Chapter 1

There lived a Mole in the forest. He was very hard-working. Right from morning till evening he would clean his little home for the spring season. He would use brooms and dusters to tidy his little home. After the cleaning was over, he would be dead tired. He had dust all over his body – in his eyes, nose and even in his ears. He had an aching back. His arms were tired a lot. Now he got fed up with the cleaning work. He threw away brooms and dusters and got out of his house without putting on his coat. He went on and on in the bright sunlight. At last he reached the meadow where he rolled himself in the warm grass. He had all fun and frolic there.

‘This is fine!’ he said to himself. ‘This is better than whitewashing!’ The sunshine struck hot on his fur, soft breezes caressed his heated brow.

It all seemed too good to be true. Hither and thither through the meadows he rambled busily, along the hedgerows, across the copses, finding everywhere birds building, flowers budding, leaves thrusting—everything happy, and progressive, and occupied. And instead of having an uneasy conscience pricking him and whispering ‘whitewash!’ he somehow could only feel how jolly it was to be the only idle dog among all these busy citizens. After all, the best part of a holiday is perhaps not so much to be resting yourself, as to see all the other fellows busy working.

As he sat on the grass and looked across the river, a dark hole in the bank opposite, just above the water’s edge, caught his eye, and dreamily he fell to considering what a nice snug dwelling-place it would make for an animal with few wants and fond of a bijo riverside residence, above flood level and remote from noise and dust. As he gazed, something bright and small seemed to twinkle down in the heart of it, vanished, then twinkled once more like a tiny star. But it could hardly be a star in such an unlikely situation; and it was too glittering and small for a glow-worm. Then, as he looked, it winked at him, and so declared itself to be an eye; and a small face began gradually to grow up round it, like a frame round a picture.

A brown little face, with whiskers.

A grave round face, with the same twinkle in its eye that had first attracted his notice.

Small neat ears and thick silky hair.

It was the Water Rat!

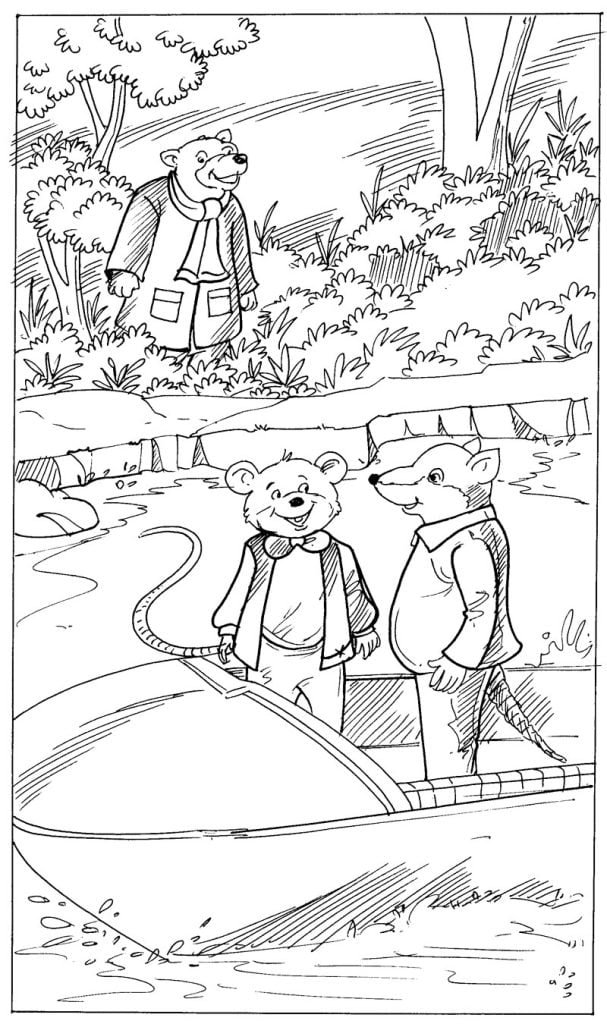

Then the two animals stood and regarded each other cautiously.

The Rat said nothing, but stooped and unfastened a rope and hauled on it; then lightly stepped into a little boat which the Mole had not observed. It was painted blue outside and white within, and was just the size for two animals; and the Mole’s whole heart went out to it at once, even though he did not yet fully understand its uses.

The Rat sculled smartly across and made fast. Then he held up his forepaw as the Mole stepped gingerly down. ‘Lean on that!’ he said, ‘Now then, step lively!’ and the Mole to his surprise and rapture found himself actually seated in the stern of a real boat.

The Mole never heard a word he was saying. Absorbed in the new life he was entering upon, intoxicated with the sparkle, the ripple, the scents and the sounds and the sunlight, he trailed a paw in the water and dreamed long waking dreams. The Water Rat, like the good little fellow he was, sculled steadily on and forebore to disturb him.

