Chapter 7

Maxim went into the little room and shut the door. Robert came in a few minutes afterwards to clear away the tea. I stood up, my back turned to him so that he should not see my face. I wondered when they would begin to know, on the estate, in the servants’ hall, in Kerrith itself. I wondered how long it took for news to trickle through. I could hear the murmur of Maxim’s voice in the little room beyond I had a sick expectant feeling at the pit of my stomach.

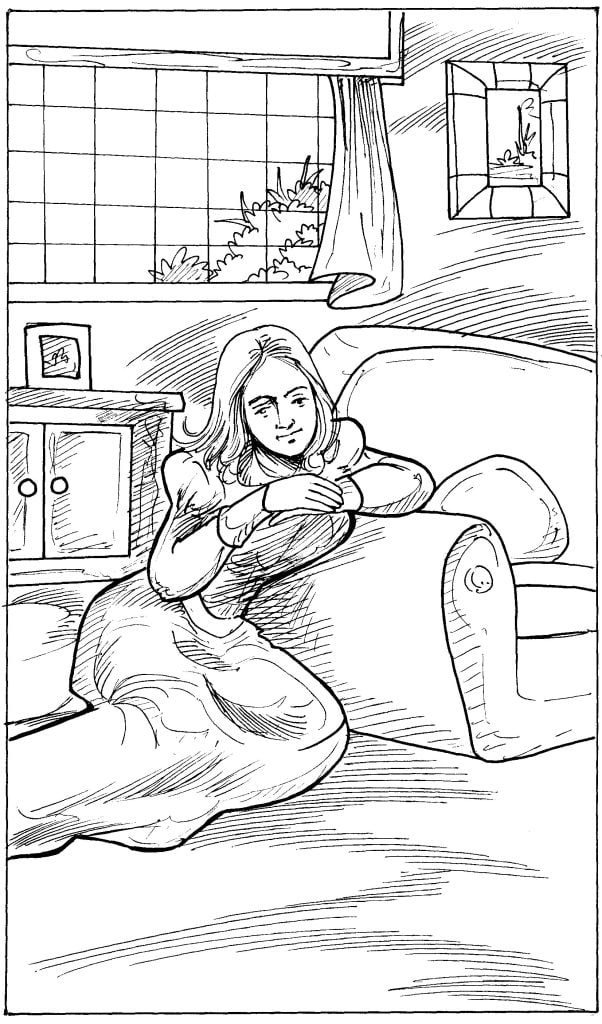

The sound of the telephone ringing seemed to have woken every nerve in my body. I had sat there on the floor beside Maxim in a sort of dream, his hand in mine, and my face against his shoulder. I had listened to his story and part of me went with him like a shadow in his tracks. I too had killed Rebecca; I too had sunk the boat there in the bay. I had listened beside him to the wind and water. I had waited for Mrs. Danvers’ knocking on the door.

All this I had suffered with him, all this and more besides. But the rest of me sat there on the carpet, unmoved and detached, thinking and caring for one thing only, repeating phrase over and over again. “He did not love Rebecca, he did not love Rebecca.” Now, at the ringing of the telephone, these two selves merged and became one again. I was the self that I had always been, I was not changed. But something new had come upon me that had not been before. My heart, for all its anxiety and doubt, was light and free. I knew then that I was no longer afraid of Rebecca. I did not hate her any more.

Now that I knew her to have been evil and vicious and rotten I did not hate her any more. She could not hurt me. I could go to the morning-room and sit-down at her desk and touch her pen and look at her writing on the pigeon-holes, and should not mind. I could go to her room in the west wing, stand by the window even as I had done this morning, and I should not be afraid.

Rebecca’s power had dissolved into the air, like the mist had done. She would never haunt me again. She would never stand behind me on the stairs, sit beside me in the dining-room, lean down from the gallery and watch me standing in the ball.

Maxim had never loved her. I did not hate her any more. Her body had come back, her boat had been found with its queer prophetic name, Je Reviens, but I was free of her forever. I was free now to be with Maxim, to touch him, and hold him, and love him. I would never be a child again.

It would not be I, I, I any longer, it would be we, it would be us. We would be together. We would face this trouble together, he and I.

Captain Searle, and the diver, and Frank, and Mrs. Danvers, and Beatrice, and the men and women of Kerrith reading their newspapers, could not break us now. Our happiness had not come too late. I was not young any more. I was not shy. I was not afraid I would fight for Maxim.

I would lie and perjure and swear, I would blaspheme and pray. Rebecca had not won. Rebecca had lost Robert had taken away the tea and Maxim came back into the room. “It was Colonel Julyan,” he said, “he’s just been talking to Searle. He’s coming out with us to the boat to-morrow. Searle has told him.”

“Why Colonel Julyan, why?” I said, “He’s the magistrate for Kerrith. He has to be present.”

“What did he say?”

“He asked me if I had any idea whose body it could be.”

“What did you say?”

“I said I did not know. I said we believed Rebecca to be alone. I said I did not know of any friend.”

“Did he say anything after that?”

“Yes.”

“What did he say?”

“He asked me if I thought it possible that I made a mistake when I went up to Edgecoombe.”

“He said that? He said that already?”

“Yes.” I felt his finger tips on the scalp of my head. Sometimes he kissed me. Sometimes he said things to me. There were no shadows between us any more, and when we were silent it was because the silence came to us of our own asking. I wondered how it was I could be so happy when our little world about us was so black.

It was a strange sort of happiness. Not what I had dreamt about or expected. It was not the sort of happiness I had imagined in the lonely hours. There was nothing feverish or urgent about this. It was a quiet, still happiness.

The library windows were open wide, and when we did not talk or touch one another we looked at the dark dull sky. It must have rained in the night for when I woke the next morning, just after seven, and got up, and looked out of the window, I saw the roses in the garden below were folded and drooping, and the grass banks leading to the woods were wet and silver.

There was a little smell in the air of mist and damp, the smell that comes with the first fall of the leaf. I wondered if autumn would come upon us two months before her time. Maxim had not woken me when he got up at five. He must have crept from his bed and gone through the bathroom to his dressing-room without a sound. He would be down there now, in the bay, with Colonel Julyan, and Captain Searle, and the men from the lighter.

The lighter would be there, the crane and the chain, and Rebecca’s boat coming to the surface. I thought about it calmly, coolly, without feeling. I pictured them all down there in the bay, and the little dark hull of the boat raising slowly to the surface, sodden, dripping, the grass-green seaweed and the shells clinging to her sides. When they lifted her on to the lighter the water would stream from her sides, back into the sea again.

The wood of the little boat would look soft and grey, pulpy in places. She would smell of mud and rust, and that dark black weed that grows deep beneath the sea beside rocks that are never uncovered. Perhaps the name-board still hung upon her stem. Je Reviens. The lettering greensand faded. The nails rusted through. And Rebecca herself was there, lying on the cabin floor.

❒