Chapter-8

Days and weeks slipped by. During my probation at Spenlow and Jorkins I found I liked the work, and was apprenticed. To celebrate the occasion, Mr Spenlow invited me to spend the weekend at his country house in Norwood. At the end of the workday on Friday, he and I drove to Norwood in his carriage. We talked of civil law and the courts and the general direction Parliament seemed to be moving, and the trip passed quickly.

The house—a large, white-brick place with perfectly cut gardens clustered with trees and brick walks—was welcoming, cheerfully lighted and colourfully decorated in the rich style of a hunting estate.

Mr Spenlow was a widowed father of one daughter who had just finished her education in Paris and returned home. He called to his daughter as soon as we entered the hallway. I had just handed my coat to the butler and turned towards the stairs when my life’s course was for ever altered by his words: “Mr Copperfield, my daughter Dora.”

Yes. One word was all I could think. Yes. In an instant, she was all the world to me—I was swallowed up in a flood of love. There was no pausing on the brink, no looking down into the current, no glancing back. I was gone, head first, with no hope, no desire for rescue.

At Spenlow’s urging, I went upstairs to unpack and dress for dinner, but spent the time instead sitting on the edge of my bed chewing on my luggage key and thinking of Dora—bright-eyed, lovely Dora.

I was sure we had dinner. I know there were other people there. But who they were and what we ate I couldn’t say. I only remembered sitting beside Dora, enjoying her rich voice and warm laugh. When she tapped my arm to ask if the untouched food didn’t suit me, I shivered so badly my coffee sloshed down the front of my starched white shirt.

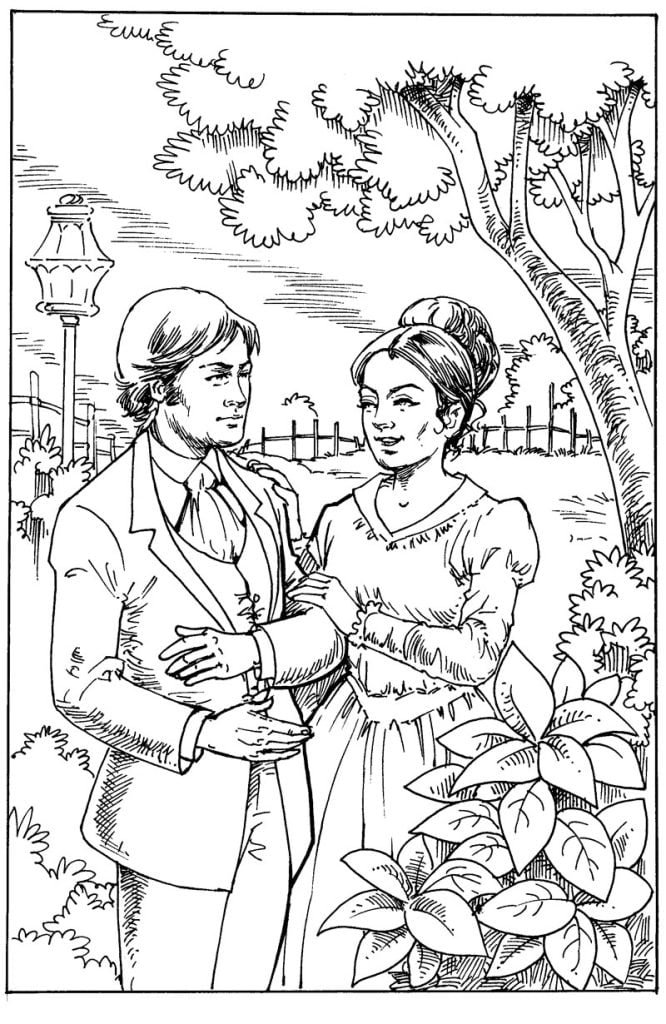

I couldn’t sleep that night and was up before the birds. The garden walks were wet with drew, cool and misty. I hadn’t been walking there long, thinking of where my heart had gone and what I was to do without it, when I turned a corner and met her.

I stuttered some silly greeting. “Isn’t this a fresh morning?” she asked, “I love this time of day best of all.” And again I fumbled for words.

We spoke a few more moments. Then she moved on around the corner to continue her walk and I retreated to my room to curse myself for my lack of grace.