‘I like your clothes awfully, old chap,’ he remarked after some half an hour or so had passed, ‘I’m going to get a black velvet smoking-suit myself some day, as soon as I can afford it.’

‘I beg your pardon,’ said the Mole, pulling himself together with an effort, ‘You must think me very rude; but all this is so new to me. So—this—is—a—River!’

‘THE River,’ corrected the Rat.

‘And you really live by the river? What a jolly life!’

‘Well, of course—there—are others,’ explained the Rat in a hesitating sort of way.

‘Weasels—and stoats—and foxes—and so on. They’re all right in a way—I’m very good friends with them—pass the time of day when we meet, and all that—but they break out sometimes, there’s no denying it, and then—well, you can’t really trust them, and that’s the fact.’

The Mole knew well that it is quite against animal-etiquette to dwell on possible trouble ahead, or even to allude to it; so he dropped the subject.

Leaving the main stream, they now passed into what seemed at first sight like a little land-locked lake. Green turf sloped down to either edge, brown snaky tree-roots gleamed below the surface of the quiet water, while ahead of them the silvery shoulder and foamy tumble of a weir, arm-in-arm with a restless dripping mill-wheel, that held up in its turn a grey-gabled mill- house, filled the air with a soothing murmur of sound, dull and smothery, yet with little clear voices speaking up cheerfully out of it at intervals. It was so very beautiful that the Mole could only hold up both forepaws and gasp, ‘O my! O my! O my!’

There was a rustle behind them, proceeding from a hedge wherein last year’s leaves still clung thick, and a stripy head, with high shoulders behind it, peered forth on them.

‘Come on, old Badger!’ shouted the Rat.

The Badger trotted forward a pace or two; then grunted, ‘H’m! Company,’ and turned his back and disappeared from view.

The two animals looked at each other and laughed.

From where they sat they could get a glimpse of the main stream across the island that separated them; and just then a wager-boat flashed into view, the rower—a short, stout figure—splashing badly and rolling a good deal, but working his hardest. The Rat stood up and hailed him, but Toad—for it was he—shook his head and settled sternly to his work.

The Mole looked down. The voice was still in his ears, but the turf whereon he had sprawled was clearly vacant. Not an Otter to be seen, as far as the distant horizon.

But again there was a streak of bubbles on the surface of the river.

The Rat hummed a tune, and the Mole recollected that animal- etiquette forbade any sort of comment on the sudden disappearance of one’s friends at any moment, for any reason or no reason whatever.

The afternoon sun was getting low as the Rat sculled gently homewards in a dreamy mood, murmuring poetry-things over to himself, and not paying much attention to Mole. But the Mole was very full of lunch, and self-satisfaction, and pride, and already quite at home in a boat (so he thought) and was getting a bit restless besides: and presently he said, ‘Ratty! Please, I want to row, now!’

The Rat shook his head with a smile. ‘Not yet, my young friend,’ he said, ‘wait till you’ve had a few lessons. It’s not so easy as it looks.’

The Mole was quiet for a minute or two. But he began to feel more and more jealous of Rat, sculling so strongly and so easily along, and his pride began to whisper that he could do it every bit as well. He jumped up and seized the sculls, so suddenly, that the Rat, who was gazing out over the water and saying more poetry-things to himself, was taken by surprise and fell backwards off his seat with his legs in the air for the second time, while the triumphant Mole took his place and grabbed the sculls with entire confidence.

The Mole flung his sculls back with a flourish, and made a great dig at the water. He missed the surface altogether, his legs flew up above his head, and he found himself lying on the top of the prostrate Rat. Greatly alarmed, he made a grab at the side of the boat, and the next moment—Sploosh!

Over went the boat, and he found himself struggling in the river.

The Rat got hold of a scull and shoved it under the Mole’s arm; then he did the same by the other side of him and, swimming behind, propelled the helpless animal to shore, hauled him out, and set him down on the bank, a squashy, pulpy lump of misery.

When the Rat had rubbed him down a bit, and wrung some of the wet out of him, he said, ‘Now, then, old fellow! Trot up and down the towing-path as hard as you can, till you’re warm and dry again, while I dive for the luncheon-basket.’

So the dismal Mole, wet without and ashamed within, trotted about till he was fairly dry, while the Rat plunged into the water again, recovered the boat, righted her and made her fast, fetched his floating property to shore by degrees, and finally dived successfully for the luncheon-basket and struggled to land with it.

When they got home, the Rat made a bright fire in the parlour, and planted the Mole in an arm-chair in front of it, having fetched down a dressing-gown and slippers for him, and told him river stories till supper-time.

❒