Chapter-3

I felt very neglected in the land of Laputa, since the inhabitants seemed interested only in mathematics and music, and were far superior to me in their knowledge. I got bored by their conversation and wanted to leave. There was one lord of the court whom I found to be intelligent and curious, but who was regarded by the other inhabitants of Laputa as stupid because he had no passion for music. I requested this lord to seek permission of the king to let me leave the island.

On 16th February, I took leave of the king and the court. The king gave me a present worth two hundred English pounds. He also gave me a letter of recommendation addressed to one of his friends in Lagado, the metropolis, who would help me there. The island then hovered over a mountain about two miles from it. I was let down from the lowest gallery in the same manner as I had been taken up. I soon found out the person’s house to which I was recommended. I presented my letter from his friend and he received me very gently. The lord, whose name was Munodi, provided me with an apartment in his own house. I continued to live there during my stay in Lagado. I was treated in the most hospitable manner.

The next morning after my arrival, Munodi took me in his chariot to visit the town which was about half the size of London. The house were very strangely built and most of them out of repair. The people were quite strange there. They walked about the streets in haste, looked wild and most of them were generally in rags. The soil was badly cultivated and the people appeared miserable. We then travelled to Munodi’s country house. We passed many barren fields but then arrived in a lush green area which belonged to Munodi’s estate. He told me that the other lords criticized him heavily for the mismanagement of his land.

Munodi was a person of the first rank, and had been the governor of Lagado for some years. But he was discharged for insufficiency by a cabinet of ministers. However, the king treated him well and regarded him as a well-behaved man but of a low contemptible understanding. At last, we came to a house which was indeed a good structure. It was built in accordance to the ancient architecture. The fountains, gardens, walks, avenues and groves were all designed with exact judgment and taste.

Munodi explained that (forty years ago) some people went to Laputa and had returned with new ideas about mathematics and art. They decided to establish an academy in Lagado to develop new theories on agriculture and construction. They wanted to initiate projects to improve the lives of the inhabitants of the city. However, the theories had never produced any results and the new techniques had left the country in ruin. He encouraged me to visit the academy. I was glad to do since I too was once fascinated by such projects.

Munodi himself did not want to got to the academy because of his reputation there. So, he recommended me to a friend of his, who would accompany me to the academy. This academy was not an entire single building, but a continuation of several houses on both sides of a street. I was received very kindly by the warden and went for many days to the academy. Every room in it had one or more projectors and I entered about five hundred rooms.

The first man I saw was a strange man. His hands and face were dirty and his hair and beard were long and ragged. His clothes, shirt and skin were of the same colour. I came to know later that he had been involved in a project of extracting sunbeams out of cucumbers for the past eight years. He told me that there was no doubt he would be able to supply the governor’s gardens with sunshine at a reasonable rate in another eight years. But he complained that his means were low and pestered me to give him something as an encouragement to promote that project.

I gave him a small present out of the money that Munodi had handed over to me for his purpose. He knew their practice of begging from all who went to see them.

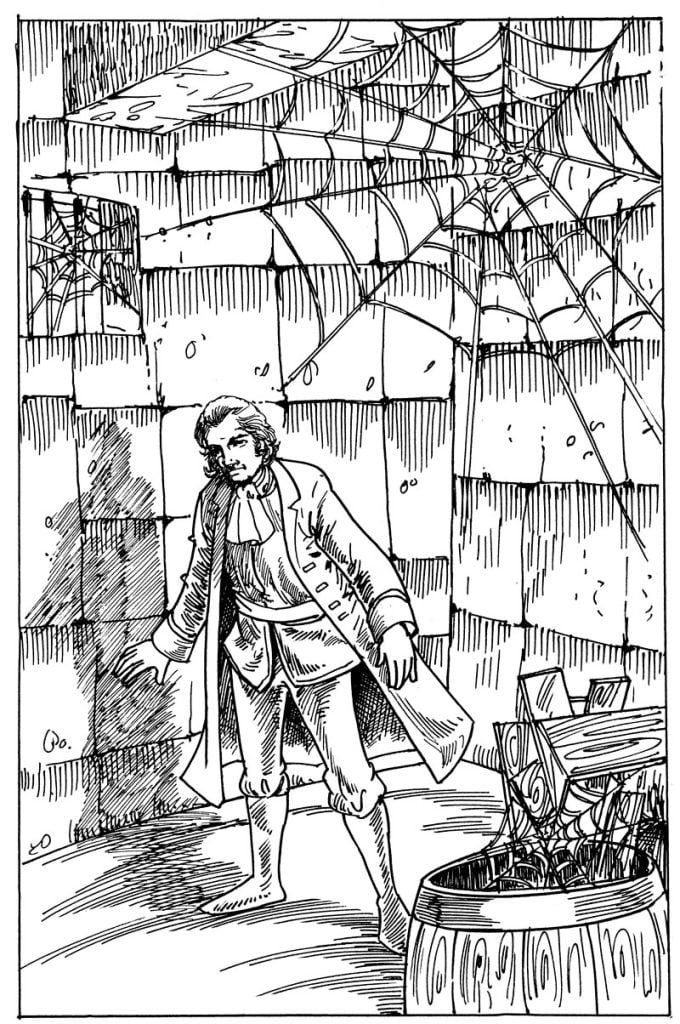

I went into another room where the walls and ceiling were all hung round with cobwebs. There was a very narrow passage for the artist to go in and out. As I entered the room, he called aloud to me, “Do not disturb the webs.” He continued further, “By employing spiders the charge of dyeing silks could be wholly saved.”

