Chapter-9

“That darned captain would have to stop the ship just as we were about to leave,” Ned muttered angrily the next day.

“Yes, Ned,” I replied, “he had to see his banker.”

“His banker?” Ned looked puzzled.

“Or rather his bank!” I then told him the story of the treasure at Vigo Bay.

“Well, everything’s not over yet,” he said.

“For now it is,” I cried, “Look at the map. We’re hundreds of miles from any land.”

I must admit I was rather pleased still to be on board the Nautilus, and I returned to my work eagerly. But I was even more pleased that night when I received an unexpected visit in my cabin from Captain Nemo.

“Professor,” he said, “you have seen the ocean depths so far only in daylight. How would you like to see them now at night?”

“Very much, Captain,” I replied, rather curious about this new excursion on which only I was invited.

Within minutes we were in our diving suits, walking on the ocean floor a thousand feet beneath the dark Atlantic.

It was almost midnight. The water was completely black, but Captain Nemo pointed to a reddish glow about two miles away from us. As we walked towards the glow, the flat ground started to rise and become quite rocky. The strange thing about these rocks was that they were laid out in a regular pattern—almost like a man-made road. I had no way of questioning Captain Nemo about it for I didn’t know the sign language he used with his crew underwater.

We were actually climbing a mountain, and the reddish glow was lighting up the whole area as we got closer to it. Captain Nemo pushed through the rocks and the forest of dead trees turned to stone like a man who had travelled this path many times.When he reached the top, I looked out into the distance. There, unbelievable as it may seem, stood an underwater volcano. Its large crater was spitting out torrents of lava, giving the water its reddish glow.

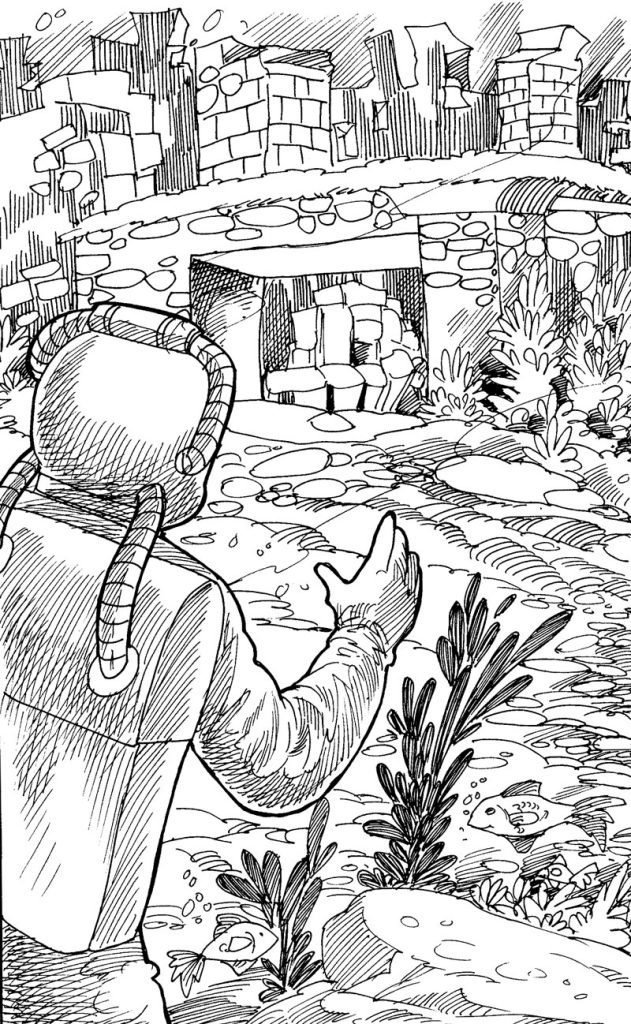

As my eyes travelled to the base of the volcano, I was stunned to see a ruined, crumbled town. Its roofs were caved in, its temples were fallen, and its columns were lying on the ground. Off to one side lay the remains of a dock and parts of a ship. Further on were long lines of crumbled walls and deserted streets. Here was an entire city buried beneath the sea.

What part of the world had been swallowed up like this? I had to know I tugged at Captain Nemo’s sleeve and pointed. He picked up a stone, went over to a black rock, and wrote a single word—ATLANTIS.

Suddenly, everything became clear. This was the ancient continent which once stretched from Africa to America. It was supposedly struck by a giant earthquake and, in a single day, it sank into the sea.