In general, the weekend was quiet. Mr Spenlow and I spent time reading in his library. All of our meals and teatimes we shared with Dora and by our return on Sunday evening. I had got myself enough in shape to be making intelligent conversation. Neither my host nor his daughter had any idea that I was hopelessly in love.

In the weeks after my time at Norwood, I found reasons to be out of the office, delivering papers or answering requests for meetings. And on rare occasions I saw Dora; several times we met by chance and talked. But I could never bring myself to tell her of my interest, let alone my slavish devotion. And I waited for another invitation to Mr Spenlow’s house—but none came.

I was in a rut, and decided to find other entertainment, so I called on Tommy Traddles. He lived on a little street near the Veterinary College at Camden Town. Something about the neighbourhood—its shabbiness, the tenants’ habit of tossing unwanted things into the street and leaving them to rust or rot, the noise—reminded me of the places I’d lived with the Micawbers. The man delivering milk was shouting at the housekeeper when I walked up on the porch.

“Now, what of that bill of mine? When will it be paid?”

“The master, he says he’ll pay it right away, he does, sir,” the young woman said. She was holding the pints of milk and packs of cheese tight in her arms.

“Do you like that milk you’re clutching there? Because it’s the last you’ll taste until the bill is paid up. You tell the master that, will you?” He rattled the empty bottles and stomped off to his wagon.

I stepped inside and was directed to a room at the top of the back stairs. Traddles was studying from a huge book, surrounded by even larger books and dictionaries on a table spilling over with papers.

We talked for a long time, recalling times at Salem House, catching up on where we’d been and what we’d done since. He told me of his studying for the bar examination, of his friends, and of his engagement to a minister’s daughter.

“I’m saving every cent for the time we marry,” he laughed, “because she’s one of ten children and life is likely to be expensive. That’s why I’m boarding here with the Micawbers. They have seen a good deal of life and are excellent company.”

“Who?” I exclaimed, “Who are your landlords?”

“The Micawbers. Fine people, although he seems unable to get a handle on a good job right now. There luck’s a little thin.”

When I told Traddles how I knew the Micawbers, he insisted on running downstairs and asking them to join us.

“Good heavens, Traddles,” cried Mr Micawber as he pumped my arm with all his might, “to think that you should know my favourite boy, Copperfield It’s a small world, indeed.”

We had more catching up to do. More news of Micawber’s endless waiting for something to turn up and the money-losing schemes he concocted in the meantime. More words of support from his long-suffering wife. The evening was dark and the fire all but burned out when I rose to leave.

The next evening my landlady brought word that a very handsome and well-dressed man was waiting for me in the parlour. Steerforth, I thought at once.

“Can it be, Davy, that I’ve caught you in?” he cried. “I expected the busy young lawyer to be out playing the fool with any of a cast of young women. Are you only taking an evening’s rest? Why, you Doctors’ Commons fellows are the most social men in London.”

“We’re a wild crowd, James!” I laughed at the thought, “if you consider green eyeshades and suspenders partywear. And so how is life at Oxford—all somber study, I’m sure.”

“Don’t know that,” he said, “I’ve been in Yarmouth the last couple weeks, checking on my boat and generally having a good time. The Little Em’ly is quite a nice bit of work.”

“How is everyone there? Is Em’ly married yet?”

“Not yet. Probably will be soon, though.” He picked up his coat and slid a hand into the inside pocket. “I’ve got a letter for you, from your friend Peggotty. Old what’s his name’s in a bad way.”

“Do you mean Barkis?” I made my way through Peggotty’s curly, wavy-lined script and folded the letter again.

“It’s tough,” Steerforth said as he pulled on his coat and scarf, “but the sun sets every day and people die every minute. We can’t be frightened by someone else’s death. No. Ride on over all obstacles and win the race at any price. That’s the lesson for me.”

I put on my coat and walked with him to the end of the lane. We said good night and he turned away towards the carriage stand, then stopped and came back. He stood a moment, studying the gloves he held in his left hand, then looked at me.

“Davy, if anything should ever separate us, you have to think of me at my best. Let’s make that a deal. Think of me at my best, if circumstances ever part us.”

He turned away again, and with long strides he was around the corner in a moment. Watching him go, I thought of his saying, “Ride on over all obstacles and win the race!” and I wished, for the first time, that he had some race worth running.