I was fully convinced when he showed me a vast number of files most beautiful coloured with which he fed his spiders. He assured us that the webs would take a tincture from them. He was in search of proper food for the files of certain gums, oils and other glutinous matter which would give strength and consistence of the threads.

I also met a scientist who tried to turn human excrement back into food. Another attempted to turn ice into gun-powder. Together with this, he wrote a treatise about the malleability of fire and hoped to have it published some day. An architect was designing a way to build houses from the roof down. A blind painter taught his blind apprentices to mix colours according to smell and touch. An agronomist was designing a method of ploughing fields with hogs by first burying food in the ground and then letting the hogs loose to dig it out. A doctor in another room tried to cure his patients by blowing air through them. He tried to revive a dog that he had killed thinking of curing it in this way.

There was an astronomer who had undertaken the task to place a sun-dial upon the great weathercock on the town-house. He had adjusted the annual and diurnal motions of the earth and sun so as to answer and coincide with all accidental turnings of the wind.

By now, I had seen only one side of the academy. I met one illustrious person who was called ‘the universal artist’. He told us that his thoughts for the improvement of human life for the past thirty years he had been employing. He had two large rooms full of wonderful curiosities, and fifty men at work. Some were condensing air into a dry tangible substance, by extracting the nitre and letting the aqueous or fluid particles percolate. Others softened marble for pillows and pin-cushions; others petrified the hoofs of a living horse to preserve them from foundering.

The artist himself was at that time busy upon two great designs. The first one was to sow land which he demonstrated by several experiments, but I was not skilful enough to understand. The other was to make a certain composition of gums, minerals and vegetables and applied to a young lamb to prevent the growth of wool upon it. He hoped to propagate the breed of naked sheep all over the kingdom within a reasonable time.

On the other side of the academy, there were people engaged in speculative learning. The first professor I saw was in a very large room, with forty pupils. He was employed in a project for improving speculative knowledge, by practical and mechanical operations. He said that the world would soon realize its usefulness. He said, “Such a noble and dignified thought never sprang up in any other man’s mind. Everyone knew how laborious the usual method was of attaining arts and sciences. By my contrivance the most ignorant person at a reasonable cost and with a little labour might write books on philosophy, poetry, politics, laws, mathematics and theology without the least assistance from any genius or study.”

He then led me to the place where all his pupils stood in order. It was a twenty feet square, placed in the middle of the room. The superficies were composed of several bits of wood about the size of a dye but some larger than others. They were linked together by slender wires. These bits of wood were covered on every square with paper pasted on them. On these papers were written all the words of their language in their several moods, tenses and declensions, but without any order.

The professor then asked me to observe how he was going to set his engine at work. He gave a command and each of the pupils held an iron handle. There were forty such handles fixed round the edges of the frame. When all of them held the iron handles, they gave a sudden turn. As a result, the whole disposition of the words was entirely changed. He then commanded thirty-six of the pupils to read the several lines softly as they appeared upon the frame. Wherever they found three of four words together, that might make part of a sentence they dictated to the four remaining boys who were scribes. This work was repeated three or four times. At every turn, the engine was so contrived that the words shifted into new places as the square bits of wood moved upside down.

The young students were employed in at work six hours a day. The professor showed me several volumes in large folio already collected of broken sentences which he intended to piece together. Out of those rich materials, he wanted to give the world a complete volume of all arts and sciences. He said that the method might be still improved if the public would raise a fund for making and employing five hundred such frames in Lagado.

He said, “This invention has crept in my mind since I was a youth. I have emptied the whole vocabulary into this frame and made the strictest computation of the general proportion which was there in books between the numbers of particles, nouns, verbs and other parts of speech.”

A linguist in another room attempted to remove all the elements of language except nouns. He claimed that refining the language in that way would make it more concise and prolong lives, since every word spoken was detrimental to the human body. Another professor tried to teach mathematics by making his students wafers that had mathematical proofs written on them.

In the school of political projectors, I must say that some of them were insane. They proposed that administrators should be chosen for their wisdom, talent and skill. They also said that ability and virtue should be rewarded and that ministers should be chosen for their love of public good. One scientist proposed to improve state business by kicking and pinching ministers so as to make them less forgetful. Another said that he would expose treacherous plots by examining excrement because people were most thoughtful on the toilet.

There was a most imaginative doctor who seemed to be perfectly versed in the whole nature and system of government. This illustrious person had very usefully employed his studies in finding out effectual remedies for all the diseases and corruptions of public administration for those who governed as well as for those who obeyed.

I heard a very hot debate between two professors about the most extensive and efficient ways and means of raising money without grieving the subject. The first stated, “The just method would be to lay a certain tax upon vices and folly; and the sum should be fixed upon every man to be rated, after the fairest manner by a jury of his neighbours.”

The second was of an opinion directly contrary, “To tax those qualities of an individual, for which men chiefly value them. The rate could be more or less according to the degrees of excelling; the decision whereof should be left entirely to their own selves.”

Another said, “The highest tax must be imposed upon men who were the greatest favourites of the other sex, and the assessments, according to the number and nature of the favours they had received. Wit, valour and politeness should be proposed to be largely taxed and collected according to the quantity each one possessed.”

The woman were proposed to be taxed according to their beauty and skill in dressing. They too had the same privilege as the men to be determined by their own judgment. But constancy, chastity, good sense and good nature were not rated because they would not bear the charge of collecting. The professor made great acknowledgements to communicate these observations. He also promised to make an honourable mention of me in his treatise.

Finally, I saw nothing in this country for which I could stay longer. So I began to think of returning home to England.