Many historians believed Atlantis was only a legend, but here I was, standing on a mountain of this lost continent, touching ruins thousands of centuries old. Would this volcano one day bring these sunken ruins back to the surface again? And would this miracle of the past be revealed to man? My head was spinning with these thoughts as we returned to the Nautilus.

I spent weeks at my notes detailing all the wonders of Atlantis. But one day, Ned burst in and announced that we had just passed the tip of South America without turning west into the Pacific. We were still heading south, but south meant the icy wastelands of Antarctica and the South Pole!

We ran up on deck to ask Captain Nemo. Just as we climbed out of the hatch, Ned spied a herd of whales a mile from the ship.

“Can I go and hunt them, Captain?” he asked, “Just to keep my harpoon in practice.”

“Mr. Land,” replied the captain coldy, “those are kind, playful black whales. They have enough trouble surviving attacks from their natural enemies, the sperm whales. They don’t need you getting into the act.”

Ned’s face turned purple with rage, but the captain ignored him as he went on. “The black whales are going to be in trouble soon enough. Look at these dots behind them.”

We turned and looked out to sea.

“Those, gentlemen,” said Captain Nemo, “are the cruel, destructive sperm whales! People have a right to kill them. And that is precisely what the Nautilus will do with the steel spur on her prow.”

We went below and the Nautilus dived. Ned, Conseil, and I took our places at the window while Captain Nemo went to the helmsman’s compartment to lead the attack.

The Nautilus became a fierce weapon in the hands of Captain Nemo as he plunged its steel spur into whale after whale, cutting each one into two twisting halves. The battle raged for hours, then the sea was calm.

The Nautilus surfaced, and we rushed up on deck. The sea was covered with cut apart bodies floating in an ocean of blood.

As February turned into March, and we continued heading south, we began to see icebergs. But we steered between them until they became joined together by ice fields long, unbroken plains of solid ice. For a while, the Nautilus was able to split the ice fields open with her strong prow. But finally, on March 18, we could go no further. We were up against a chain of ice mountains whose sharp peaks rose like thin needles three hundred feet into the air.

“It’s the Great Ice Barrier,” cried Ned.

And truly it was. It was the one obstacle that no ship had ever been able to get through. We would have to turn back.

But as I looked back, I saw that was impossible too. All the passages behind us had frozen together, closing us in.

“We’re trapped, Captain,” I cried.

“Oh, Professor,” said the captain calmly, “you always worry. Not only will the Nautilus free herself, but she will continue on and take us to the South Pole. We shall discover the Pole together. Where others have failed, I Captain Nemo, shall succeed.”

“I’d like to believe you, Captain,” I replied, “but do you plan to put wings on the Nautilus and fly over the Great Ice Barrier?”

“No, Professor! Not over it, under it!”

Suddenly I realized that this just might be possible. For every foot of iceberg above water, there are three feet below. So, these three-hundred-foot-high ice mountains only went down nine hundred feet below the surface. And nine hundred feet was a mere nothing for the Nautilus to dive.

Captain Nemo ordered everyone below, and the Nautilus started down. Sure enough, when he reached a depth of nine hundred feet, we floated freely in the water.

For the next three days, we sailed underneath the ice, but continued on our southerly course.

We finally surfaced on March 21. All of us rushed up on deck. A few icebergs were scattered here and there, but the sky was full of birds and the water, full of fish. At 37 degree it felt like spring.

“Are we at the South Pole?” I asked.

“I’ll take out position at noon and know for sure,” answered Captain Nemo, “If, at noon, the sun is cut exactly in half when we look at the northern horizon, then we will be at the South Pole.”

So the Nautilus cruised slowly along the surface for several hours until we reached a mass of rocks surrounded by a beach. The dinghy was put to sea and Captain Nemo, Conseil and I got in. We rowed towards the sandy shore swarming with penguins, seals and walruses.

“Monsieur,” I said to Captain Nemo, “if this is the South Pole, you should have the honour of being the first to set foot on it.”

“Yes, Professor,” he said, “and the only reason I’m setting foot on dry land is because no other human being has been here before.”

Captain Nemo then jumped out of the dinghy and climbed up on a rock. Conseil and I waited several minutes, then followed.

I checked my watch. It was noon.

Captain Nemo lifted his telescope and pointed it to the north. Then he announced solemnly, “Today, March 21, 1868, I, Captain Nemo, reached the South Pole. I now take possession of this part of the world.”

Then he unrolled a black flag with a gold N on it and planted it in the rock.