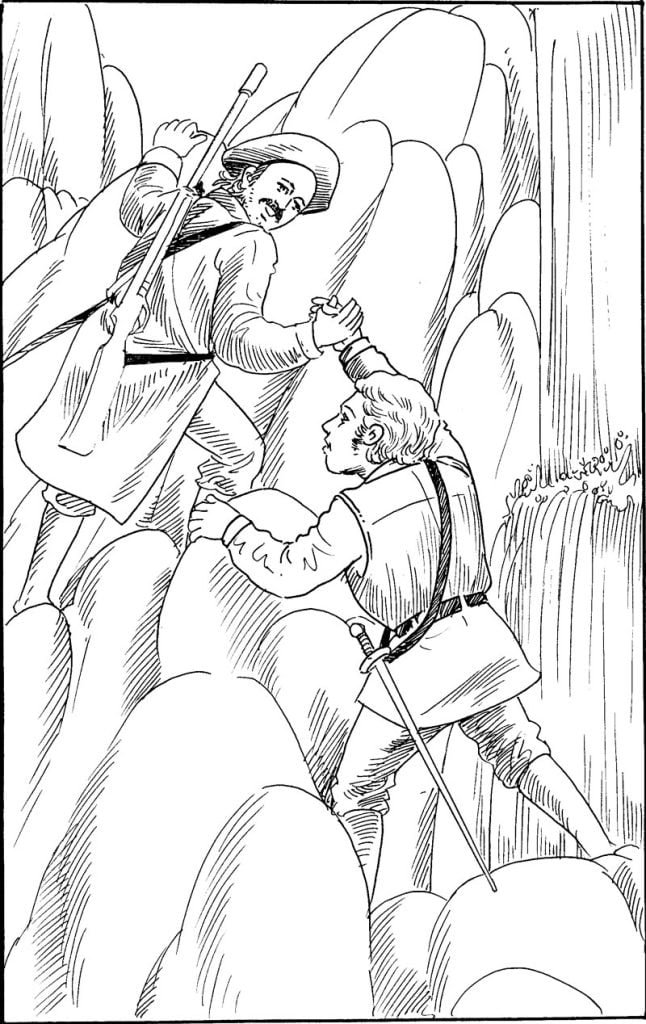

Nothing but the fear of Alan gave me enough of a false kind of courage to go on. We ran and crawled, crawled and stumbled, until the sun fell. Never a word passed between us. Neither of us really looked where we were running to. It was plain that Alan must have been as stupid with weariness as I was, or we would not have walked into an ambush like blind men. The heather gave a sudden rustle; three or four ragged men leapt out, and the next moment we were lying on our backs with knives at out throats.

I heard Alan and another whispering in Gaelic. The knives were removed, our weapons were taken away, and we were left sitting in the heather under guard.

“They are Cluny’s men,” said Alan.

Cluny Macpherson was chief of a Highland clan and had been one of the leaders in the great rebellion six years before. There was a price on his head, as there was on ours. We had been caught in his territory, but he had heard of Alan Breck, and we weren’t likely to be harmed. Alan was clearly at ease. As soon as the men had set us down, he had fallen fast asleep. There was no such thing possible for me. I lay awake.

Cluny sent word that we should come to him. I was feverish, tried and hungry, and my head felt silly and light. I could not walk alone. Alan had the men half-carry me along and I felt I was in a dream.

Just before the rocky face of the cliff could be seen above the foliage, we found that strange house which was known as ‘Cluny’s Cage.’ A tree which grew out from the hillside was the living beam of the roof. Earth had been filled in along the slope to make a level floor. The bulls were made of woven branches covered with moss. The whole house was shaped like an egg and was large enough to shelter five or six persons comfortably.

This was only one of Cluny’s hiding places; he had caves and underground chambers in different parts of his country. He moved from one to the other as soldiers came near or moved away.

It was certainly a strange place, and we had a strange host. In his long hiding, Cluny had taken on the habits of an old maid. He had a certain place where no one else could sit, and the cage was arranged a certain way which no one could disturb.

He sometimes visited or received visits from his wife and one or two his nearest friends at night, but for the most part he lived along and only talked to the sentinels and the men who waited on him in the cage. Although he kept himself so alone yet he still knew all the business of the clan and made the final decision on clan matters and disputes.

I remembered little of the few days Alan and I spent there. I was feverish and was in bed and asleep most of the time. I did know that Cluny was suspicious of me because I would not play cards with them. My father had been very much against card playing and gambling, and I shared his dislike for the game.

And I knew that Alan lost all our money to Cluny in their card game. He came to me while I was half-asleep and asked for a loan. I gave it to him without thinking, and he lost it.

We were none of us talking to each other when Alan and I set out. I had told Cluny that I wouldn’t take back as a gift the money he had won fairly from Alan. He returned the money because he knew he could not let two friends go out without money when they were wanted by the law, but he was not happy to do it. Alan was quiet and feeling guilty for losing the money. I had nothing to say to either of them. I was still tired and a bit sick and wished I were alone.